1. How Fractions Denote Pitches

In the notation of just-intonation (pure) tuning, pitches are given as fractions, which are actually ratios between the named pitch and a constant fundamental. For example, if C is the reference pitch (if we're in the "key of C"), then

C

is denoted as

1/1.Any C in the scale can then be denoted as 1/1. Or, the C an octave above a particular C can be denoted as 2/1, since a 2-to-1 ratio between frequencies is an octave.

In order to define pitches by fractions, some arbitrary pitch needs to be defined as 1/1. E-flat can be 1/1, or F-sharp, or A-flat - it doesn't matter. For now, we'll use 1/1 = C.

These ratios are always ratios between the rate of vibration of two tones. For example,

if one pitch vibrates at 200 cycles per second,

and another pitch vibrates at 400 cycles per second,

then the two pitches make an octave, the most basic of musical intervals.

We can call the first, lower pitch 1/1, and the second, higher pitch 2/1.(An interval is simply the distance between any two pitches in perceived pitch-space.)

The confusing thing for most people is that fractions denoting octaves are equivalent. That is, 1/1 is the same pitch as 2/1, and also the same pitch as 4/1. We're used to eight different keys on the piano all being called by the same letter - C - but we're not used to fractions behaving this way: 1/1 = 2/1 = 4/1. In just intonation, that's the way it is. Fractions in tuning are usually written in such a way as to bring them between 1/1 and 2/1, multiplying or dividing by 2 when necessary. That is,

the fractions 3/4 and 7/2

will usually be written as

3/2 and 7/4,

because those fractions are equivalent by multiplication by 2,

and the latter pair are between 1/1 and 2/1.For many people, this is the hardest aspect of tuning theory: getting used to the idea that

5/12 = 5/6 = 5/3 = 10/3 = 20/3 If one pitch vibrates at 200 cycles per second and another at 300 cycles per second, we have a 3/2 ratio. This is what musicians commonly call a "perfect fifth": C to G. If we are in the key of C, then

1/1 denotes C,

and

3/2 denotes G.The ratio 3/2 simply means that one pitch vibrates 3/2 as fast (three halves as fast) as the other.

The fraction or ratio 5/4 gives us what musicians call a "major third," that is, E in the key of C. (The E string vibrates 5/4 as fast as the C string.) Notes that have these simple arithmetical relationships sound good (consonant) together; the ear registers their harmoniousness. ("Harmony" and "arithmetic" are derived from the same root.) Ever since Ptolemy in the second century A.D., our major scale has been an approximation of the following ratios:

C D E F G A B C 1/1 9/8 5/4 4/3 3/2 5/3 15/8 2/1

Listen to the scale:Whenever you sing "Way down upon the Swanee River" - E D C E D C C' A C' - your voice and ear are unconsciously measuring these ratios to the tonic pitch: 5/4, 9/8, 1/1, 5/4, 9/8, 1/1, 2/1, 5/3, 2/1, and so on. Didn't know your ear could calculate exact ratios between frequencies, did you? It can, with astonishing accuracy.

Naturally, there are an infinite number of fractions, and every single fraction between 1/1 and 2/1 pinpoints a potential note in a scale. For example, we could expand Ptolemy's scale above to complete a chromatic scale of 12 pitches:

C C# D Eb E F F# G Ab A Bb B C 1/1 16/15 9/8 6/5 5/4 4/3 45/32 3/2 8/5 5/3 9/5 15/8 2/1 Although 12 is something of a natural limit for the number of pitches in an octave, it is by no means sacrosanct. A virtual infinity of other pitches is possible, and many are in common use in non-Western musics (and increasingly, in American music as well), such as 9/7, 21/16, 7/6, 7/4, 11/8, 243/128, and so on and so on and so on. In 1588, in an attempt to have a wide range of chords perfectly in tune, Gioseffo Zarlino designed a harpischord on the following model, with 16 pitches per octave:

C C# D- D Eb- Eb E F F#- F# G G# A Bb- Bb B C 1/1 25/24 10/9 9/8 32/27 6/5 5/4 4/3 25/18 45/32 3/2 25/16 5/3 16/9 9/5 15/8 2/1

Listen to the scale:This is somewhat similar in concept to my own tuning for my synthesizer piece Fractured Paradise. It has been the intention of many recent composers, my teacher Ben Johnston included, to pick up tuning experimentation again at the point it was dropped around 1600. Johnston's notation of microtones begins with the 16th-century Italian definitions of intervals and continues from there.

