George Rochberg: Symphony No. 2 (1955-56)

Analysis by Kyle Gann

All score reductions by the author

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 3.0 License.When I have taught twelve-tone music, I have commonly had the experience that the students sit stolid and unimpressed through examples by Schoenberg, Webern, and Berg - until I play Rochberg's Second Symphony, which occasions the first classroom-wide outburst of enthusiasm. It is indeed a more powerfully physical work than the idiom habitually produced. I have always thought that George Rochberg (1918-2005) was America's best twelve-tone composer before he abandoned the idiom, and this, perhaps his most ambitious twelve-tone piece, is no less impressive for its tight narrative arc than its propulsive momentum.

Rochberg's eventual rejection of twelve-tone technique and embrace of stylistic heterogeneity sparked surprising rancor in academic circles, and despite his stature he seemed to have become persona non grata, resented more as an apostate than he would have been as an original non-believer. It may be because of that that his subsequent symphonies have been rather shamefully neglected, especially considering that the Third (1966-69), Fourth (1976), and Fifth (1984) document his radical turn toward style quotation and actual quotation, his plunge back into Romanticism, and his partial return toward abstraction. But his trajectory has always struck me as a heroic risk. "We are not slaves of history," he wrote. "We can choose and create our own time."

Having received the idiom from Dallapiccola, who did not adhere to it strictly, Rochberg took even more freedom with it, and this piece has had a daunting reputation for being difficult to analyze. I am indebted to a 2007 doctoral dissertation by Yoojin Kim, "An Innovative Approach to Serialism: George Rochberg's Twelve Bagatelles for Piano and Symphony No. 2," for speeding my entree into the work. I have retained most of Kim's sectional divisions and some of his theme designations, though not his row numbering.

First movement -- mm. 1-255

Exposition -- mm. 1-122

First thematic area -- mm. 1-61

Introduction -- mm. 1-4

First theme (A) -- mm. 4-18

Second theme (B) -- mm. 17-33

Theme A -- mm. 32-45

Themes A + B -- mm. 45-61

Second thematic area -- -mm. 62-122

Theme C -- mm. 62-66

Theme D -- mm. 67-76

Theme E -- mm. 76-87

Theme D -- mm. 88-89

Theme F -- mm. 90-94

Transition -- mm. 94-103

Themes C and D -- mm. 104-116

Theme C -- mm. 117-122

Development -- mm. 123-205

Wedge motive -- mm. 123-140

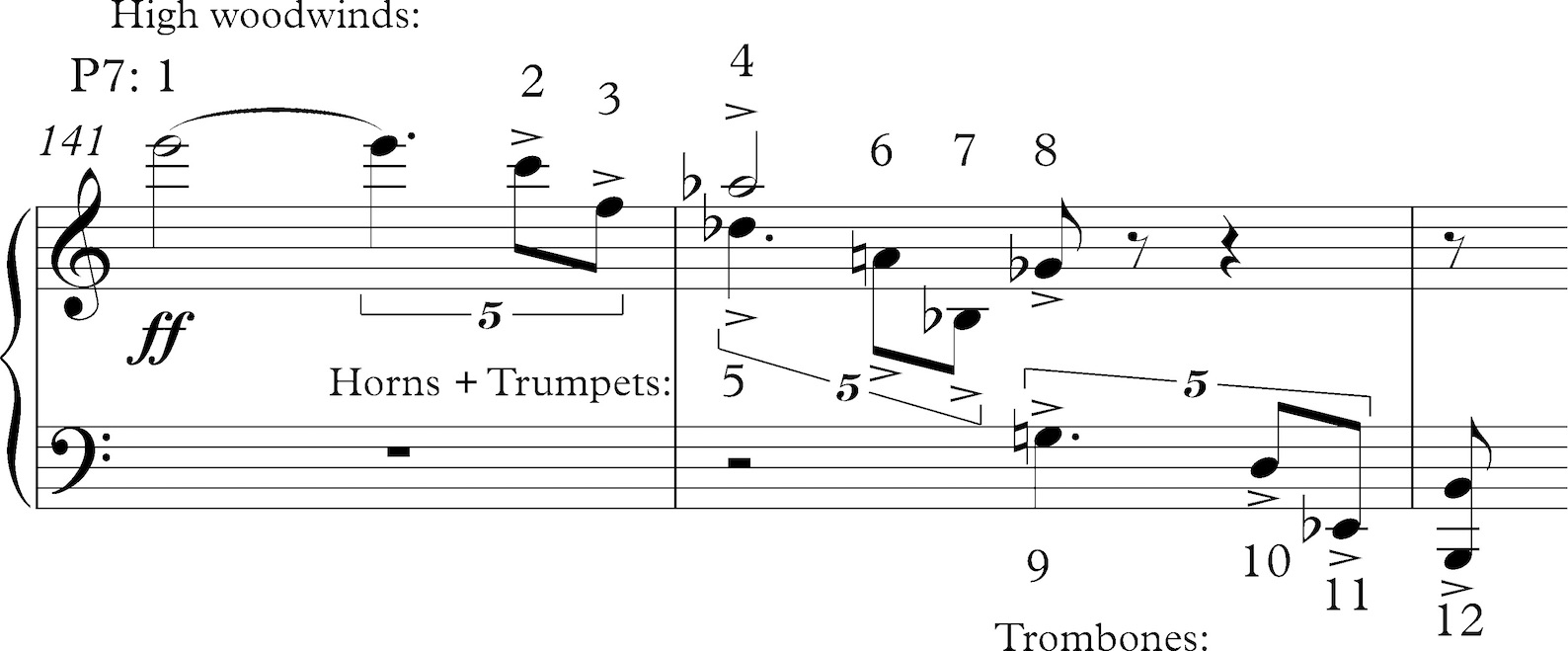

Various row segments -- mm. 141-154

Theme F -- mm. 155-166

Theme E -- mm. 167-184

Wedge motive -- mm. 185-202

Transition -- mm. 202-205

Recapitulation -- mm. 206-255

Intro and Theme B -- mm. 206-221

Themes A + B -- mm. 221-249

Twelve-pitch chord -- mm. 239-248

Transition -- mm. 249-255The symphony opens with a stunning and forceful gesture, surely the first orchestral tutti unison statement employing quintuplets.

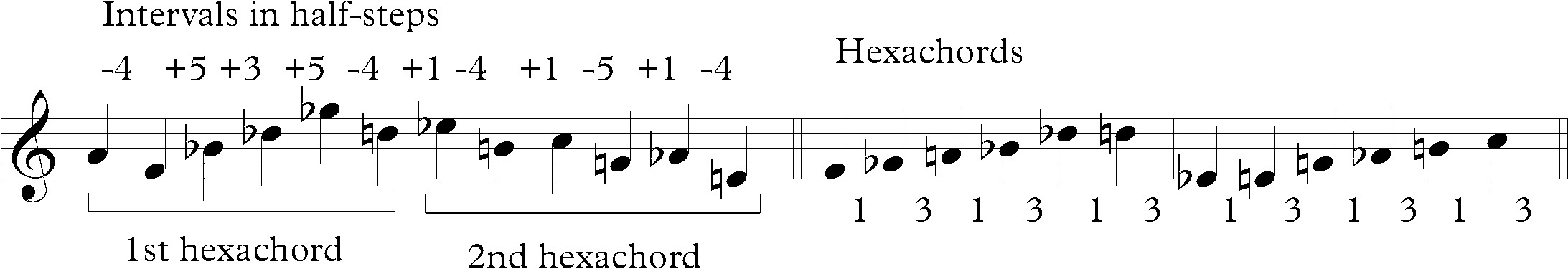

This is of course a twelve-tone row, the one on which the piece is based, though this is not a strict twelve-tone piece; Rochberg exercises considerable latitude in note order in his melodies and extra dissonance in his chords. In general, the thematic elements follow the row (with pitch repetitions allowed), while the chords are more freely chosen from the available trichords and tetrachords. Still, to understand the piece we need to examine some of the particular qualities of its row. If we divide it into hexachords (six-note groupings), and reorder each half in scalar order, we find that each half has the same structure, a scale of alternating half-steps and minor thirds.

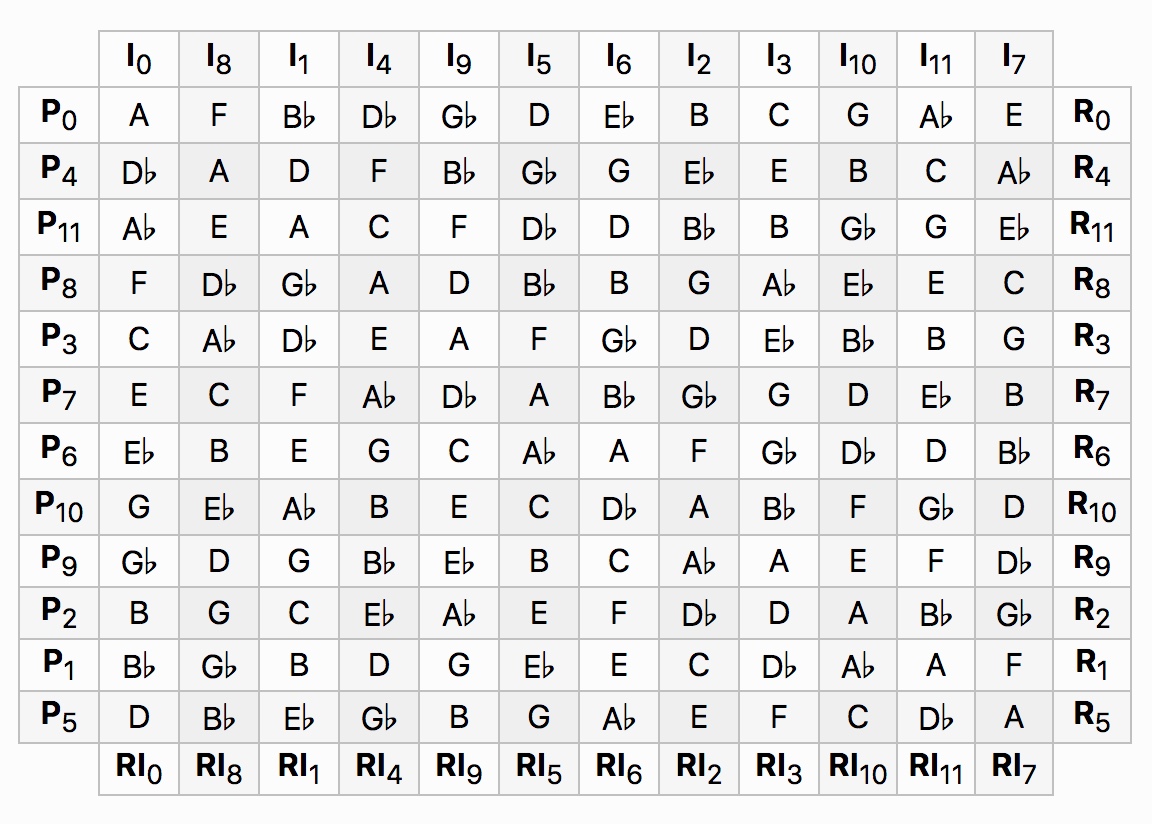

This hexachord is commonly called the augmented scale (and is used in jazz) because it consists of two augmented triads a half-step apart - also, doubtless, because it produces augmented seconds. It lends itself to major-minor vacillation, because in the form given above on F it contains both major and minor triads on F#, Bb, and D. The fact that the two halves of the row have the same interval structure, and that a symmetrically repetitive one, means that it will often be impossible to say definitively which form of the row a chord may come from - which is of course not important, except to the analyst who would like to feel he's come up with a definitive explanation. The matrix for this row is as follows.

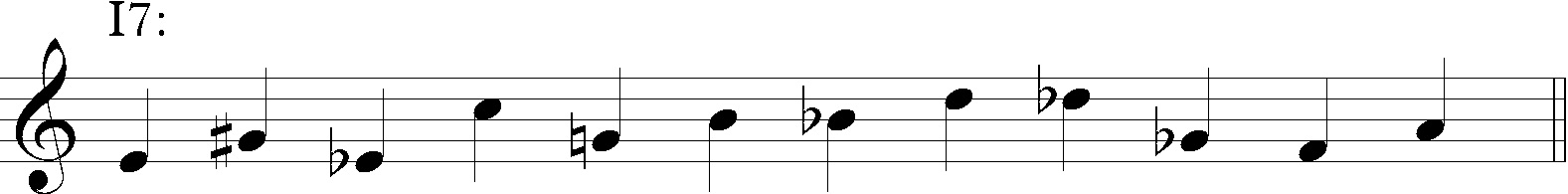

As it happens, the forms of the row most commonly foregrounded in the first movement are P0, the opening one we've seen, and I7, down the right-hand side, the inversion whose first note is P0's last note and whose last note is P0's first note - and Rochberg will overlap them.

Retrograde forms of the row will figure too, but sometimes Rochberg runs so freely back and forth through a row that the distinction between prime and retrograde ceases to be of much importance.

