Florence Price: Symphony No. 3 (1940)

Analysis by Kyle Gann

All score reductions by the author

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 3.0 License.Of Florence Price's (1887-1953) four symphonies, the Second has gone missing. The First (1931-2) is fairly conventional, reminiscent of Dvorak, though with a highly original slow movement emphasizing seven-measure phrases. The Third (1938-40), from its opening measures, takes more risks, indulges some strange formal asymmetries, breaks into dissonances occasionally for their own sake, and also, in its third movement, engages African-American idioms more expertly (though the First Symphony's more modest scherzo does this as well). It nurtures some anger - we need not look too far into Price's biography to imagine why the first important African-American female symphonist may have wanted to rail against the world late in her career - yet also some playfulness and affection for jazz and ragtime idioms. The Fourth Symphony is her most polished and again more sedate, somewhat elegiac in character. All three symphonies have Juba or Juba Dance as a third movement title, and those movements engage African-American musical idioms; this third movement does so with a greater stylistic range than the other two. All final movements are also in 6/8 meter, and in the Third and Fourth Symphonies are titled as Scherzos. Choosing only one of the symphonies, this early in a major revival of interest in her music, was difficult, but the Third piqued my interest as the most original, personal, and uninhibited of the three, if also perhaps the most problematic.

First movement

Slow introduction -- mm. 1-18

Exposition -- mm. 19-132

First theme -- mm. 19-30

Transitional area -- mm. 31-44

Anticipation of second theme -- mm. 45-61

Transitional area reprise -- mm. 62-77

Second theme -- mm. 78-93

Second theme repeat -- mm. 94-109

Closing theme area -- mm. 110-132Development -- mm. 133-168

Modulating devel. of first theme -- mm. 133-151

Ideas from transitional area -- mm. 152-163

Transition in octaves -- mm. 164-168Recapitulation -- mm. 169-212

First theme and transition -- mm. 169-193

Restatement of second theme in C minor -- mm. 194-212Coda -- mm. 213-253

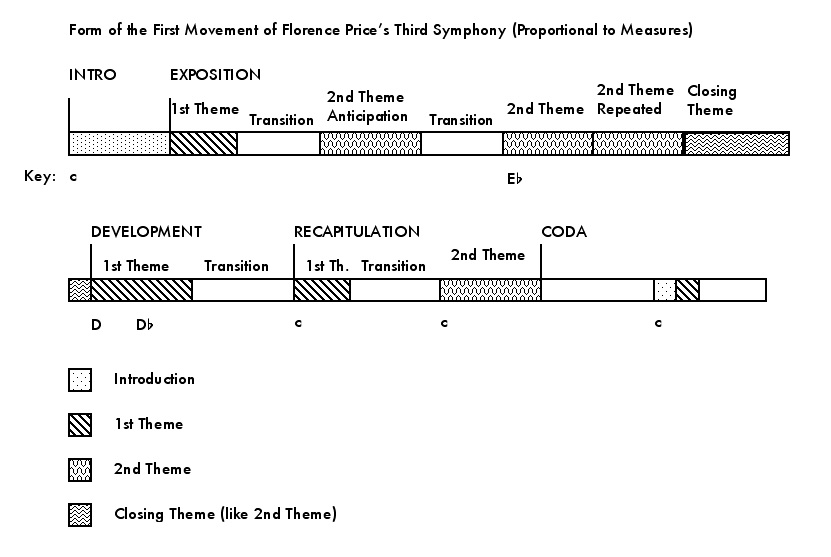

The first movement is peculiar in form, though its overall gesture is clear. Following a dirge-like introduction, the first theme is impetuous, masculine, and briefly treated. The middle of the transition material contains a long anticipation of the quiet, pentatonic second theme, and when that theme finally arrives in Eb major Price plays it twice in its entirety, and then continues to dwell at unusual length in its idyllic simplicity. In the recapitulation the second theme returns only in a particularly bitter statement in C minor; one senses in retrospect that the long sojourn in Eb pentatonic represented a reluctance to leave its placid restfulness, as if the music knows that its eventual return in C minor is a return to the unhappiness (and masculinity) of the real world. The very form of the movement depicts resentment and anger about the impossibility of remaining unmolested in a peaceful place.