2. How to Play with Intervals

How can we tell what kind of interval a fraction designates?

Scientists have devised a standard unit for measuring the size of perceived intervals resulting from two frequencies vibrating at a given ratio. This unit is called a cent because it equals 1/100th of a half-step. A half-step is the smallest interval between two notes on the piano. There are 12 half-steps in an octave, and so one octave = 1200 cents. By definition.

This means that all of our normal intervals on the modern piano are divisible by 100 cents. For example, what musicians call a

half-step (C up to Db) = 100 cents

whole step (C to D) = 200 cents

minor third (C to Eb) = 300 cents

major third (C to E) = 400 cents

perfect fourth (C to F) = 500 cents

augmented fourth (diminished fifth, C to F#) = 600 cents

perfect fifth (C to G) = 700 cents

minor sixth (C to Ab) = 800 centsYou can figure out the rest.

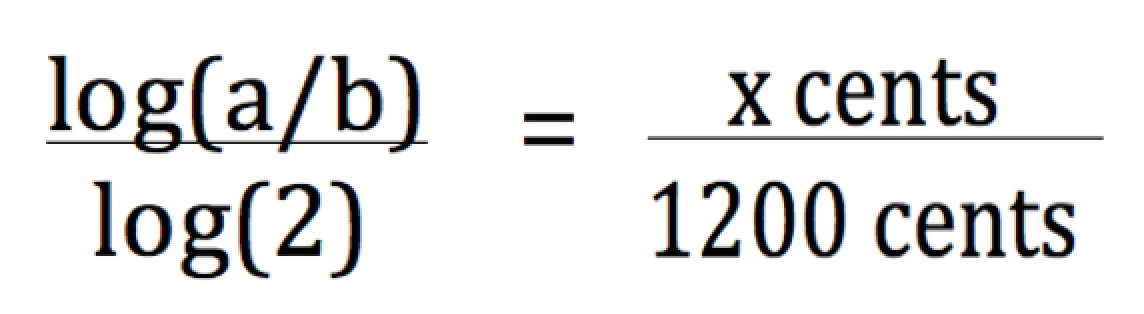

There is a slightly complicated formula for figuring out how many cents large an interval is. The number of cents in the interval has the same proportion to 1200 as the ratio's logarithm has to the logarithm of 2:

You can, then, multiply each side of this equation by 1200 to find X: log(a/b)/log(2) x 1200 = X. Or the way I do it on a daily basis is:

Divide 1200 by the logarithm of 2.

If you use base 10 logarithms (any base is permitted), 1200/log 2 = 3986.3137...For any ratio a/b,

the number of cents in the interval islog (a/b) x 1200/log 2

If you're using log 10, then

cents = log (a/b) x 3986.3137...

I store 3986.3137... as a constant on my calculator, to cut out a couple of steps. Using this formula, we can obtain the following interval sizes:

16/15 = 111.73... cents

9/8 = 203.91 cents

8/7 = 231.17... cents

7/6 = 266.87... cents

6/5 = 315.64... cents

11/9 = 347.4... cents

5/4 = 386.31... cents

9/7 = 435.08... cents

1323/1024 = 443.52... cents

21/16 = 470.78... cents

4/3 = 498 cents

7/5 = 582.51... cents

3/2 = 702 centsAnd so on, and so on. (Find a reference chart of several hundred intervals within an octave, given with ratios and cents, at Anatomy of an Octave.)