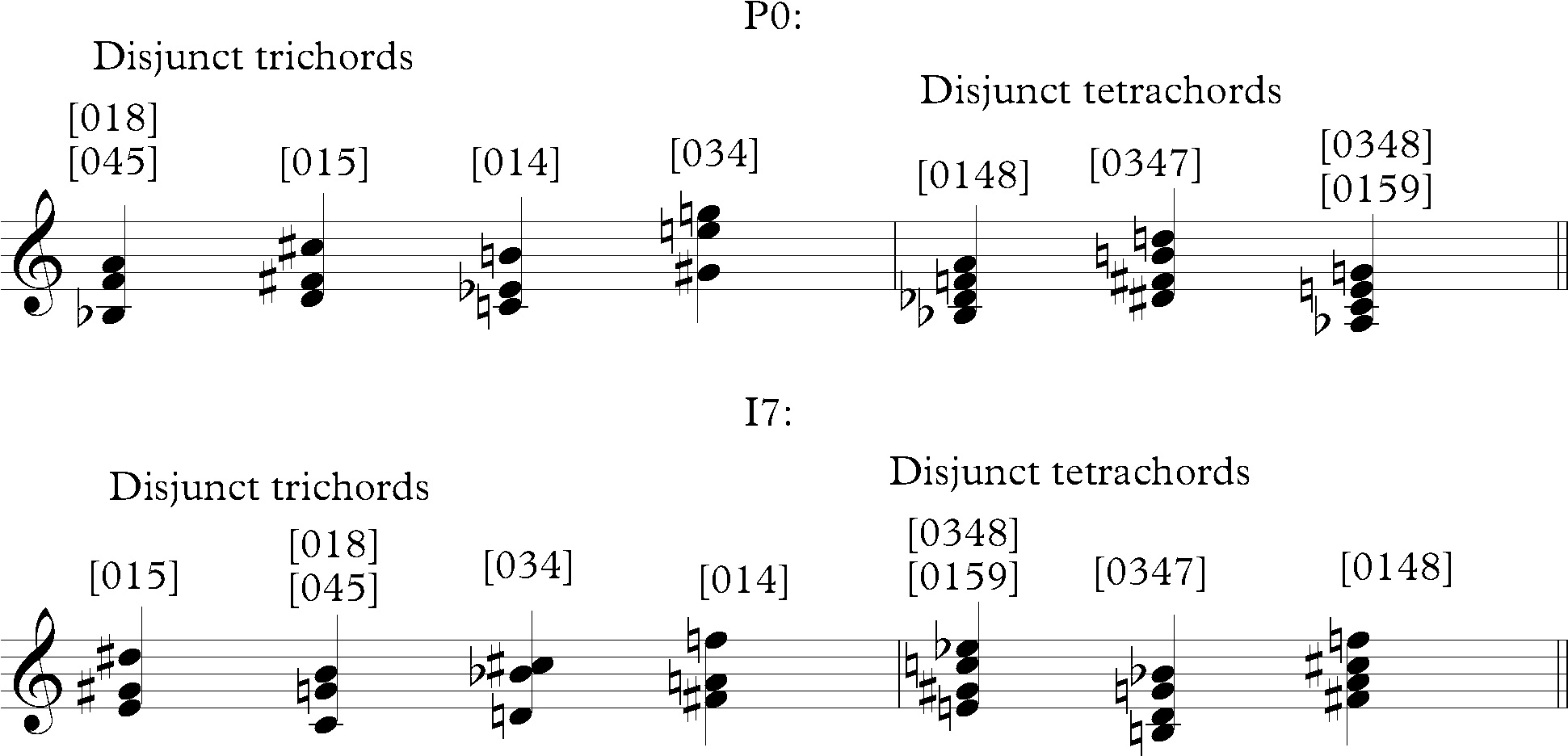

What will be important, aside from the hexachords, is the division of the row into trichords and tetrachords. I have labeled these with pitch set notation using the convention of taking the inversion that has the smallest numbers possible (although since it might be ambiguous whether one wants the lowest high number or the lowest small numbers, I've given double notations for some.)

These comprise the dominant (though not only) harmonic materials for the symphony. Notice that every trichord contains a major seventh/half-step, the other note being a minor or major third from one of the others; this is a result of using the augmented scale as source material. Major and minor triads are available among adjacent row notes, but these are exceedingly rare in the symphony. The tetrachords offer three types: a seventh chord with minor third and major seventh ([0148], much beloved of the early atonalists); a major/minor triad ([0347]); and an augmented seventh, an augmented triad with a major seventh. Also, the prime and inversion forms of the row give the same chords, in a different order, so if we can memorize these seven chord types, we will find them used ubiquitously in the symphony.

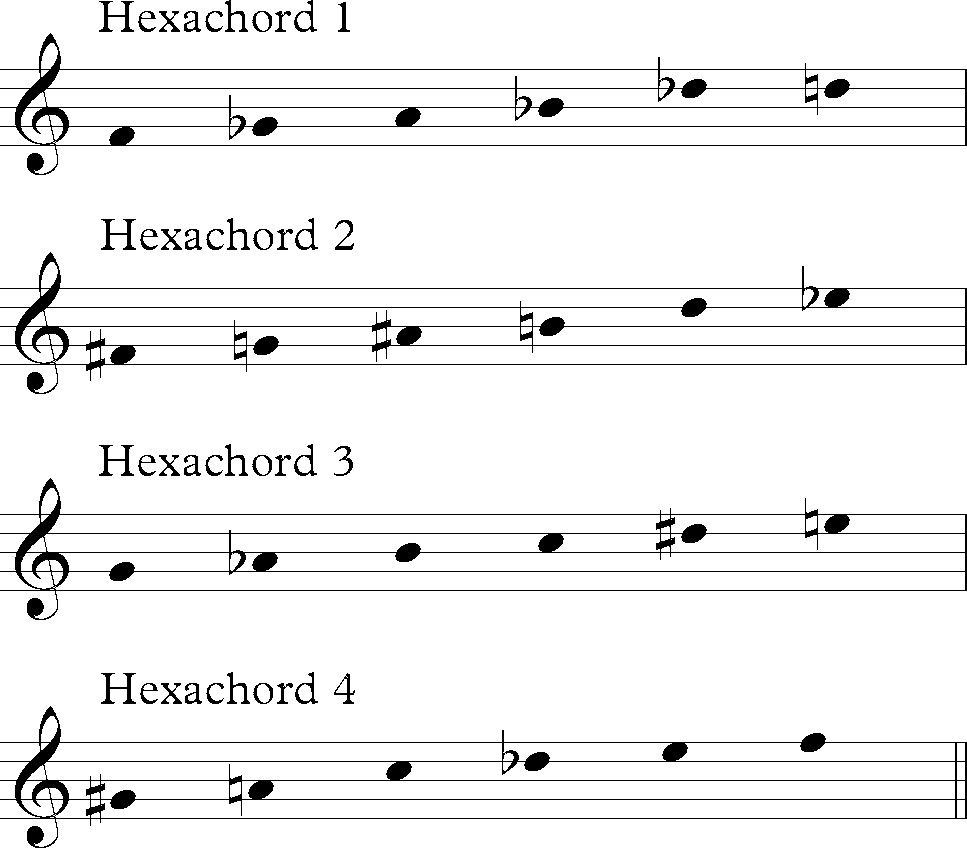

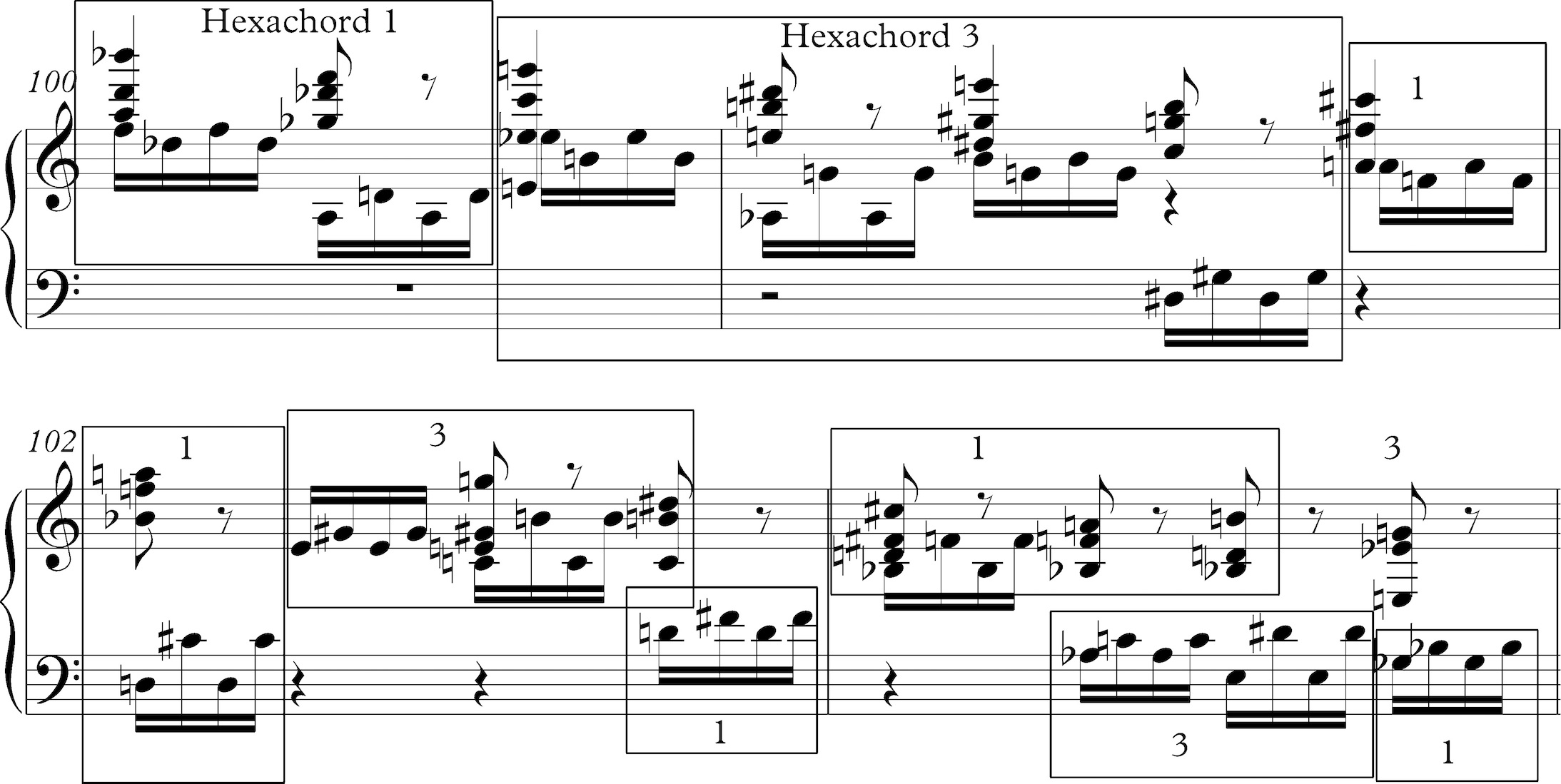

One last thing that will be useful is to number the four possible hexachords in the augmented scale. This scale is what Olivier Messiaen would have called a "mode of limited transformation" (though for some reason he doesn't include this one in his Technique de mon langage musical), meaning that if you transpose it by a certain interval - the major third in this case - it replicates its same pitch content. So starting with the symphony's opening hexachord I have labeled them 1 through 4. Note that hexachords 1 and 3 make up a twelve-tone row, as do 2 and 4, but 1 with 2 or 4 will duplicate three pitches, as will 3 with 2 or 4. Identifying the hexachord number of chords will help us find complementary row sets later.

Note that there are no major seconds nor tritones in the augmented scale. Any two notes separated by these intervals, then, are not in the same hexachord.

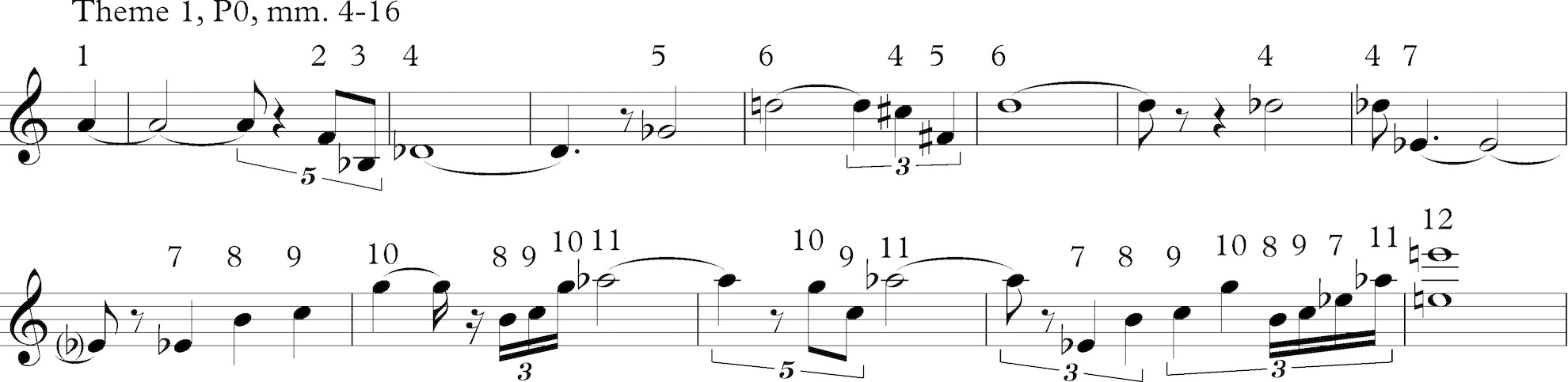

Now let's move to the main theme; there are only two primary themes, and they occupy the first 61 measures of the first movement, as well as 44 measures of the recapitulation and 33 of the last movement. The main theme follows the introductory motto and uses the same row, but as you can see from the pitch numbers I've added above each note, Rochberg is very free about going back to earlier pitches in the row, even leaping at m. 10 from pitch 4 (Db) to 7 (Eb) - though there is no minor seventh in the row.

This kind of freedom is certainly contrary to most twelve-tone usage, but it was practiced by Luigi Dallapiccola (1904-1975), whom Rochberg met in 1950 during a stay at the American Academy, and who sparked his interest in the idiom. In works like Piccola Musica Notturna (1954), Dallapiccola felt free to return to any pitch of the row that had already been introduced in that statement of the row. This gave him an ability to cycle through harmonies more slowly, obviating the twelve-tone idiom's greatest conceptual flaw: the fact that one tends to keep moving through the entire pitch spectrum at a regular pace. Rochberg was clearly impressed by the technique and took it farther than Dallapiccola did. In this symphony it gives his themes a broader arch and more memorability and dramatic power than is usual for twelve-tone music.