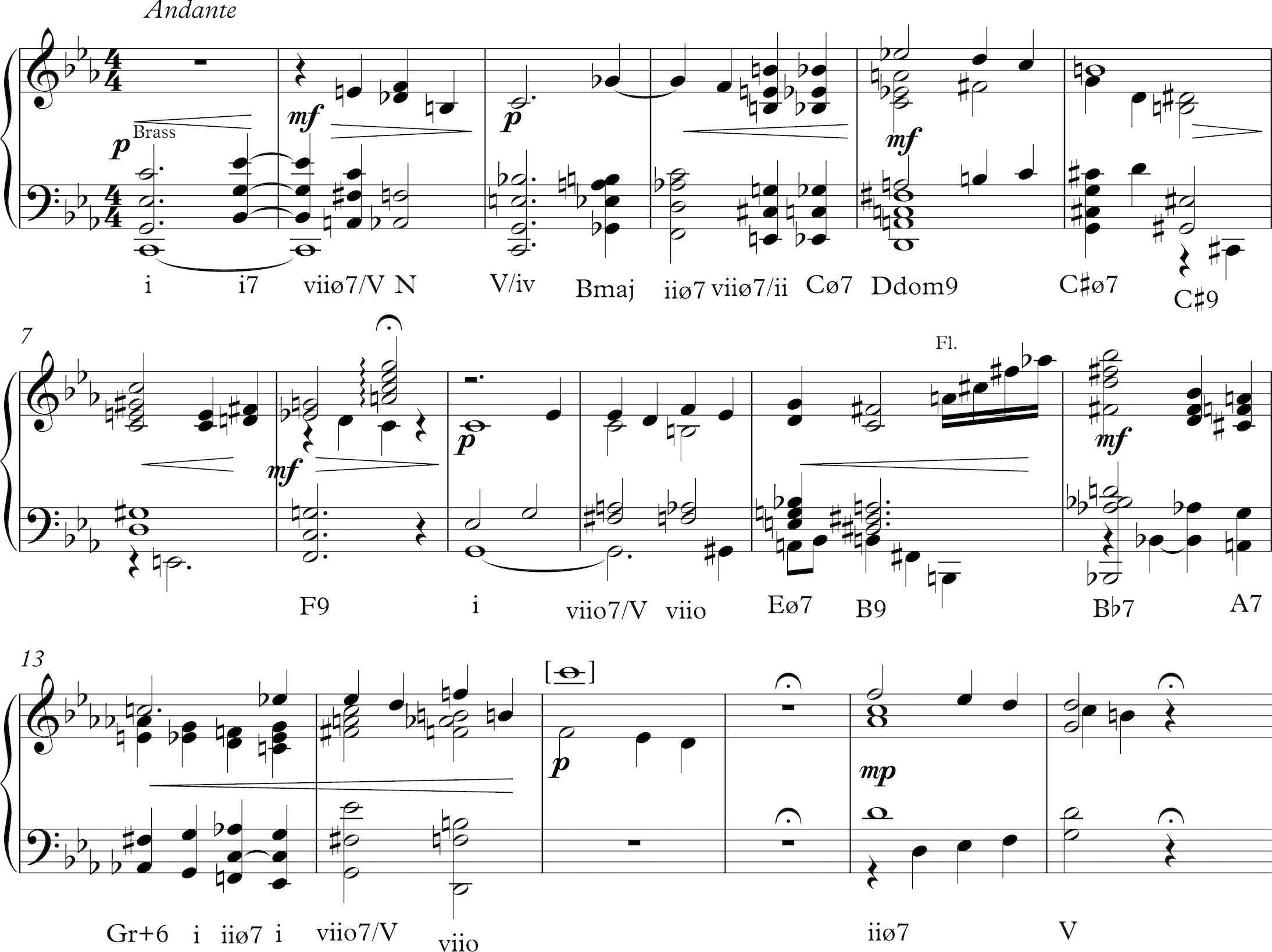

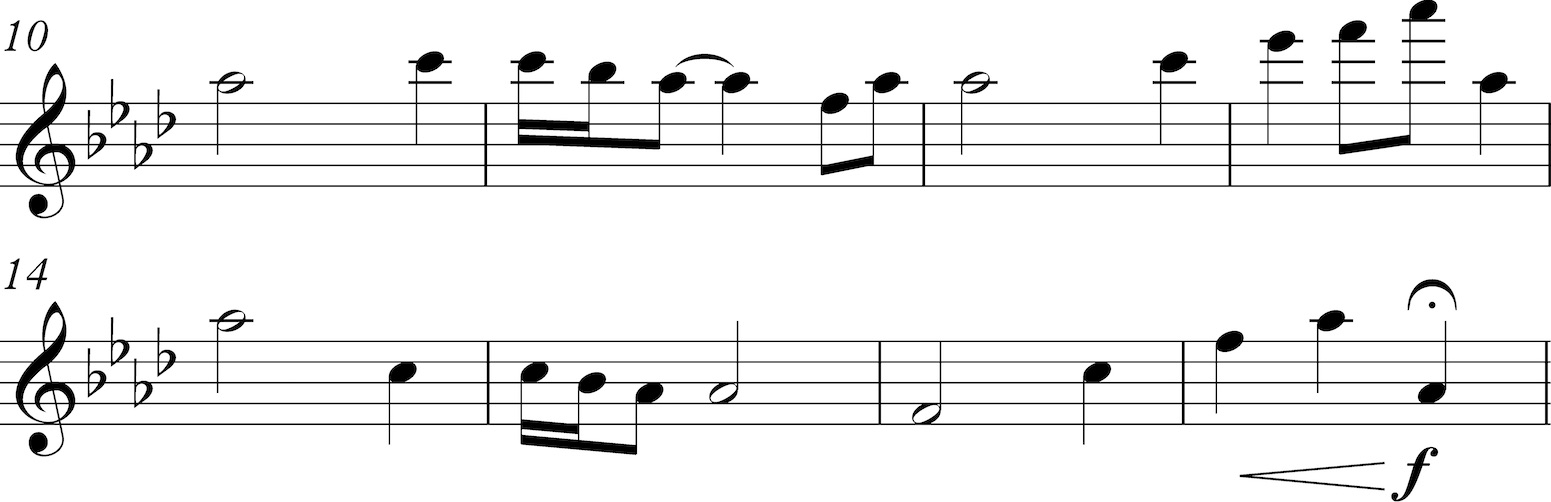

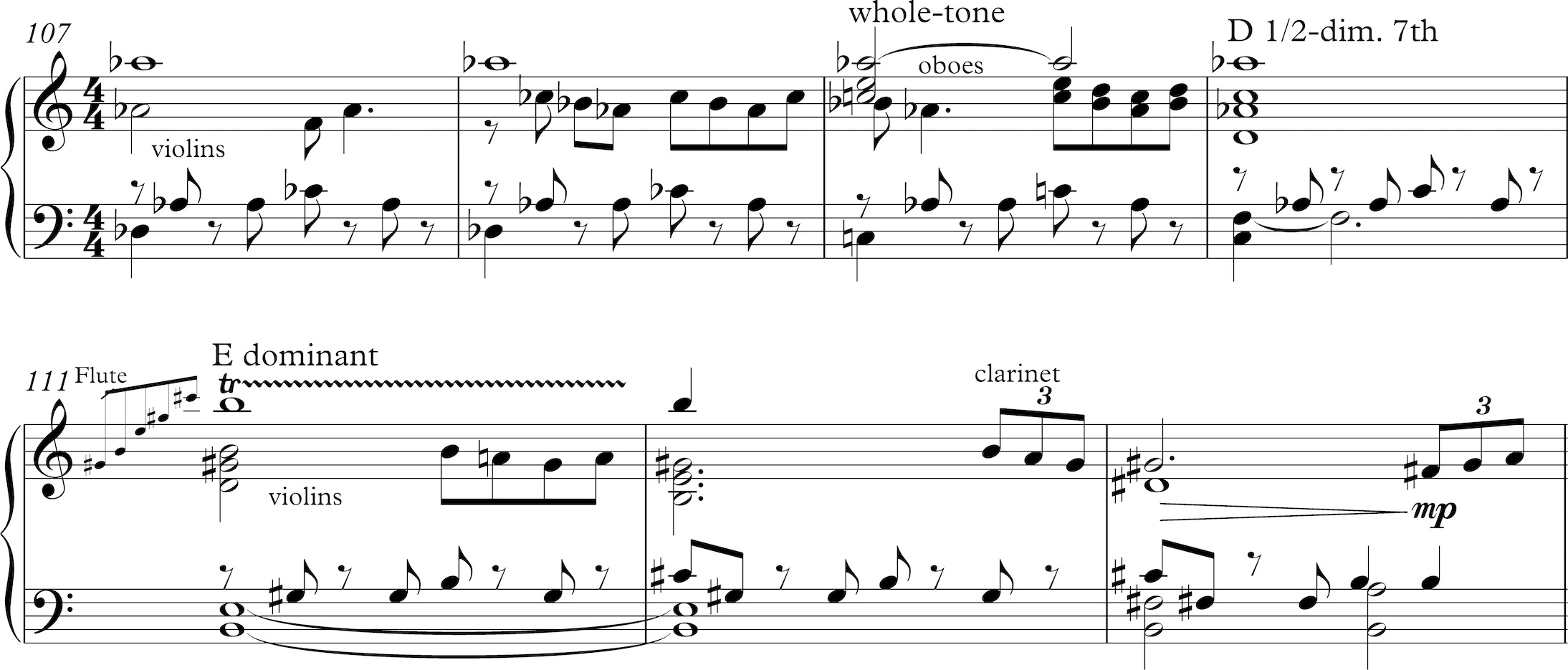

That dirge-like introduction is the most dissonant passage in the entire symphony, an eighteen-measure meditation darker in mood than the rest of the work, but which will be referred to briefly at the end of the first and fourth movements. Nominally it is in brooding C minor, but so full of unresolved half-diminished seventh chords, major and minor dominant ninths, and whole-tone chords that it becomes virtually atonal, touching back on C minor at mm. 9 and 13 and ending on a hesitant and incomplete ii-V in the home key. The introduction's thematic connections to the movement's themes are subtle. One is that the first phrase's rise to Eb and the second's rise to Gb have some parallel in the second theme itself, which, although otherwise in Eb pentatonic includes a bluesy Gb before it cadences. The other is the F dominant ninth chord on which the music pauses in m. 8; the second half of the second theme pauses on the same chord (see mm. 88 and 104). (The high C in m. 15 is audible on the recording, not present in the published score.)