The smaller the numbers in an interval's ratio, the more consonant (sweet-sounding) it is, and the more useful it is for purposes of musical intelligibility. (There are times, of course, when unintelligibility is desirable.) The most consonant interval besides the unison (1/1) is the octave (2/1), next the perfect fifth (3/2), then the perfect fourth (4/3 - even though European music long treated this interval as a dissonance), then the major sixth (5/3), then the major third (5/4), minor third (6/5), and so on. (6/4, of course, reduces to 3/2.)

Using slightly larger numbers, we get a variety of interval sizes among pitches whose ratios are still simple enough to learn to hear. For instance, here is a series of major seconds, ranging from one a quarter-tone flat to one a sixth-tone sharp:

Ratio: 11/10 10/9 9/8 8/7 Cents: 165 182 204 231 Likewise, there are several simple thirds, ranging from a bitterly narrow 7/6 minor third to a "normal" 6/5 minor third to an "undecimal" (11-related) "neutral" third (in-between major and minor) of 11/9, to a normal major third of 5/4, to a wide 9/7 major third:

Ratio: 7/6 6/5 11/9 5/4 9/7 Cents: 267 316 347 386 435 Notice that the two 7-related thirds, 7/6 and 9/7, are at 267 cents and 435 cents - each of them about a third of a half-step away from 12-pitch equal temperament. This means that dividing your octave into 36 equal steps will accommodate a lot of 7-related intervals. Also notice that the 11-related intervals, like 11/10 and 11/9, are very close to quarter-tones. A quarter-tone scale allows for close approximations of a lot of 11-related intervals.

Here is a sequence of fourths leading into tritones and then fifths, actually the same sequence I use as drones in the Battle Scene of Custer and Sitting Bull:

Ratio: 21/16 4/3 27/20 11/8 7/5 10/7 16/11 40/27 3/2 Cents: 470.8 498.0 519.6 551.3 582.5 617.5 648.7 680.5 702.0 By the way, it's really not so difficult to learn to recognize these intervals by ear. When I first started out with this in 1984, I would tune a synthesizer to the intervals I wanted to learn - I started out contrasting 10/9 and 9/8 - and then let the intervals run in a loop on tape (later computer-sequenced) as I was going about my daily business, letting myself pick up the differences in character with my peripheral hearing. Today, if I'm composing in just intonation and I accidentally use a pitch as much as five cents off from the one I wanted, I catch the mistake by ear almost immediately - because I recognize that the character of the interval is not the one I wanted. (And no, I don't have perfect pitch.)

So what about the larger numbers, like 1323/1024 and 243/128? Why do such intervals exist at all?

Usually because they are derived intervals that are useful for modulating to different tonics, or transposing chords. I'll explain in a roundabout way:

Another of the biggest mental blocks for people starting out with tuning theory is that, to add two intervals together, you have to multiply their ratios. For example,

a major third (5/4) plus a minor third (6/5)

does not equal

5/4 + 6/5 (which would be 49/20)a major third (5/4) plus a minor third (6/5)

equals

5/4 x 6/5 = 6/4 = 3/2,

which is a perfect fifth.a major third plus a major third equals

5/4 x 5/4,

which equals

25/16 - an augmented fifth of 772.63... centsIn just intonation, an augmented fifth is a different interval from a minor sixth. A minor sixth is

a perfect fourth plus a minor third, or

4/3 x 6/5,

which equals 24/15 = 8/5:

a minor sixth of 813.69... cents.Here's a demonstration of how different 25/16 is from 8/5:

So, for some musical purposes, we might want a pure minor seventh of

7/4

And above that 7/4 we might want to have a perfect fifth available:

7/4 x 3/2 = 21/8 = 21/16

Remember, we want to multiply or divide by 2 when necessary to get our fraction between 1/1 and 2/1. And above that 21/16, we might want a whole step:

7/4 x 3/2 x 9/8 = 189/64 = 189/128

That's a simple harmonic structure, but already the numbers are getting pretty big. And the most complex number in La Monte Young's The Well-Tuned Piano, 1323/1024, is the result of taking a minor seventh

7/4

and the going up another minor seventh

7/4 x 7/4 = 49/16 = 49/32

and then going up a perfect fifth

7/4 x 7/4 x 3/2 = 147/32 = 147/128

and then going up two more perfect fifths

7/4 x 7/4 x 3/2 x 3/2 x 3/2 = 1323/128 = 1323/1024

That's not a very complicated musical relationship for a composer to think in, but the numbers get complicated if you're trying to think of it in just intonation. And actually, that pitch is the least often used in The Well-Tuned Piano, and doesn't appear on the recorded version at all.

3. Why Is This Different from Our Normal Tuning?

You've probably noticed that, while the intervals on our modern piano are all divisible by 100 cents - 200 cents, 300, 400.... - none of the above intervals is divisible by 100. Two of them are close: 4/3 (498 cents) and 3/2 (702 cents) are very close to 500 and 700, which are divisible by 100. 9/8 (204 cents) is almost as close.

Our modern system of tuning, called equal temperament, is a compromise. We divide the octave into 12 equal intervals not because it sound better that way - it doesn't at all, it's slightly buzzy with audible beating between sustained pitches - but so we can transpose any music to any key. To see why just intonation makes transposition and modulation difficult (at least within the confines of a 12-pitch keyboard), let's look again at Ptolemy's major scale, with each note's cents-distance from the tonic filled in (rounded off to the nearest cent):

Pitch: C D E F G A B C Ratio: 1/1 9/8 5/4 4/3 3/2 5/3 15/8 2/1 Cents: 0 204 386 498 702 884 1088 1200 You can play this scale here:

That's a fine scale for playing in the key of C. The major third above C is 386 cents, the perfect fifth is 702 cents - it'll sound great. But let's move to the key of D and recalculate the intervals in cents above D:

Pitch: C D E F G A B C Ratio to C: 1/1 9/8 5/4 4/3 3/2 5/3 15/8 2/1 Ratio to D: 8/9 1/1 10/9 32/27 4/3 40/27 5/3 16/9 Cents: -204 0 182 294 498 680 884 996 You can play this scale, from D to D, here:

The perfect fifth from D to A is now only 680 cents wide instead of an optimum 702, and it sounds awful. You may have noticed it has a wow-wow-wow growl to it, which you can hear in isolation here: , that explains why such fifths have always been called "wolf" intervals. (Here: you can hear it contrasted with a simpler 3/2 fifth.) You might occasionally want that sound for a scary moment, but you generally can't use it as a point of stability. In addition, the D-to-F interval is 32/27 (294 cents) instead of an optimum 6/5 (316 cents), so that minor third will sound a little pinched and harsh as well. A keyboard tuned perfectly to C like this will sound lovely as long as you don't venture beyond the I, IV, and V chords of C (C, F, and G major triads), but the minute you try a ii chord (D) you're in trouble, as you can hear in the twangy fifth chord of this chord progression: (which would sound even worse on an acoustic piano). And as for playing in more distant keys like A-flat and E major and F# - forget it.

So we compromise. We jiggle all of the pitches around until all the perfect fifths are equal, all 700 cents, which after all is pretty close to 702. All the major thirds, though, are 400 cents instead of 386, which is pretty sharp. We don't notice how bad our major thirds sound because our culture has been awash in equal-tempered intervals since the turn of the last century. We grow up desensitized to the buzz that equal-tempered intervals make, a buzz you can hear quite clearly by sitting at a piano and playing two low-register notes an octave and a major third apart, or a major sixth apart. (Those are particularly obvious examples. In fact, piano tuners count the beats per second in those intervals to tell when they've tuned a piano "correctly.")