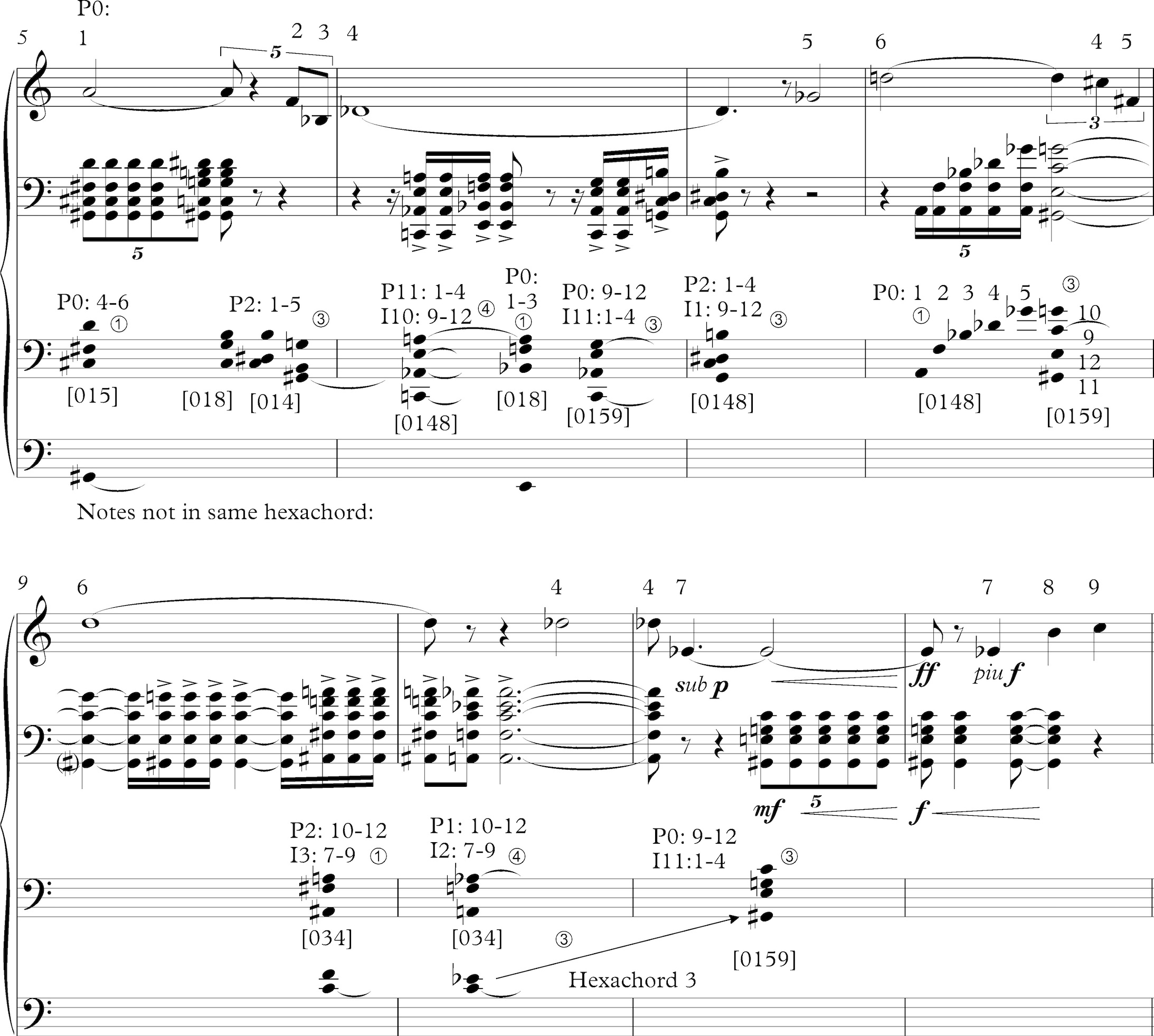

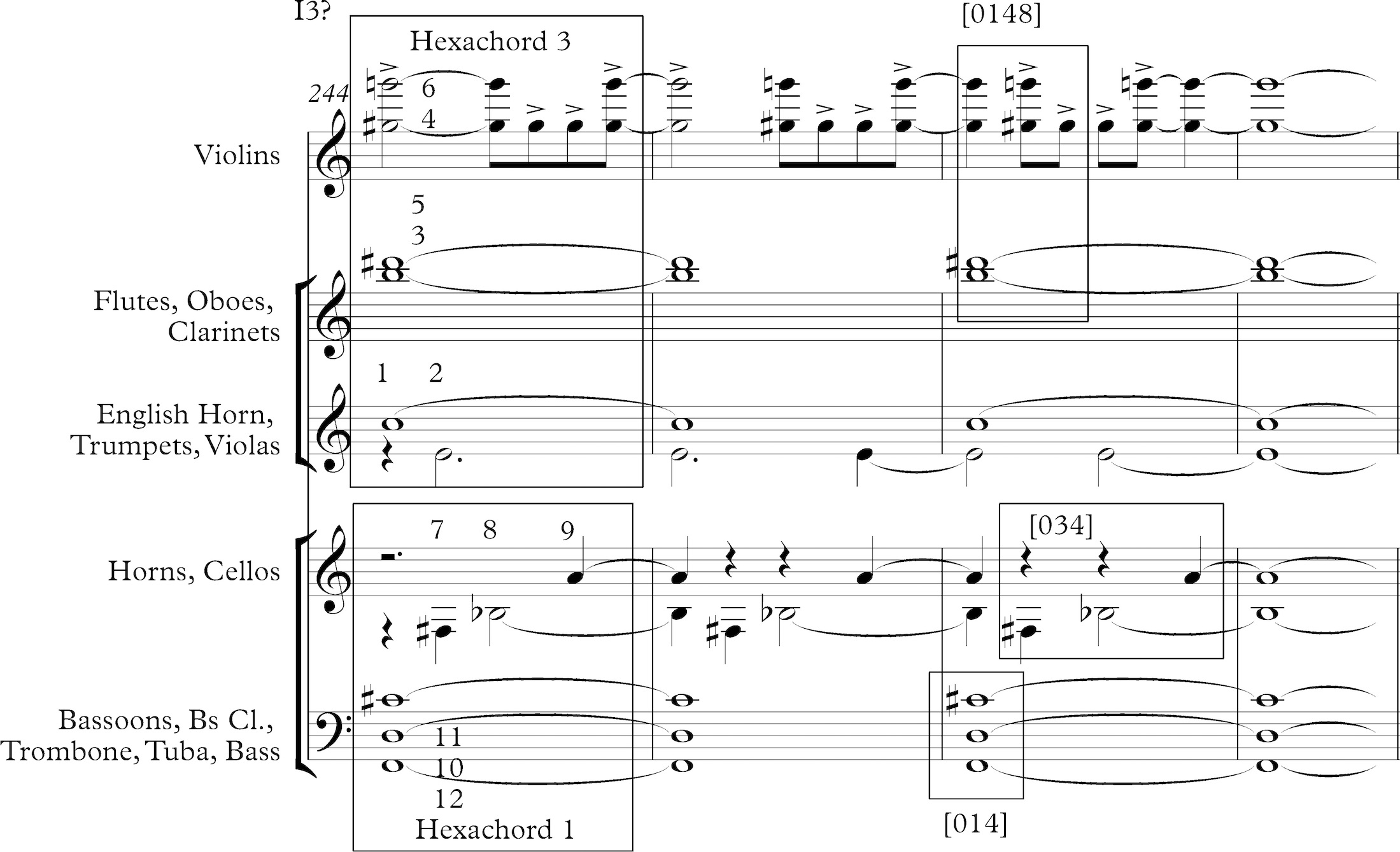

Before we proceed to the second theme, let's look at the harmony underlying this first theme statement. Beneath the chords in mm. 5-12 I have shown the relevant trichords and tetrachords on which the harmonies are based, and placed the notes that don't fit into the same hexachord on a bottom staff. All but one ([0347]) of the trichords and tetrachords above are included. I have also placed tie marks on the pitches that are retained from chord to chord. For instance, the G#/Ab remains nearly constant through mm. 5-6 and C from 8 to 12. Some of the chords could belong to more than one row, and there is no dominant row suggested, but P0, P1, and P2 are common. I have added numbers in circles indicating which of the four hexachords each chord is taken from. Note that in m. 8 Rochberg runs up through the first five pitches of P0 to land on a chord of the last four pitches.

The free writing this reveals shows how far Rochberg was willing to depart from the usual twelve-tone process in order to intensify his dissonances intuitively. Most of the piece, we will find, is not this resistant to analysis. Notice the rhythmic relation of these lines, such that one acts while the other is sustaining. This kind of back-and-forth was called "interpoint," as opposed to the simultaneously moving lines of counterpoint, by composer Alexander Tcherepnin (1899-1977), who used it frequently, though no one else seems to have taken up the term. It certainly imparts transparency to the texture and a dramatic relation between the sections of the orchestra in this symphony.

The second theme (which starts on the E with which theme one ends, and which will end on an A to start theme one again), is even more daring, spreading out one row across sixteen measures. I have marked with brackets two motives that will feature repeatedly in the movement. One is the E-D#-G#-E motive in m. 21 (let’s have fun and call it the edge motive), which involves pitches 1, 3, and 2, and which comes back at a different pitch level in mm. 27-28 with pitches 4, 6, and 1. The other is the plunge in repeated sixteenth-notes from A to B at m. 26, which will begin the descent from several of the work's climaxes.

This theme, in the high woodwinds, is mostly accompanied by a set of trichords that appear again and again, drawn from no particular row and not defining any clear twelve-tone aggregates.

In mm. 32-45 the first theme is then repeated with a similar accompaniment of tetrachords.

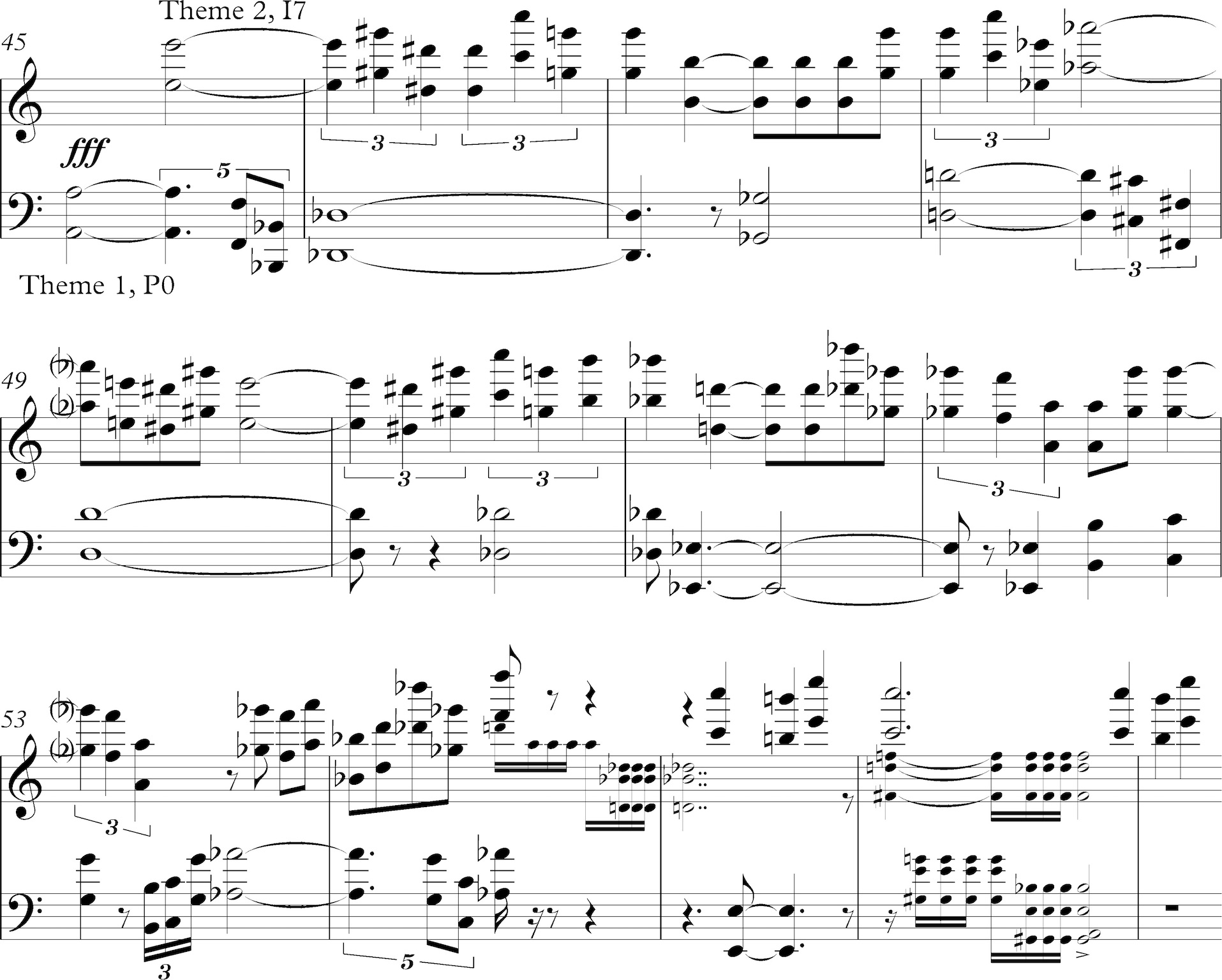

When the first theme again reaches its final E at measure 45, then these two main themes are heard in counterpoint together, at their original pitch levels, played by almost the entire orchestra, high instruments against low. Neither goes through its entire theme, and the texture breaks up into its repeated-chord climax, but one can tell how intricately Rochberg wrote these themes to fit together. The upper line is more rhythmically active, and repeats earlier row pitches more, so the switch between first and third hexachords comes at m. 51 in both lines.