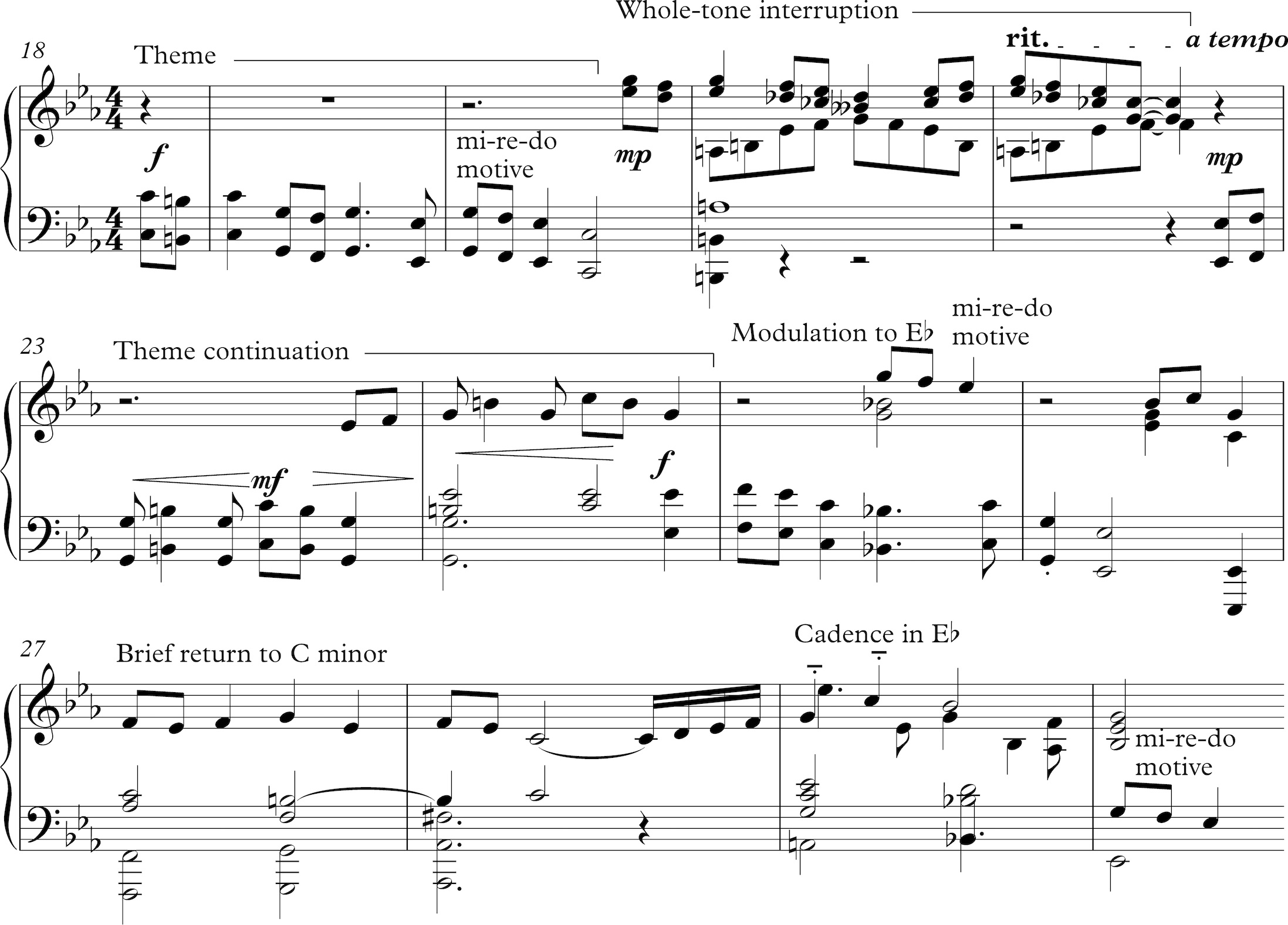

After this, the form of the movement is oddly asymmetrical: the first theme, in C minor, is ill-defined and little dwelt upon, while the second theme in Eb is developed at considerable length and stated in numerous variations. The first theme (one hesitates to call it the main theme) is a stark two-measure motive opening with a do-ti-do motive, almost like a fugue subject. This is immediately followed, though, by a two-measure interruption on a whole-tone scale with a ritardando at the end, which almost seems to mock the masculine phrase it follows, or at least creates ambiguity at the outset; I can only liken this jarring discontinuity to a man laying down the law and his wife rolling her eyes.