Many recent composers have come to feel that the compromise of equal temperament was a mistake. They feel that the musical logic of moving from any key to any other key became a priority at the expense of music's sonic sensuousness. Harry Partch was the first such composer. He defined his own scale with 43 pitches to the octave, and invented his own instruments to play it. Lou Harrison was the next major figure to abandon equal temperament; he has used many tunings taken from Indonesian gamelans, and also, in his Piano Concerto, returned to an almost-pure tuning called Kirnberger II from the 18th century. Other composers to work in pure tuning (just intonation) include Partch's protege Ben Johnston (my teacher), La Monte Young, Terry Riley, Pauline Oliveros, James Tenney, Rhys Chatham, Glenn Branca (in his middle symphonies, Nos. 3, 4, and 5), Ben Neill, Dean Drummond, and myself (Kyle Gann).

4. What Does Music in Pure Intervals Sound Like?

One of the most exotic scales any major piece of music has ever been based on is that of La Monte Young's The Well-Tuned Piano, given here:

Notes: Eb E F F# G G# A Bb B C C# D Ratios: 1/1 567/512 9/8 147/128 21/16 1323/1024 189/128 3/2 49/32 7/4 441/256 63/32 Cents: 0 177 204 240 471 444 675 702 738 969 942 1173

Listen to the scale here:Here is a quiet, transitional excerpt from the piece that uses a variety of the intervals offered.

Here's an excerpt, the first minute, from Ben Johnston's Suite for Microtonal Piano (1977): in which the piano is entirely tuned to overtones of C. You can clearly hear the 11th harmonic halfway between F and F#, and the 31-cent "flat" seventh harmonic. The scale is as follows:

Notes: C C# D Eb E F F# G Ab A Bb B Ratios: 1/1 17/16 9/8 19/16 5/4 21/16 11/8 3/2 13/8 27/16 7/4 15/8 Cents: 0 105 203.9 297.5 386.3 470.8 551.3 702 840.5 905.9 968.8 1088.3 Here's an excerpt from the final scene of my Custer and Sitting Bull: based on a 31-pitch scale over a G drone. Voice-leading in tiny increments, especially in the part of the scale from A up to D, is clearly audible.

I've had interesting experiences playing just-intonation music for non-music-major students. Sometimes they will identify an equal-tempered chord as "happy, upbeat," and the same chord in just intonation as "sad, gloomy." Of course, this is the first time they've ever heard anything but equal temperament, and they're far more familiar with the first sound than the second. But I think they correctly hit on the point that equal temperament chords do have a kind of active buzz to them, a level of harmonic excitement and intensity. By contrast, just-intonation chords are much calmer, more passive; you literally have to slow down to listen to them. (As Terry Riley says, Western music is fast because it's not in tune.) It makes sense that American teenagers would identify tranquil, purely consonant harmony as moody and depressing. Listening from the other side, I've learned to hear equal temperament music as a kind of aural caffeine, overly busy and nervous-making. If you're used to getting that kind of buzz from music, you feel the lack of it as a deprivation when it's not there. But do we need it? Most cultures use music for meditation, and ours may be the only culture that doesn't. With our tuning, we can't.

My teacher, Ben Johnston, was convinced that our tuning is responsible for much of our cultural psychology, the fact that we are so geared toward progress and action and violence and so little attuned to introspection, contentment, and acquiesence. Equal temperament could be described as the musical equivalent to eating a lot of red meat and processed sugars and watching violent action films. The music doesn't turn your attention inward, it makes you want to go out and work off your nervous energy on something.

On a more subtle level, after I've been immersed in just intonation for a couple of weeks, equal temperament music begins to sound insipid, bland, colorless. There are only eleven types of intervals available instead of the potential several dozen that exist in even the simplest just system, and you don't get gradations of different sizes of major third or major sixths the way you do in just tuning. On a piano in just intonation, moving from one tonic to another changes the whole interval makeup of the key, and you get a really specific, visceral feel for where you are on the pitch map. That feeling disappears in bland, all-keys-the-same equal temperament. As a composer, I enjoy having the option, if I'm going to use a minor third interval, of being able to choose among the 7/6, 6/5, 19/16, and 11/9 varieties, each with its own individual feeling.