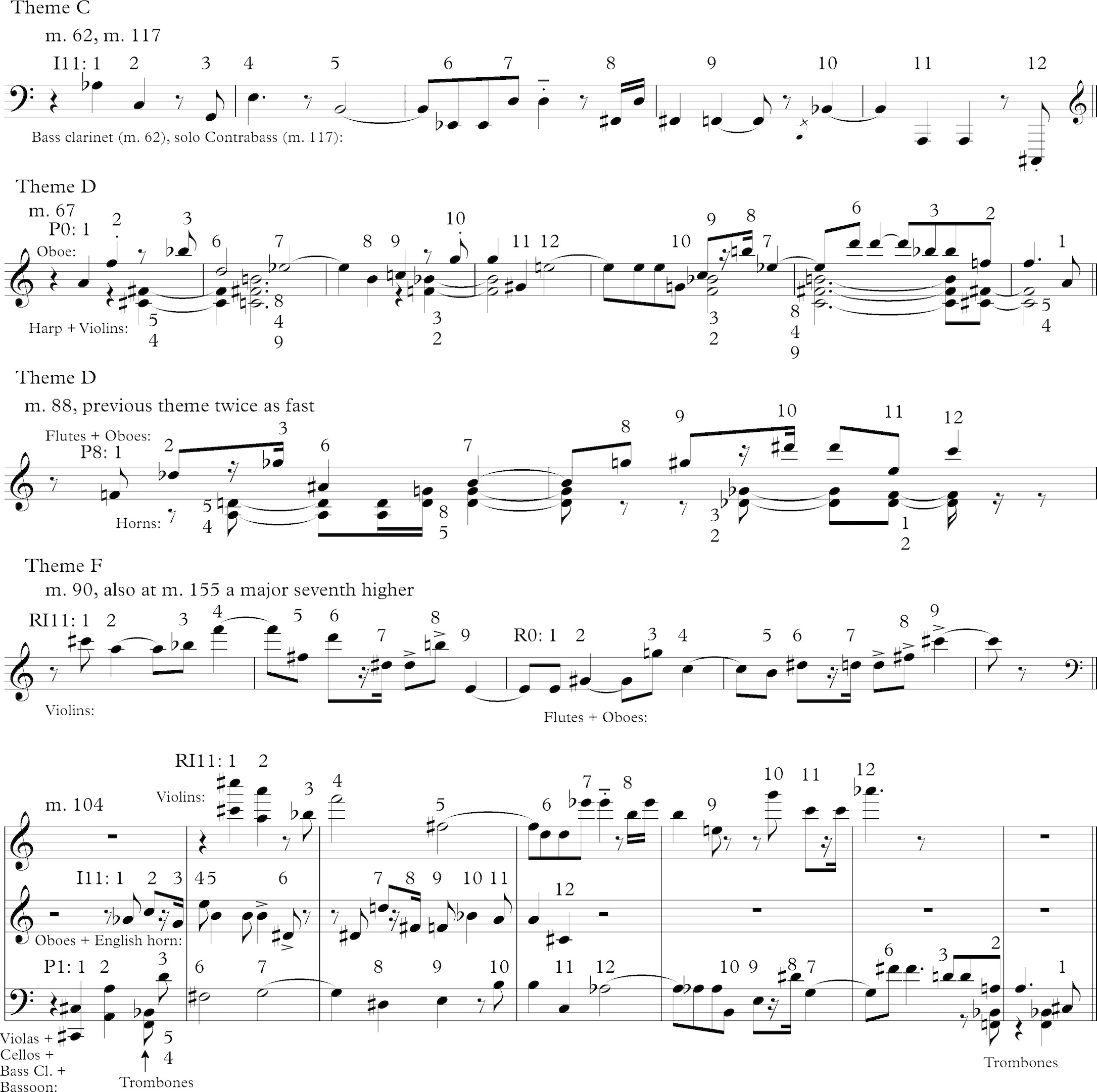

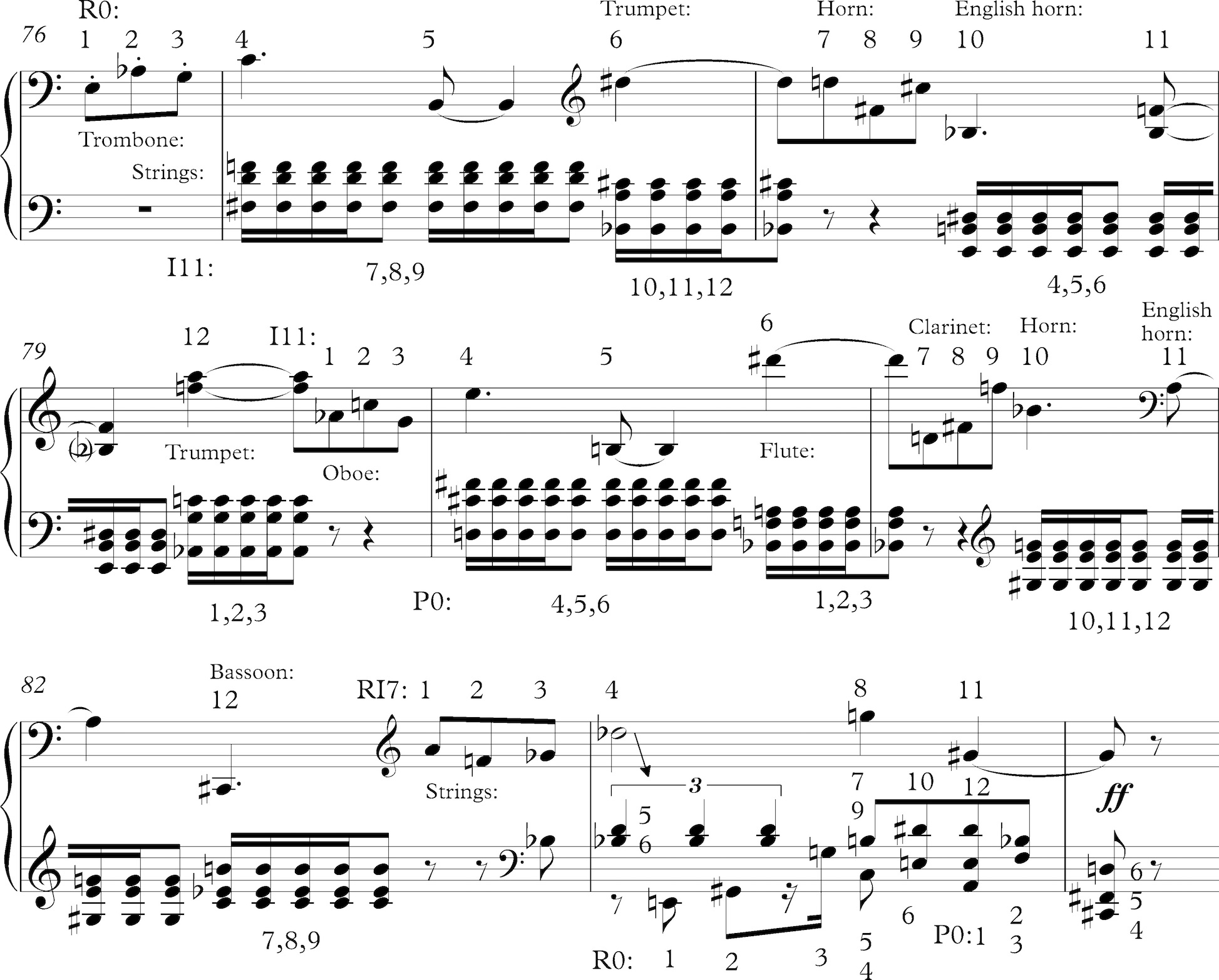

Following this contrapuntal showdown, mm. 62 to 122 are something of a calmer second-theme area. There are a number of recurring themes, all characterized by angular leaps, staccato notes, and a kind of Schoenbergian rhythmic squareness (or one might think of Mahler in his march mode). They all begin on off-beats, and balance slow notes in one measure with faster repeated notes in another, distinguished from the main two themes by a lack of triplets or quintuplets. It might work to consider them all variants on a theme, but Yoojin Kim labeled three discreet ones C, D, and F (the two main themes being A and B, of course), and for convenience in discussing them I'm going to retain those labels. Theme C comes back twice with almost no variation; Theme D, which hides some of the notes of its rows in the accompaniment, returns briefly twice as fast; Theme F is kind of catchy and high profile, particularly reminding me of Schoenberg. And at m. 104 theme D is heard in the bass with a variant of theme C above it - same contour, but using the retrograde of the original row.

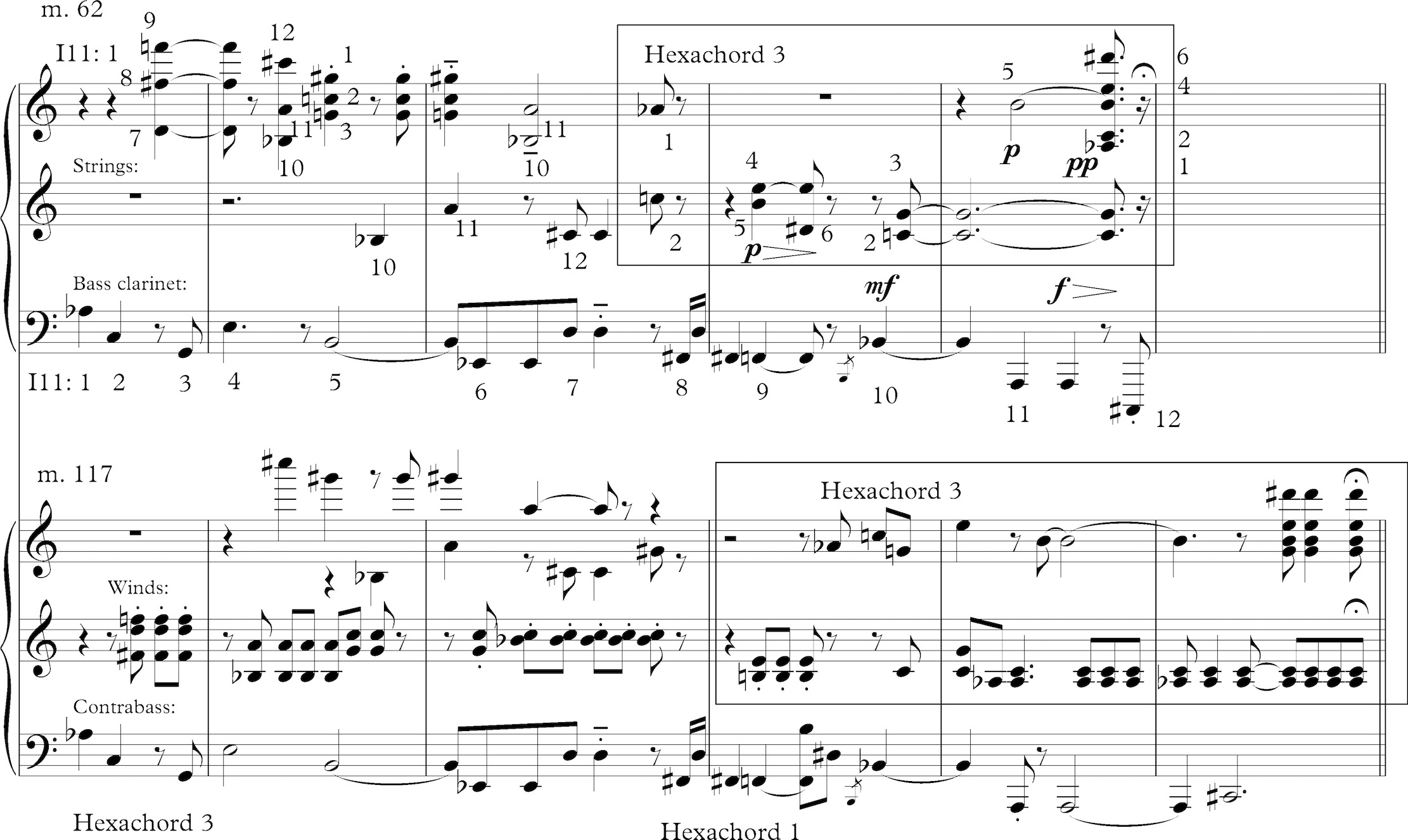

Theme C seems to have a transitional function. In its first appearance at m. 62, it winds down the energy from the counterpoint of the combined main themes, and brings the momentum to a momentary pause. Then, on its return at m. 117, it brings the exposition to an end with a similar pause. Comparison of these two passages provides an eloquent example of how Rochberg can shape two passages with the same rows, pitch-order be damned.

It will be noticed that I have bypassed E in my alphabet of themes, for the E theme is different and higher in profile. For the first time a rhythmic ostinato strikes up, but it is based on a dotted quarter unit, and the music seems to go into 12/8 meter for a few measures. The melody, too, bounces around in such large intervals that it has to fly from one instrument to another like one of Webern's klangfarben melodies. This theme, with its quasi-triplets, will not exactly return but will be unmistakably referred to in both the second and third movements.

This second half of the exposition, then, goes through these themes in the order CDEDF, transition, C+D,C. The transition, mm. 94-103 (Dr. Kim calls it theme G, but I see no particular theme to isolate) is a free section based on the first three pitches of the retrograde row, alternating on a major third and then leaping upward a major seventh. It floats back down in trichords and 16th-note alternations that follow no row, but switch from one hexachord to another.

The E theme will also return in the middle of the development, where it will be greatly extended and crescendo to a crashing climax. Theme F will also reappear in the development, and theme D will appear as a reminiscence in the third movement; theme C will not reappear after the development.

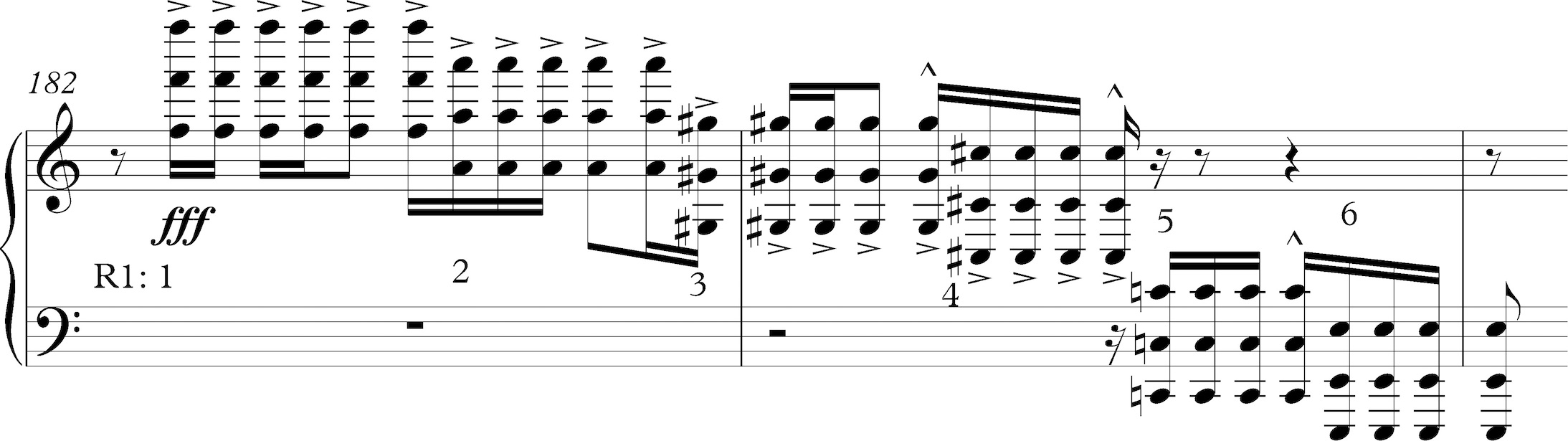

The development (mm. 123-205) is framed by recurrences of a new idea that seems unrelated to the other thematic material except for its quintuplet rhythms. It does, however, begin and end on subsets of the augmented scale. Over and over, in mm. 123-140 and again at mm. 185-202, various orchestral choirs move in acceleration through the following progression. It begins with a major/minor triad ([0347]), and, going through two [0257] tetrachords in the tiniest voice-leading, ends on another a tritone away. Inspection will reveal that the figure contains all twelve pitches. I will call this the wedge motive, since it always starts from a denser chord and spreads to a more open one.