Another masculine phrase at m. 23 follows as if trying to continue the opening motive, repeated in canon in the next measure, and it emphasizes the B-natural in C minor, which will become an important feature in the recapitulation. From here the music quickly modulates to Eb major, which will prove to be the subordinate key, introduced here only seven measures into the exposition. As if to drive the point home, the music makes a last-ditch stand in C minor in mm. 27-28 before cadencing in Eb. So there. The three-note motive G-F-Eb appears foregrounded three times in this passage, and it will be central to the second theme at that pitch level; indeed a re-mi-do motive will recur in almost all the symphony's themes, often at this same pitch level, and should be regarded as a unifying factor. We should note that two eighth-notes on a strong beat followed by a longer note is a rhythmic motive pervasive in Price's music, a recognizable feature of her melodic style.

Measures 30 to 44 comprise a rather free-form transitional passage, with four measures of counterpoint in the general style of the first theme, some tremolo strings rushing monophonically through diminished chords, a flurry of chromatically sweeping whole-tone chords (mm. 39-40), some rather aimless counterpoint in mm. 41-43, and a series of chromatically parallel chords leading abruptly to the first anticipation of the second theme over a G drone.

What is also odd is that, after some more diminished chord flurries, this whole transitional passage in mm. 29-44 is essentially repeated in mm. 62-77 to arrive at the second theme itself at m. 78; to repeat the transitional theme area nearly verbatim before the second theme arrival is uncommon in sonata form, to say the least.

The entire remainder of the exposition, mm. 78-132, is devoted to restatement and subtle variation of the second theme, all in Eb major with only a modicum of chromatic inflections. The second theme, then, takes up almost half the exposition:

Introduction -- mm. 1-18: 18 mm.

First theme -- mm. 19-30: 12 mm.

Transition -- mm. 31-77: 47 mm.

Second theme -- mm. 78-132: 54 mm.

The theme also has an eight-measure extension, the first four bars vague as to melody but pausing on an F dominant ninth chord, the last four bars seeming to continue the melody and bring it to a close.

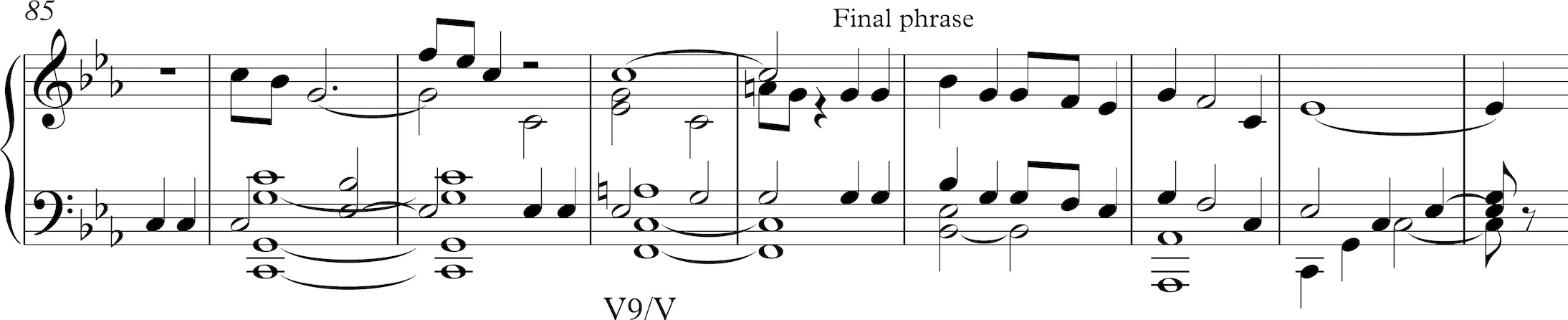

In mm. 78-109 the second theme and its extension phrase are played twice, with the strings taking the melody the first time and starting out in the woodwinds the second time, reaching a seemingly full close with the harp arpeggios in mm. 108-109.

The remainder of the exposition is a kind of closing theme section, but entirely colored by the second theme. Measures 110-119 are a self-contained phrase beginning and ending in Eb, but modulating through the circle of fifths to G before a ii-V-I in Eb.

Even after this restful close the next phrase in mm. 120-132 lingers in Eb over pentatonic motives from the second theme, finally introducing a B-natural to suggest a whole-tone coloration, but leading to a diminished seventh on B.