Far beyond the mere theoretical purity, playing in just intonation for long periods sensitizes me to a myriad colors, and coming back to the equal tempered world is like seeing everything click back into black and white. It's a disappointing readjustment. Come to think of it, maybe you shouldn't try just intonation - you'll become unfit to live in the West, and have to move to India or Bali.

Does this sound like I have a problem with European music? I don't at all. My complaint is with the bland way in which European and American musics are currently tuned. In fact, before the 20th century, European music had its own wonderful non-equal-tempered tunings, which unfortunately we've abandoned. To read about them, go to my Introduction to Historical Tunings page.

In a moment, as promised, some recordings of just-intonation works. But first, some

Tuning Charts for Kyle Gann's music: Hyperchromatica

Solitaire

Cinderella's Bad Magic

Triskaidekaphonia (Tuning Study No. 6)

Charing Cross (Tuning Study No. 8)

New Aunts (Tuning Study No. 9)

The Day Revisited

Love Scene for string quartet

Custer: "If I Were an Indian..."

Sitting Bull: "Do You Know Who I Am?"

Sun Dance / Battle of the Greasy Grass River

Custer's Ghost to Sitting Bull

How Miraculous Things Happen (Tuning Study No. 4)

Fugitive Objects (Tuning Study No. 7)

Fractured Paradise (Tuning Study No. 3)

Superparticular Woman (Tuning Study No. 1)

Ghost Town

Arcana XVI (Tuning Study No. 5)Hear audio samples of some of these just intonation works.

Selected Just Intonation Discography La Monte Young: The Well-Tuned Piano - Young, piano; Gramavision, 18-8701-2 (five CDs).

La Monte Young: Just Stompin' (Young's Dorian Blues in G) - Forever Bad Blues Band; Gramavision R2 79487

Terry Riley: The Harp of New Albion - Riley, piano; Celestial Harmonies CEL 018/19 (two CDs).

Terry Riley: Shri Camel (Anthem of the Trinity; Celestial Valley; Across the Lake of the Ancient Word; Desert of Ice) - Riley, just-intonation organ; CBS MK 35164.

Ben Johnston: Suite for Microtonal Piano, Sonata for Microtonal Piano, Saint Joan - Phillip Bush, piano; Koch International Classics 3-7369-2-H1.

Ben Johnston: String Quartets Nos. 2, 3, 4, & 9 - Kepler String Quartet; New World 80637-2.

Ben Johnston: String Quartets Nos. 1, 5, & 10 - Kepler String Quartet; New World 80693-2.

Ben Johnston: String Quartets Nos. 6, 7, & 8 - Kepler String Quartet; New World 80730-2.

Ben Johnston: Suite for Microtonal Piano - Robert Miller, piano; New World Records, 80203-2.

Toby Twining: Chrysalid Requiem - Toby Twining Music; Cantaloupe CA 21007

Kyle Gann: Hyperchromatica, Other Minds OM 1025-2

Kyle Gann: Custer and Sitting Bull - New World Records 80801.

Kyle Gann: The Day Revisited on Private Dances, New Albion NA 137

Kyle Gann: Ghost Town - New Tone nt 6730.

Michael Harrison: From Ancient Worlds - Harrison, piano; New Albion NA o42 CD.

Michael Harrison: Revelation - Harrison, piano; Michael Harrison Music MHM 101

Ben Neill: Green Machine - Neill, trumpet (with computer electronics); Astralwerks asw 6159-2.

David B. Doty: Uncommon Practice - Syntonic SN63:32.

Brian McLaren: Undiscovered Worlds - MRS CD 029.

Brian McLaren: Music from the Edge, Volume 2 - MRS CD 017.

Copyright 1997 by Kyle Gann

Return to the La Monte Young Web Page

If you find any of this not clearly enough expressed, e-mail me.