Once these figures give way to a repeated-note climax in 16th-notes, the orchestra takes up the opening rhythm of the main theme and spreads it through an entire row.

The first half of the development, mm. 141-154, is a rather free texture of repeating trichords and tetrachords, linked by angular lines similar to the themes in the second theme area, but not bringing any of them back. In mm. 155-158 theme F returns, in inversion canon with itself, high instruments versus the low instruments. At m. 167 theme E returns, texturally thickened by echoes of the original line in other instruments, and extending its dotted-quarter pulse (with one actual 9/8 measure) until m. 182, when it crashes to a halt with one of the falling-repeated-note gestures that end so many sections here.

Immediately following, the strings start up the wedge motive again, which spreads through the orchestra in quintuplets, coming to a trilling climax at mm. 201-205.

The recapitulation (mm. 206-255) starts up right away by once again playing the second theme (at its original pitch) in counterpoint with the short, introductory motto form of the main theme. Though the main theme ends at m. 209, the second theme continues to m. 221, accompanied by repeating trichords and three-note motives. At m. 222 its final A turns once again into the first note of the main theme. This continues in its full form in the treble, with the second theme now played in the bass, the reverse of the arrangement in the exposition - a twelve-tone instance of invertible counterpoint. Now the orchestral texture is thickened, with repeating trichords entering from time to time. The higher theme, repeating its closing pitches over and over as if trying to gain momentum, finally incites one of the crashing climaxes at mm. 237-238.

As if rebounding from the crash, the orchestra builds up a twelve-pitch sonority a note or two at a time (mm. 239-241), and then builds up a different one (mm. 242-244), as the upper strings play a fortissimo melody. The melody contains only ten pitches, which seem to be best understood as the first six pitches of I5 except for Bb (hexachord 1) and the first six pitches of I3 except for Eb (hexachord 3 - the missing pitches are already being sounded if that's any consolation to anyone). The widely spread second chord is sustained for five measures (mm. 244-248), with an upward motive F#-Bb-A, common in the movement, repeating in the horns and cellos. There is no way to tie a full twelve-pitch chord to a specific row, but if you count it as I3 the last three notes are sustained in the bass, while notes 7-9 are the repeating motive. The four-note chord at the top, G#-B-D#-G is a [0148] set, a transposition of the symphony's opening four notes, so the way the full twelve-pitch sonority is laid out does have thematic significance.

As a bridge to the next movement, played attaca, various solo winds and strings play seven measures of quiet row segments, in which the bass clarinet circles the edge motive from the second theme.

Second movement -- mm. 256-572

A section -- mm. 256-362

Idea 1 -- mm. 256-276

Idea 2 -- mm. 277-295

Idea 3 -- mm. 296-335

Idea 4 -- mm. 336-362

B section -- mm. 363-416

First half with theme E -- mm. 363-379

Second half, two themes -- mm. 380-416

A section -- mm. 417-572

Idea 1 -- mm. 417-437

Idea 2 -- mm. 438-454

Idea 3 -- mm. 455-494

Idea 4 -- mm. 495-528

Coda -- mm. 529-572

Idea 2 theme -- mm. 529-559

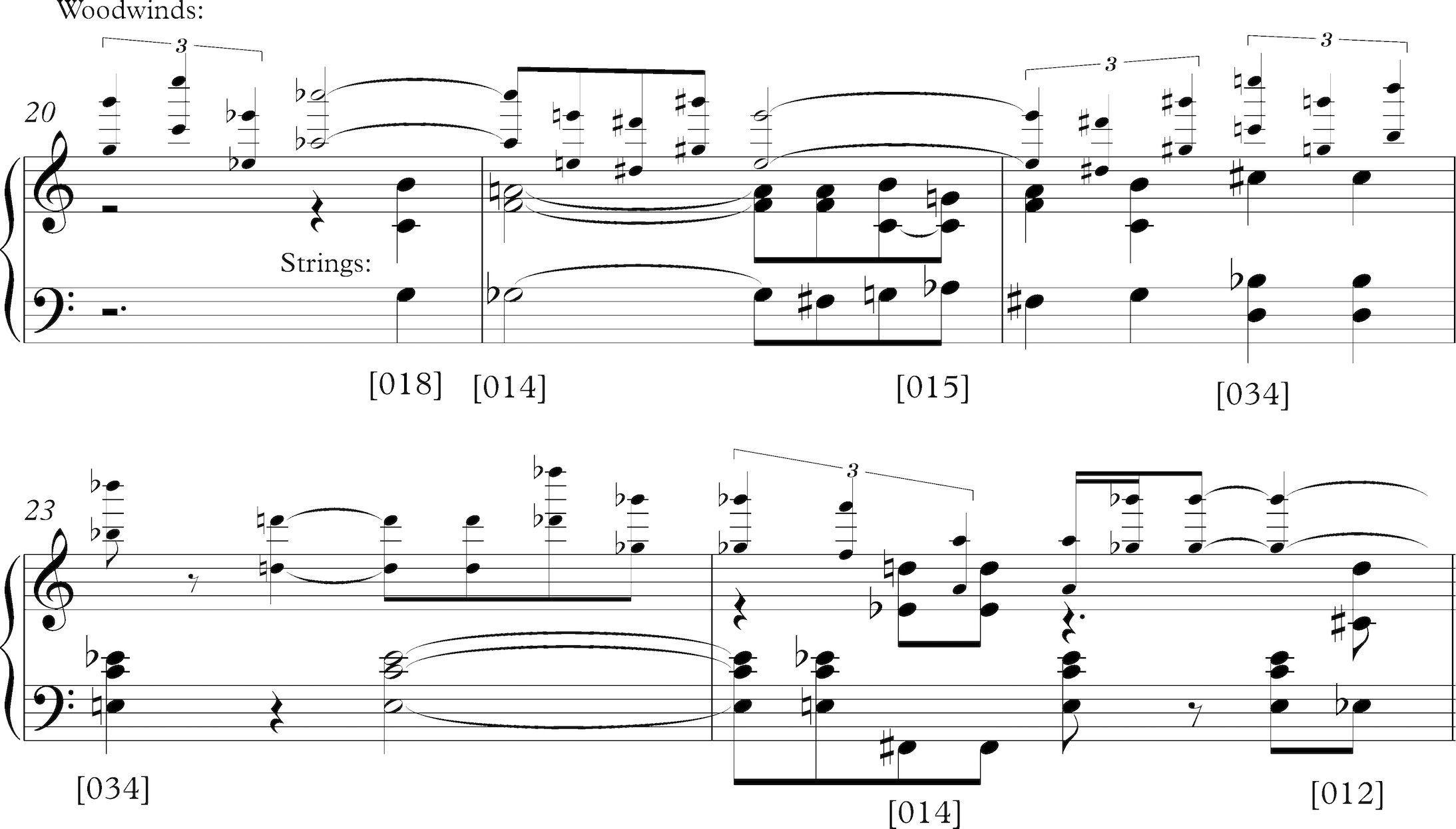

Perfect 5ths and 4ths -- mm. 560-572At 317 measures, the second movement would seem to be a monster of a scherzo, and it is large and highly sectional, but its ABA form is clear (and the third movement will be ABA as well). It is well contrasted with the first movement, in that instead of the latter's dynamic arcs of movement through pitch sets, the A sections here are static mosaics of fragments built up by additive process. Rochberg is even less interested here about strict row order than he was in the first movement, but there is plenty of playing around with trichords that make up twelve-tone aggregates (as grad theory students learn to call them - complete sets of the twelve pitches).

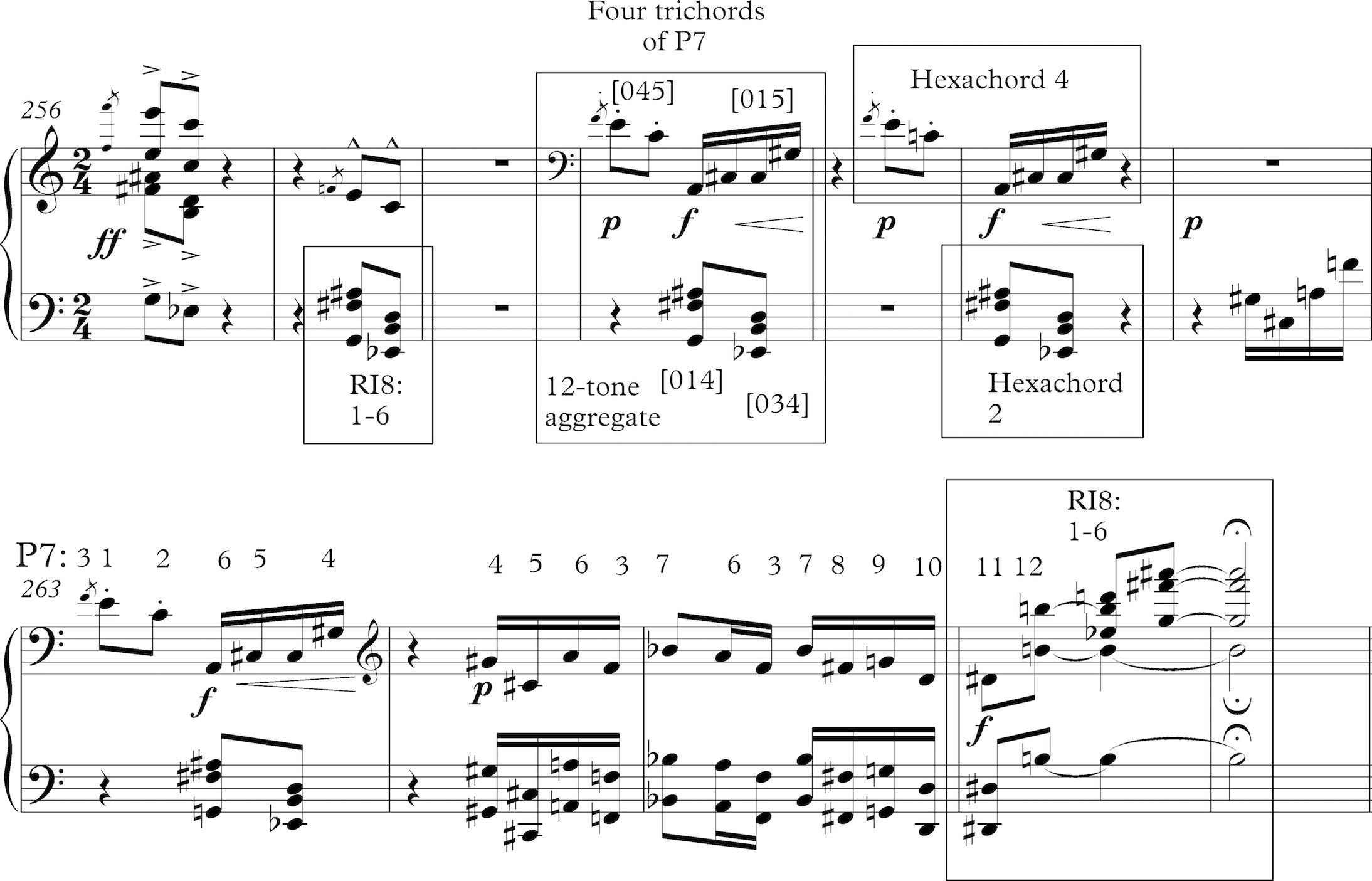

It would be less accurate to talk about themes here than to isolate textures grouping together interlocking figures. What I'm going to call idea 1 occupies mm. 256-276 in the first A section and 417-437 in the second A section: 21 measures each time, and very much the same except re-orchestrated, and with a few figures added or omitted. The example gives the first twelve measures, with several possible ways of showing the pitch relationships. The opening melodic motive F-E-C does not appear in any row, but it is the first three pitches of P7 out of order. The trichords beneath it, A#-F#-G and D-Eb-B, are the first trichords of RI8. In m. 259 Rochberg adds in A-C#-G#, and we have the four trichords that make up row P7. In mm. 263-266, the melody goes through all twelve pitches so out of order that it could look like I chose a row at random, but the first three pitches of P7 are at the beginning and the last five at the end. Also, after the first movement's fixation on hexachords 1 and 3, the switch here to 2 and 4 may have been intended as some welcome variety - at least for the composer, if not perceptibly for the listener.

Dominating mm. 277-295 in the first A section and 438-454 in the second, idea 2, though it expresses an aggregate, does not seem to relate to the row; neither the alternating trichords in the treble nor the 16th-notes underneath belong to one of our augmented scale hexachords, though the tag that develops after it is hexachord 2.