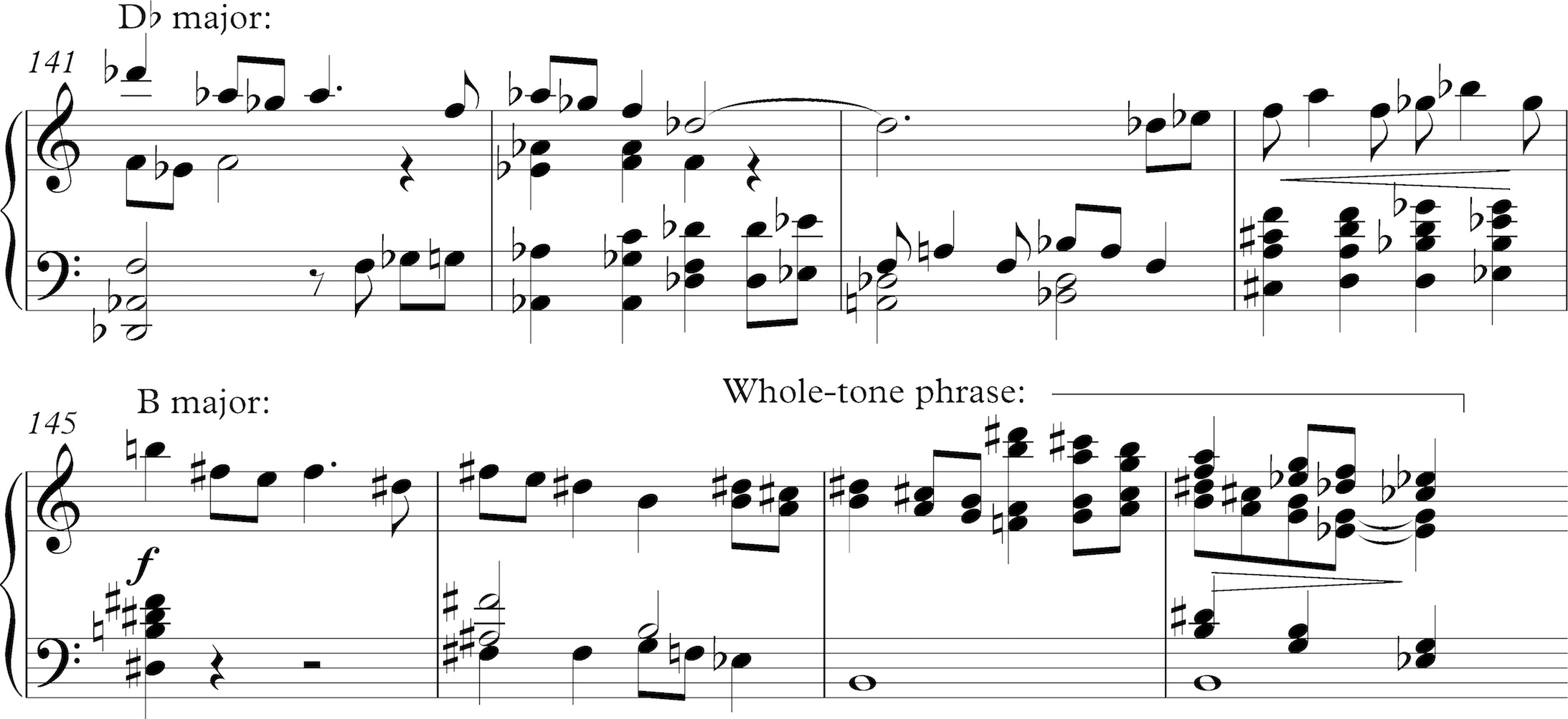

Though this sets up the listener to expect C minor again, the development (mm. 133-168) begins with the first theme in D. Measures 133-151 develop the first theme, whose opening notes appear in D major, then F, then the first three notes on F#, B, A, and G over a modulating progression. At the upbeat to m. 141 a full statement off the theme seems to arrive in Db major, with the whole-tone interruption phrase omitted; the theme is then stated in B major, with the whole-tone phrase inserted back in at mm. 147-148.

Measures 152-163 bring back ideas from the transitional section at various levels of transposition. A chromatic line in tremolo octaves in the strings (mm. 164-168) brings us rather precipitously to the recapitulation.

From m. 169 to 193 the recapitulation follows the exposition very closely. At m. 194, however, in place of the anticipation of the second theme as before, the second theme appears in C minor, transposed and transformed into the minor tonic key.

At m. 210 the music pauses on a V9/V (a chord that featured in the second theme's second phrase), and the harp gives a solo arpeggio on that chord.

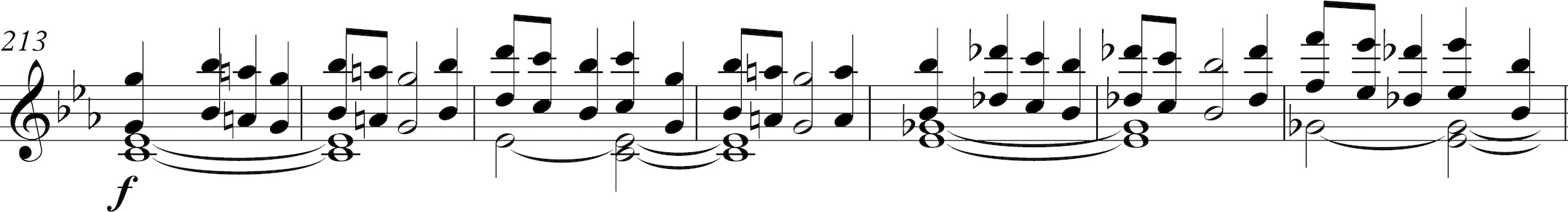

Measure 213 begins a lengthy coda bringing back all the previous ideas. The first is a variation of the second theme's opening idea, emphasizing the mi-re-do motive.

This climaxes as the mi-re-do moves up by half-steps over whole tone chords. A grand pause ensues, after which the orchestra states four dominant major ninth chords (mm. 223-229), over which the strings spin a couple of wandering lines, on a jazzy progression of Bb, E-natural, Eb, and Ab, this last being the blues chord that comes before the end of the second theme. The coda's variation theme resumes, climbing by minor thirds and breaking abruptly into a brief reminiscence of the introduction (mm. 233-237). This dying away, the orchestra breaks into a last fortissimo memory of the fugue-like first theme (m. 238), which descends to a series of dissonant chords over a low C pedal point. Curiously, before the final crashing chord the quiet major thirds in a whole-tone scale from m. 21, which seem to mock the masculine first theme, reappear - a gesture that in this dramatic context can only be heard as pointedly sardonic. The following chart of the movement should give an idea of what a centraL position the second theme occupies within the movement.

In the 19th century it was common to speak of a symphony's first theme as masculine (aggressive) and the second (more relaxed) as feminine; if that framework is accepted, it seems that Price concentrated far more on her feminine theme in the exposition, giving it a bitter and angry tone in the recapitulation.

Second movement

The second movement contains three clear themes. The first is stated at the outset by the oboe, and it appears at mm. 1, 18, 52, 111, and 126, always in the key of Ab. Except for one note (a G), the theme is pentatonic on Ab-Bb-C-Eb-F.

This theme has a continuing, likewise pentatonic phrase that separates statements of its main melody at mm. 10 and 103.

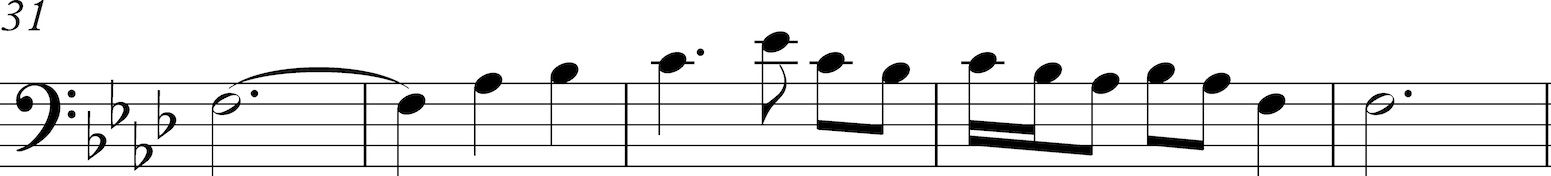

The second theme is stated monophonically, the first two times in the solo bassoon at mm. 31 and 38, then third time in octave winds and then orchestral tutti at mm. 45 and 49, always in F minor.

The third theme is the basis of a contrasting middle section in the key of G. It starts at m. 61 and is restated at m. 81. This theme is not self-contained, and wanders into whole-tone harmonies somewhat differently in the two statements.

Thus, labeling the themes A, A' (the first theme's second phrase), B, and C , the movement has a simple and clear thematic form of AA'ABBBBACCAA'AA. Leaving out the melodic repetitions, this could be more simply rendered as ABACA in the keys of Ab-f-Ab-G-Ab.

One might note that all these themes except the first emphasize a motive of two descending whole-steps, mi-re-do, which was also the link between the first-movement themes.

The themes, simple and diatonic as they are, are often separated by passages of more complex, whole-tone-tinged passages, as can be shown in a more detailed precis:

mm. 1-9 -- A

mm. 10-15 -- A'

mm. 16-17 ------ whole-tone material

mm. 18-22 -- A

mm. 23-24 ----- whole-tone material

m. 25 -- momentary return to A

mm. 26-30 ----- whole-tone materialmm. 31-35 -- B

mm. 36-37 ----- whole-tone material

mm. 38-44 -- B

mm. 45-48 -- B

mm. 49-51 -- Bmm. 52-59 -- A

m. 60 ----- whole-tone materialmm. 61-68 -- C

mm. 69-72 ----- whole-tone material

mm. 73-80 ----- chromatic transition

mm. 81-86 -- C

mm. 87-88 ----- whole-tone material

mm. 89-95 ----- chromatic transitionmm. 94-102 -- A

mm. 103-107 -- A'

mm. 108-109 ----- whole-tone material

mm. 110-115 -- A

mm. 116-121 ----- whole-tone material

mm. 122-125 -- A continuation

mm. 126-131 -- A

mm. 132-140 ----- coda resolving Db7 to AbThe A' melody, both times it is heard, harmonizes the end of its pentatonic tune with mostly dominant ninths (and one half-diminished ninth) leading to a lush, Debussyan Gb9 before proceeding again in Ab; the passage is repeated at m. 108-109.