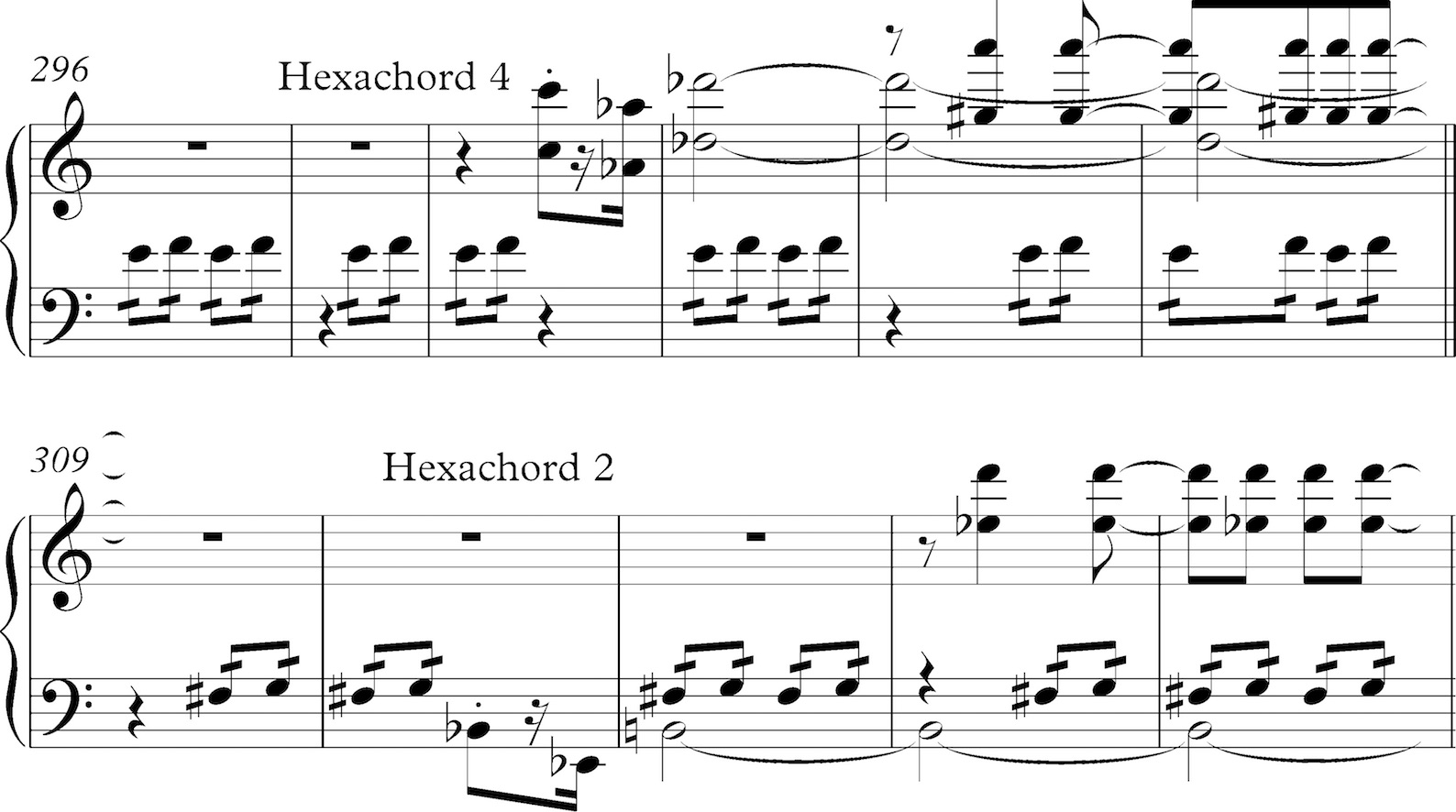

Idea 3 (mm. 296-335 and 455-494) turns the opening E-F of idea 1 into a buzzing ostinato underneath a three-note motive answered by syncopated dyads, all grouped in hexachords.

The passage builds up into four-note (three-pitch) motives that echo the four disjunct trichords around the orchestra.

Idea 4, occupying mm. 336-362 and 495-528, is less distinctive. Idea 3 ends with repeated chords, and idea 4, starting with a reduction in dynamics and forces, builds up a series of rows through repeated and sustained notes until by the end of each phrase as many as eight pitches are still present. At m. 348, however, a grand theme based on the row breaks out, something like a march version of the main theme, leading the first A section to an abrupt halt.

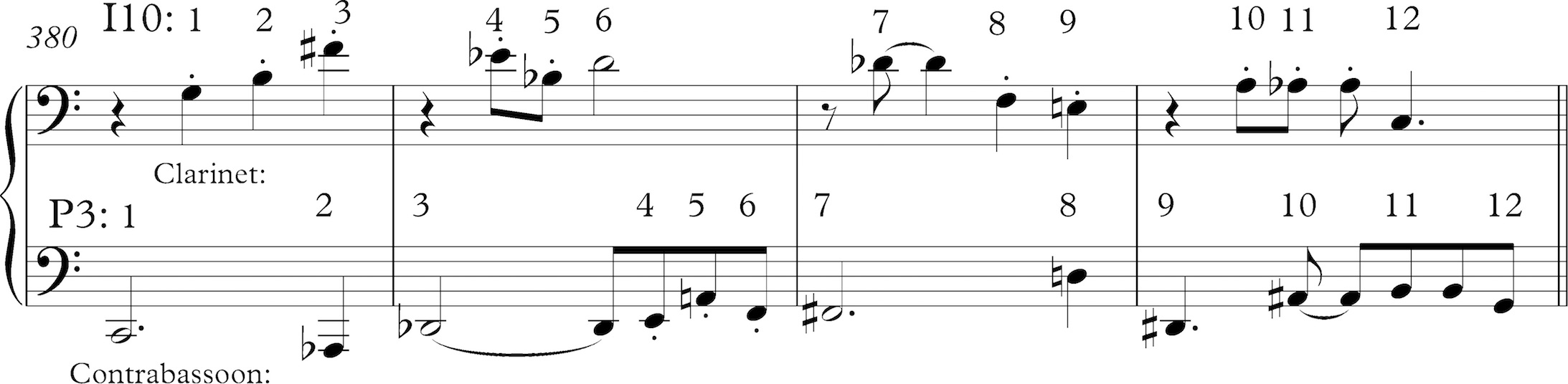

The scherzo's B section starts up more quietly, and the style now becomes more contrapuntal and continuous. The entire B section is based on two four-measure themes that go together, plus motives spun off from them. For our brief purpose of discussion I will call the upper one based on I10 the inversion theme and the lower one based on P3 the prime theme. The inversion theme here is first heard by itself, and afterward they are always found together, at mm. 380, 384, 388, and 398 (and at m. 384, the inversion theme is played at two transposition levels at once, the rhythm slightly differing).

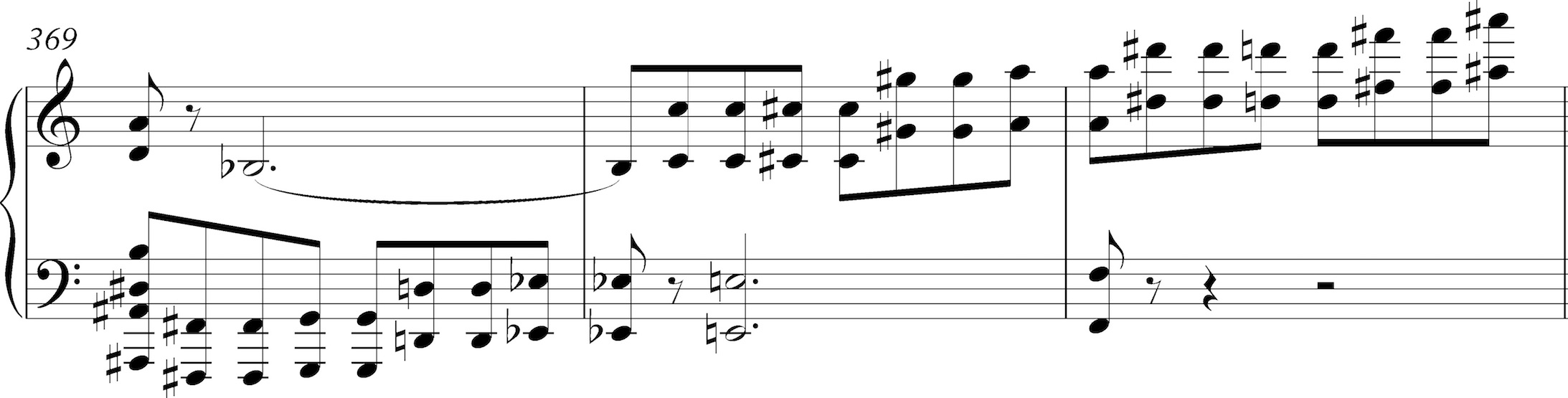

Several motives from these themes become independent. Notes 8, 9, 10, and 11 from the prime version, with their rising alternations of half-steps and perfect fifths, become a crescendo-building device at mm. 369 and again at 394.

Following the first of these crescendos, notes 10, 11, and 12 from the inversion swing into a quasi-12/8 meter pattern clearly evoking Theme E from the first movement.

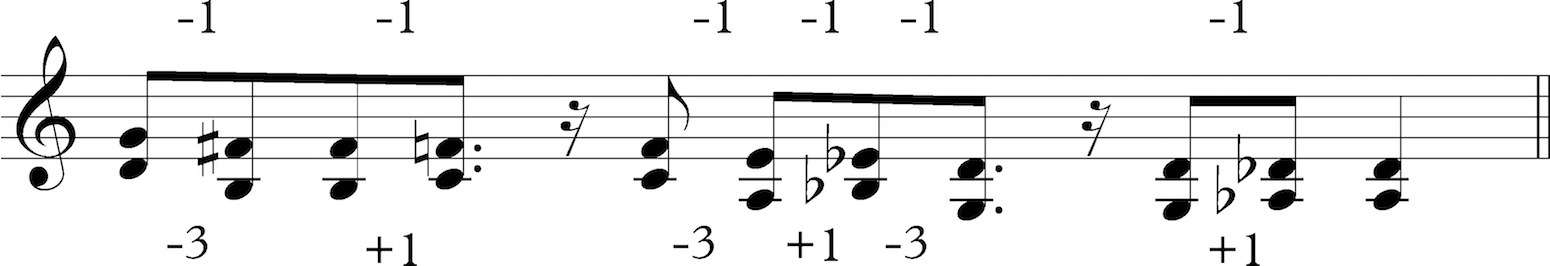

After this climax, at m. 380 the texture thins down to the two themes without further accompaniment. Their climactic statement (following the second rising pattern) at m. 398 switches them in invertible counterpoint, so that the prime is now on top and the inversion on the bottom. Then the last four notes from the prime and the last three from the inversion begin to sequence downward through various rows.

The repetition of these figures at various transpositions continues in decrescendo, dropping down into the bass register, finally coming to an inconclusive halt.

As mentioned before, the second A section, which now returns differs from the first in details of orchestration and placing of figures, but measure by measure it tracks pretty closely; the differences are more easily seen in the score than described. At mm. 522-526 there is a five-measure, regressive extension of idea 4, and then two quick measures of rest before the coda. The coda (mm. 529-572) is in two parts. The first is generally derived from the movement's idea 2; the second is an anomalous continuum of perfect fifths and fourths appearing around the orchestra, giving a welcome relief from the major sevenths that pervade the work.

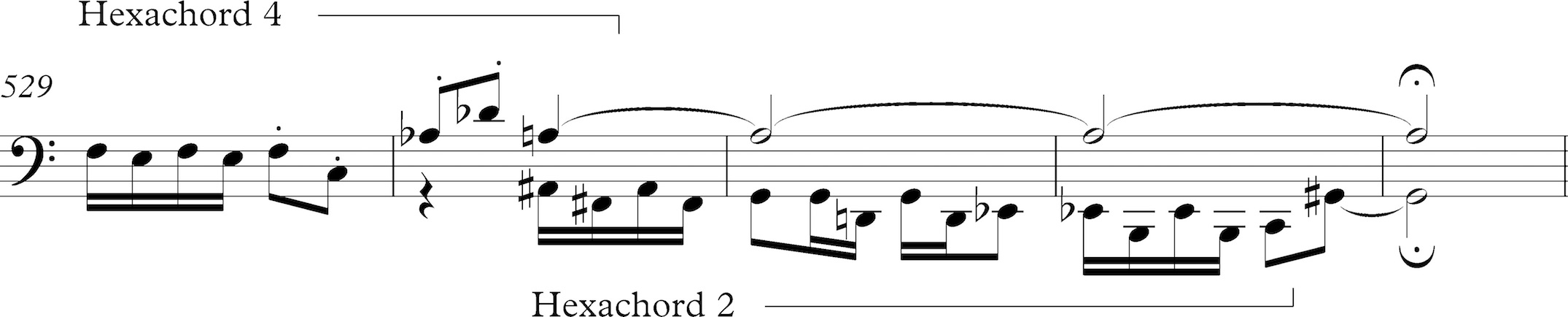

First Rochberg extracts a little tune from hexachords 2 and 4, using patterns from idea 1.

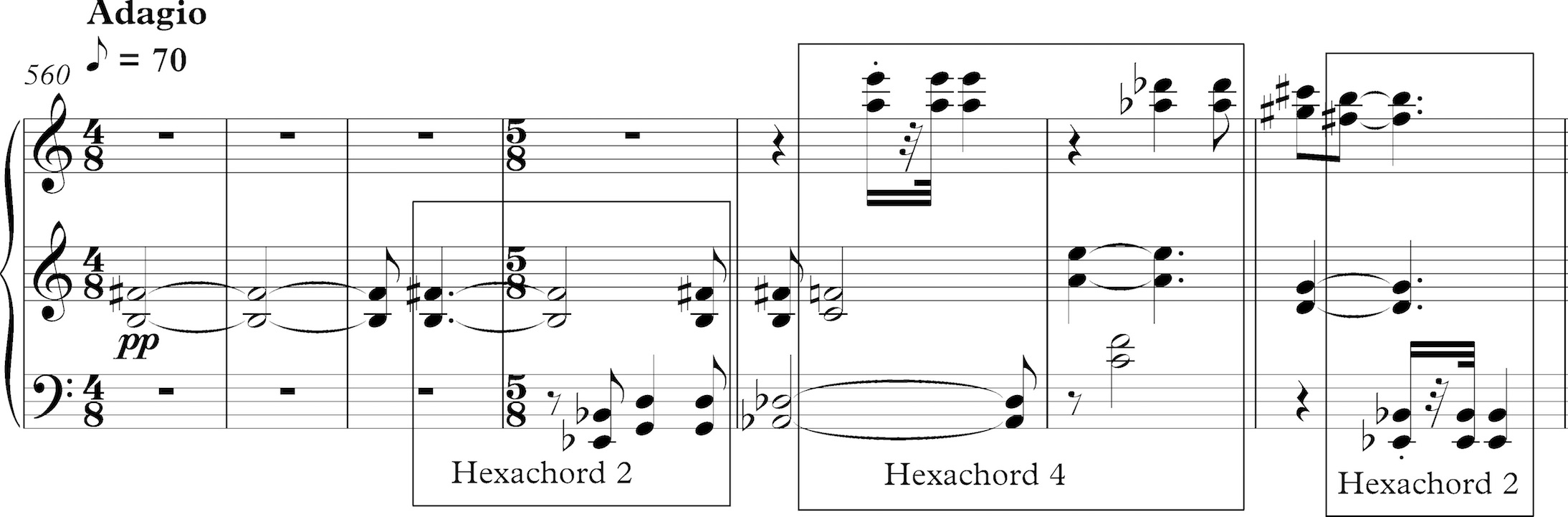

Twice (at mm. 534 and 542) this texture goes into the alternating chords of idea 2, and then it descends in motoric 16th-notes into a crashing climax (mm. 555-559) with a new trichord on every quarter-note beat. A quiet perfect fifth B-F# is sustained from this melee by the brass and clarinets, and it turns into the mysterious transition to the third movement. At first Rochberg groups the fifths with their roots related by augmented triads, so that the augmented-scale hexachords are heard together in configurations we haven't heard yet.

He then begins descending through a pattern (used between fifths and fourths in different instruments, as well as between those in the same instrument) of descending half-steps on the top line, and alternating descending minor thirds with ascending half-steps in the lower line so that fourths and fifth alternate.

(Since every dyad in this passage is a fourth or fifth, one might suspect the presence of two parallel rows, but this does not appear to be the case.)

Third Movement -- mm. 573-656

A section -- mm. 573-597

-----Theme 1, P0 -- mm. 573-584

-----Theme 2, RI8 -- mm. 585-597

B section -- mm. 598-627

-----Phrase 1 -- mm. 598-602

-----Phrase 2 -- mm. 603-607

-----Phrase 3 -- mm. 608-617

-----Phrase 4 -- mm. 618-625

-----Phrase 5 -- mm. 626-627

A section -- mm. 628-646

-----Theme 2, RI8 -- mm. 628-646

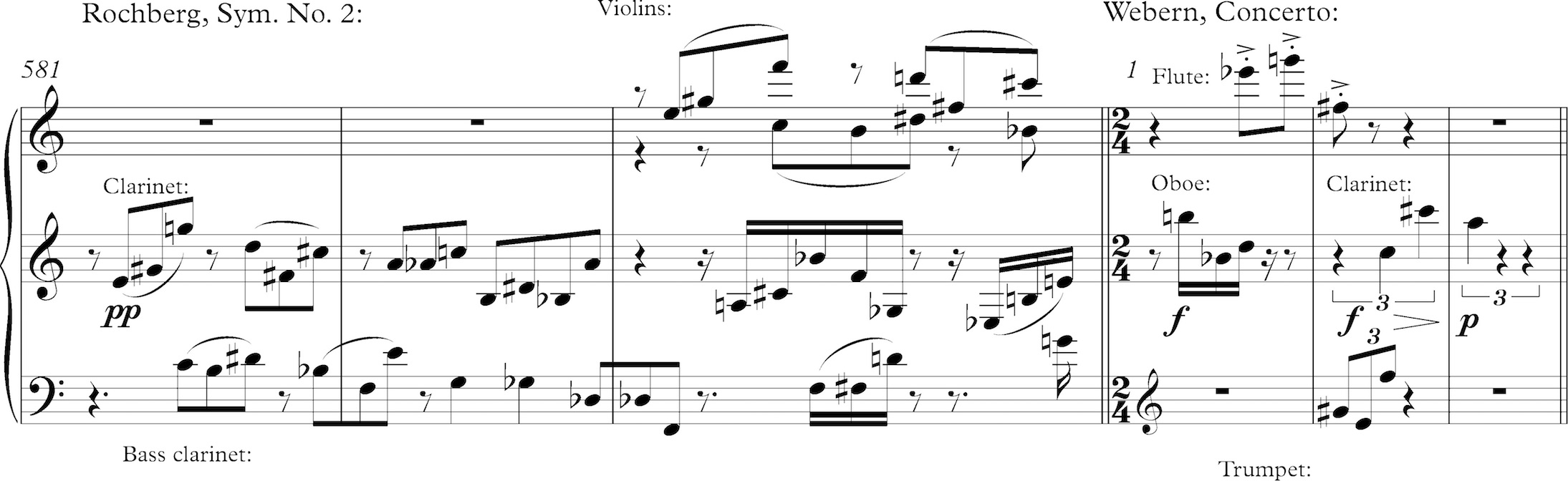

Coda: Collage of returning ideas -- mm. 647-656A decade before Rochberg wrote this symphony, Shostakovich's "Leningrad" Symphony received a celebrated American premiere; Bela Bartok was so unimpressed with it that he satirized one of the work's themes in his Concerto for Orchestra. Rochberg makes a similar gesture in his third movement with respect to Anton Webern. The third, slow movement is an ABA form. The A sections are quiet, square, four-bar complementary melodies, like stupidly simple twelve-tone counterpoint exercises. At the end, each goes into a texture of angular three-note motives unmistakably reminiscent of Webern, in fact so similar to the first movement of his Op. 24 Concerto that I checked to see if it's a quotation.

The B section, by extreme contrast, is a nightmare, a phantasmagoria, the symphony's most complex music yet. It's like the orchestra wakes up angry and irrational, asking the same question over and over and getting different answers. It's as though the A sections represent a repressed, sterile state of mind from which the B section violently and instinctively rebels. Did Rochberg mean for the contrast to imply that Webern's music was simplistic and square?

Amy Lynn Wlodarski's new biography George Rochberg, American Composer: Personal Trauma and Artistic Creativity has this to say on pp. 62-63:

"In 1958 [Rochberg] wrote with some concern about Webern's music, arguing that its spatial dispersion of the row had ultimately constricted music's expressivity and set a dangerous example for current modernists. 'As narrow as Webern's emotional range seems,' he remarked, 'that's how much narrower Stockhausen's range seems...'

"To him, the stasis inherent in Webern's music, which Rochberg understood as resulting from the composer's reliance on a highly self-referential harmonic system, became prescient of the traumatized state of the postwar world - its emotional withdrawal, its sense of increasing claustrophobia, its tightly constructed spaces... The result... was 'a thin world of music, monotonous in its extremely limited images and gestures,' that left the listener not just dissatisfied but numb."

That thin, monotonous music sounds very much like it could be the A sections of this movement. Like Bartok before him, Rochberg used the contrasts to caricature a composer he considered overrated.

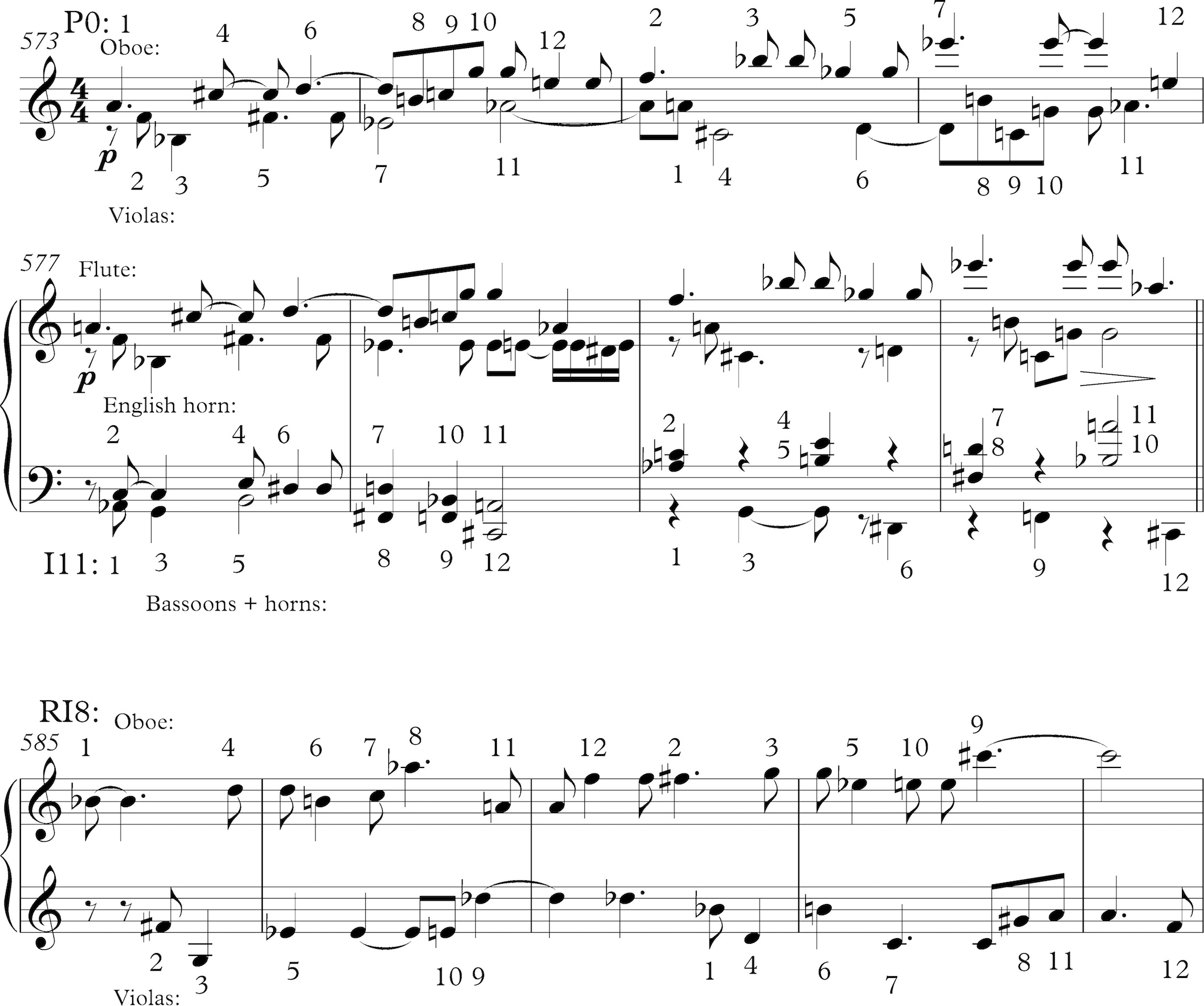

Accordingly, the A material is easily described. Twice (at mm. 573-576 and 585-588) a two-part texture is derived from a single row that bounces between the two lines. These four-bar themes are then immediately repeated (with minor variations, mm. 577-580 and 589-592) with another two or three lines added below, using a complementary row. Note that in the original four-bar phrases Rochberg generally places the top melody's notes in the lower melody for the second half, and vice versa. The first such themes are given here, with the expanded version of the first one.

Each eight-bar phrase is then followed by the pointillistic texture of angular three-note motives (mm. 581-585 and 593-597) that is so so strikingly reminiscent of Webern, especially the first movement of his Concerto Op. 24, even in some cases the same trichords.

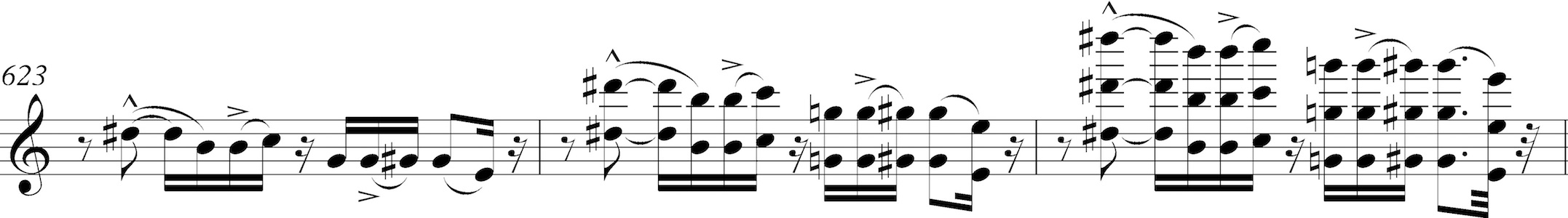

The rhapsodic and irregular B section, with its angular lines of 32nd-notes skittering through the entire orchestra, is far more difficult to sum up; I will attempt to point out the foregrounded elements. Its brooding recitative features a recurring melody in pairs of three or four-note phrases, always with a pair of grace notes on one note. Like the trumpet theme in Ives's The Unanswered Question, it returns five times and seems to seek a response. The five phrases seem designed around segments of the row that have not been used so far motivically, such as using notes 2, 3, 4, and 5 of a row, or notes 6, 7, 8, and 9. The missing notes of the row are often found in accompanying chords, but as Rochberg goes on the writing becomes freer and freer.

Each of these phrases is answered by a different gesture. I give here the sites of the five phrases, with a description of the material that follows each one in response:

Phrase 1, mm 598-602: leaping 32nd-note lines leading to, and accompanying, an angular line in the first violins.

Phrase 2, mm. 603-607: a quiet series of repeating 16th-note chords with changing dissonances.

Phrase 3, mm. 608-617: the return of Theme D from the first movement, as a reminiscence; denser, but with some of the same harmonic elements; at m. 615, where the original Theme D went into the quasi-12/8 Theme E, this goes back into the frantic texture of phrase 1.

Phrase 4, mm. 618-625: a return of the wedge motive, followed by an insistent phrase repeated three times notes 7 through 12 of P0):

Phrase 5, mm. 626-627: its second motive much softer in the bass clarinet, this slides quickly into the second A section.

The second A section, mm. 628-640, repeats the second half of the first A section, with some alterations. The remainder of the movement, mm. 641-656, is a whirlwind collage of earlier ideas:

mm. 641-643: the wedge motive

mm. 643-644: motives like those of phrase 1 above

mm. 645-646: three-note motives from the Webernesque part of the A section

mm. 647-651: a couple of phrases from Theme E, brought back sardonically amid silences

mm. 653-656: motives from the second movement's idea 1Something like the quotations from earlier movements at the beginning of the finale of Beethoven's Ninth Symphony (if on a much briefer level), this succession of fragments builds up an expectation of some big new thing, and what we get is the beginning of the fourth movement, opening with the first movement's initial motto, though at a different transposition level.

Fourth movement -- mm. 657-795

Introduction -- mm. 657-662

Chorale -- mm. 663-724

Twelve-pitch chords -- mm. 725-733

Theme A -- mm. 734-746

Transition -- mm. 747-753

Wedge motive -- mm. 754-759

Closing transition -- mm. 760-769

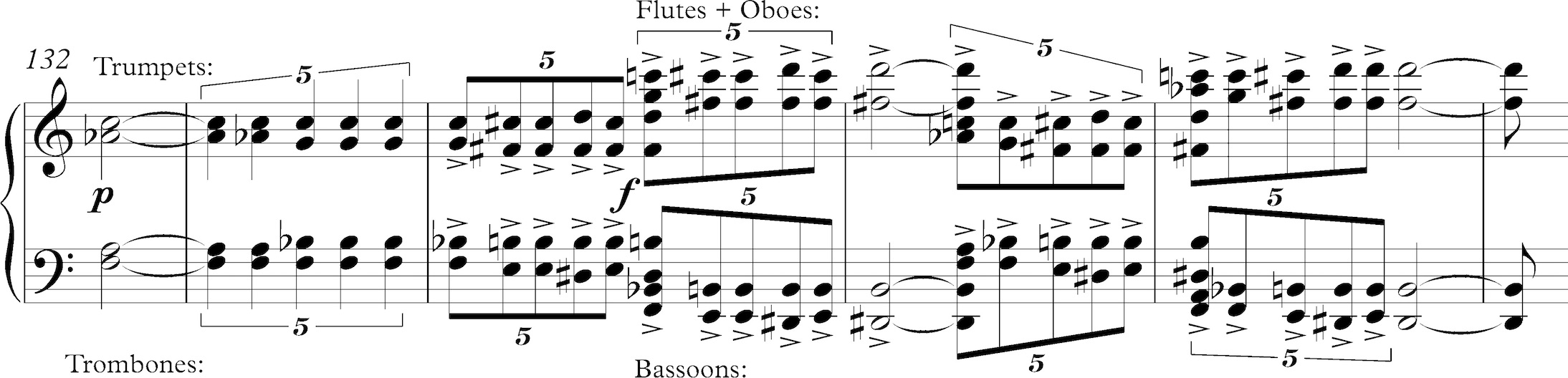

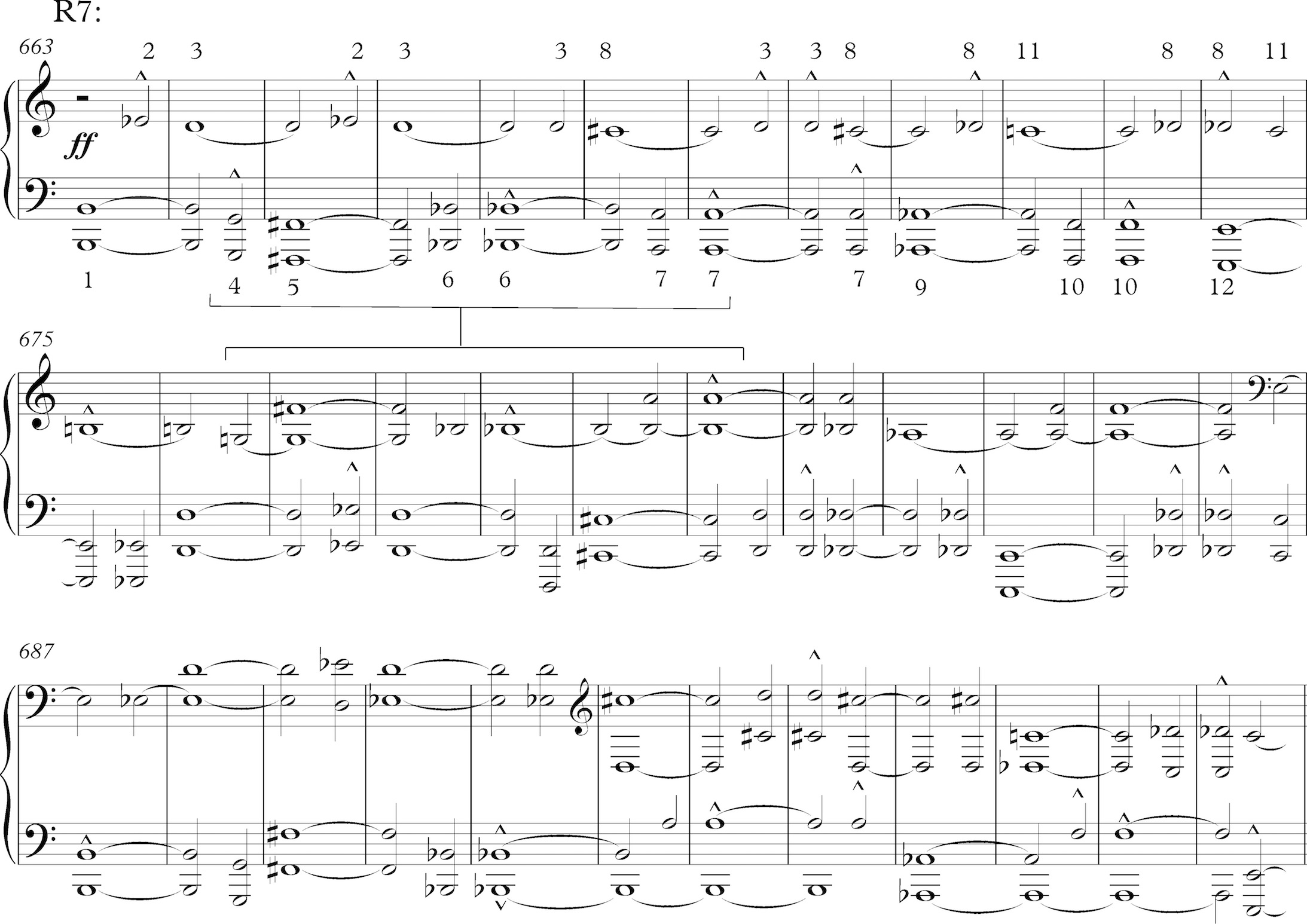

Coda -- mm. 770-795The final movement begins with an explosive return of the symphony's opening motive - transposed down a major third to P8 (mm. 657-662) - inciting a scrambling of twelve-tone rows in octaves through the strings and winds that first soar upward and then come down to crash on a low B. The next large section, comprising more than half of the movement (mm. 663-724), is a steely, crescendoing, but basically rather simple chorale. It states R7 over and over every twelve measures, in the following arrangement, dividing the twelve pitches between two lines. Actually, the eighth tone always appears before the seventh and the eleventh before the tenth, so one could justifiably say that the row used here is B-Eb-D-G-F#-Bb-C#-A-Ab-C-F-E.

In mm. 663-674, four pitches of the row are used in the upper line and the other eight in the lower line. One line starts on B and moves around, the other starts on Eb and gradually moves down chromatically to B to begin the next cycle. Note that they are arranged so that there is only half-step motion in the upper line and half-steps and major thirds in the lower line. At m. 675 the lines cycle again, switched so that the bottom one is now on top. At m. 687 they switch again, and so it continues, sustaining more and more pitches from the row as it goes on, as though the orchestra had a giant sustain pedal.

The chorale goes through five such cycles in sixty measures, and starting at m. 685 the symphony's opening motto starts appearing in bursts of quintuplets and sextuplets in the massed woodwinds.

To have created a sixty-measure crescendo of dynamics, register, and dissonance by cycling through only one row form is an impressive achievement, and its simplicity makes an effective climactic gesture for the whole symphony.

At m. 723 the orchestra leaps downward through one of its repeated-note descents in the first hexachord of R7. Measures 725-733 then recreate the two twelve-pitch chords heard in the first movement at mm. 239-248, in a different configuration but again with the three-note repeating motive in the horn, and with G#-B-D#-G in the high woodwinds over a low F in the basses. The horn's final A becomes the first note of the return of the main theme (mm. 734-746). This is a recapitulation in every sense, and although the texture is thickened and a few lines are added, the harmonic elements and even much of the rhythm are repeated much as they originally were in mm. 5-15.

The rest is anticlimax. A transition in mm. 747-753 weaves twelve-tone rows through two lines in the strings, leading to a final statement of the wedge motive in the brass in mm. 754-759. Measures 760-769 make a melody from R2, the first half in the violas and cellos and second half in the clarinet, accompanied by faster row fragments below. (An anomaly in m. 761 has the bass clarinet playing two quarter-note G's in near-unison with two quarter-note G#'s in the double bass. Both pitches are needed for the segment of RI1 used here, but this is so contrary to Rochberg's usage that I wonder if it's a mistake.)

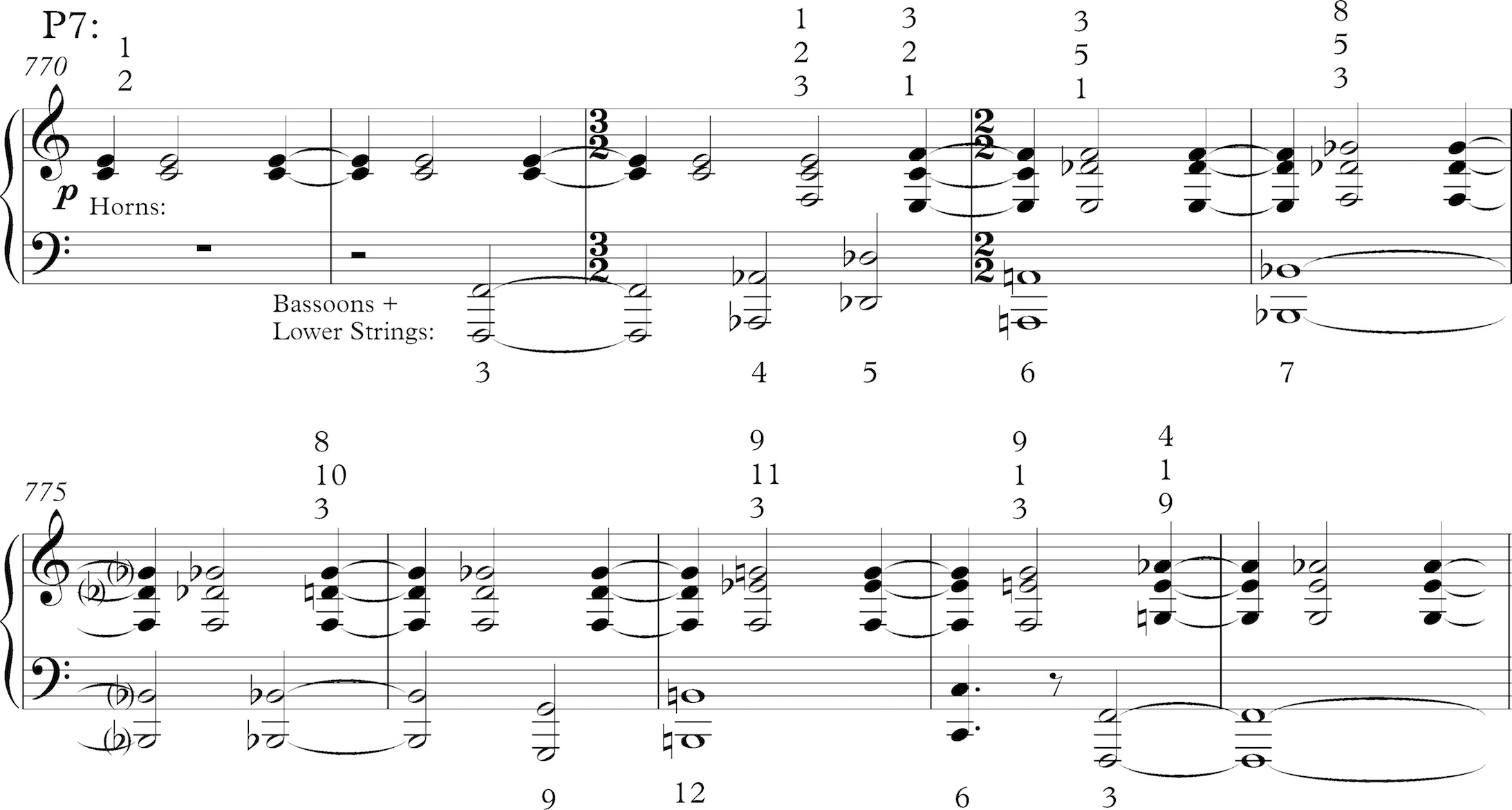

Finally, at m. 770 two horns enter softly repeating a third C and E, the first two notes of P7. The bassoons and lower strings enter with the fifth through seventh notes, and finally the ninth and twelfth, but the others are in the chromatically spreading horn trichords above.

This soft coda starts over with the C and E in the violins (m. 780), and this time the upper chords spread into the flutes and clarinets. Reiterating the example above, this massive symphony ends in virtual stillness, with an F in the bass and G, E, and Ab above, notes 1, 3, 4, and 9 of P7. The implied F-Ab-E minor-major seventh chord is perhaps a reference to the opening row, but this is a mystic and inconclusive ending.

Although the four movements are distinct, they are meant to be played attaca, without pause. As in Liszt's four-movements-in-one piano sonata, the last movement doubles as a second and more final recapitulation to the first. The narrative arc draws the four movements together quite well. The first movement exhausts itself with its two main themes, from which the milder second thematic area seems little more than a digression. The scherzo picks up in a different vein altogether, beginning in erratic playfulness and ending in quiet mystery. The third movement deliberately reaches a sterile point that Rochberg thought Webern's music represented, and revolts from it; the variety in the responses to its central five phrases forecasts the even greater dissociation and fragmentation in its final transition. In context the finale's opening motto seems at first just another reminiscence, and then the sixty-measure chorale theme seems to gather up all of the emotional energy built up so far and focus it, leading it to a climactic recapitulation of the main theme. The final coda seems to take place on a field devastated by battle, with none of the protagonists still standing. The quotation of an earlier movement in a later movement, which may have begun with Haydn's Symphony No. 47, was made famous by Beethoven's Fifth and Ninth Symphonies, of course, and led to the genre of the cyclic symphony starting with Berlioz's Symphonie Fantastique. The intensely psychological cast Rochberg gives to the process here is, I think, a new contribution to the technique.

That said, I think one could charge that the first and last movements are much higher-profile than the inner two, which are less clear and memorable. The collage technique that opens the second movement gives way in the middle to a contrapuntal texture not well differentiated from the first movement's second thematic area, and the number of transitions works against the sweep of the overall form. The third movement's reference to Webern's style, a recognition of which I think is necessary to the movement's meaning, is not nearly as clearly drawn as, say, Bartok's satire on Shostakovich in his Concerto for Orchestra, and is probably too subtle for most even highly literate listeners to read meaningfully. As a result, the arc of the first and final movements makes a brilliant impression, but what happens in between is not as well defined. The symphony's energy is powerful, but, without analysis of the kind we've done here, the meaning of some of its gestures remains obscure.

Copyright 2019 Kyle Gann

Return to American Symphonies

Return to the home page