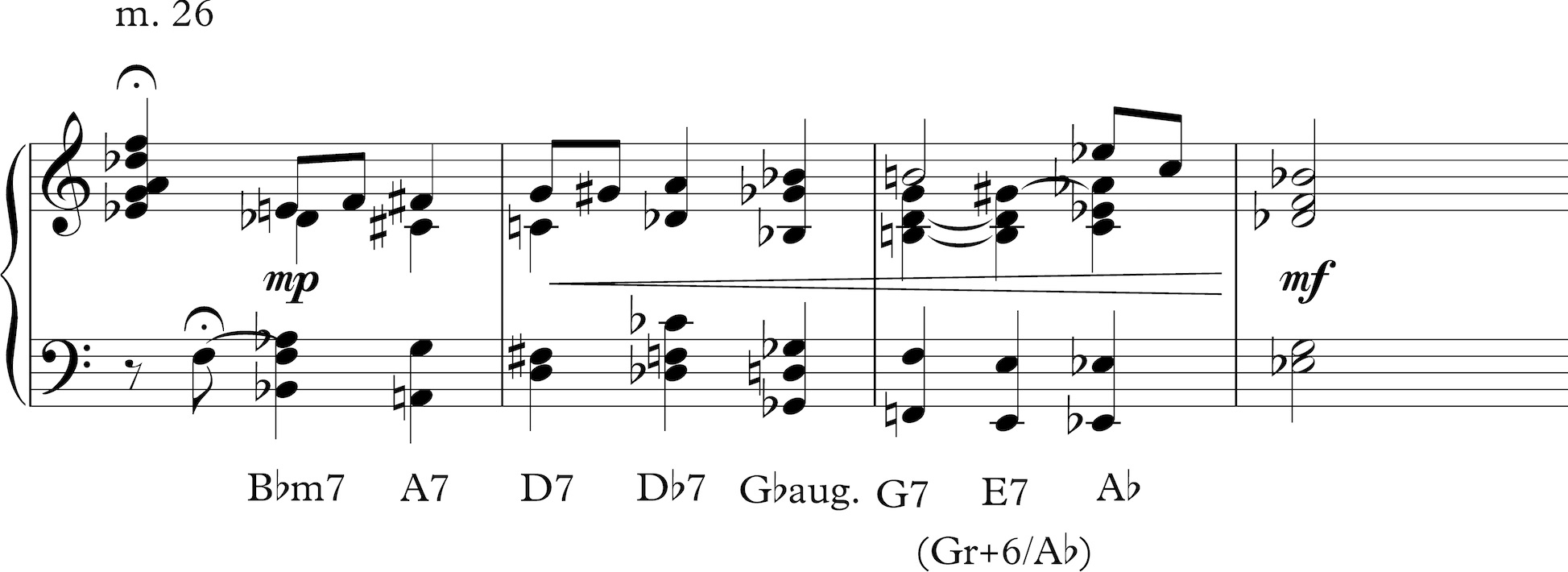

This could be redolent of jazz or impressionism, but the passage that ends the first A section (followed by a C7 leading to the second theme in f) seems more specifically jazzy with its mix of root movements by fifths and tritone substitutions (though the G7 moving chromatically to E7 which becomes the German sixth of Ab is very familiar from Brahms).

The first statements of the second and third themes are both followed by quiet passages of whole-tone thirds.

The movement's final cadence in its brief coda resolves a dominant chord on Db to Ab, a specifically bluesy touch that will be soon echoed in the following scherzo. Overall, the second movement has a pastoral quality reminiscent of Dvorak's slow movements, extremely tonally stable - no theme is ever transposed from its original key - but set off by recurring ambiguous moments of jazz and whole-tone harmony.

Third movement: Juba

Fast section

A section

Main theme in Eb -- mm. 1-16

Modulating development -- mm. 17-28

Main theme recap in Eb -- mm. 29-44

Second theme in G -- mm. 45-60

Second theme recap in G -- mm. 61-76

Main theme recap in Eb -- mm. 77-92Slower section

Blues theme in Ab -- mm. 93-106

Second blues theme, modulating -- mm. 107-114Fast section

Main theme development in A -- mm. 115-130

Main theme development in A repeated -- mm. 131-146Transition F > Ab -- mm. 147-150

Slower section

Blues section repeat in Ab -- mm. 151-160

Diminished seventh transition -- mm. 161-164Fast section

Main theme in Eb -- mm. 165-179

Transition -- mm. 180-184

Coda based on main theme in Eb -- mm. 185-195Again, the third-movement scherzo is titled "Juba," which is the name attached to a hand-clapping and body-slapping dance performed by slaves in the pre-Civil War American South. Supposed to have descended from an African dance, it was widely practiced after enslaved Africans were forbidden to use drums, which had communicative properties; tap dancing is believed to have evolved from it. The association gives Price leeway to explore a wide range of interlocking syncopations among different lines in the orchestra. This is a scherzo form with a couple of twists to it. In terms of tempos, it is an ABABA - fast-slow-fast-slow-fast. However, the first fast section has a secondary theme played twice in G, making this first section an ABA. The slow section is a pair of blues melodies. The second fast section is something of a development of the main theme that was in Eb, now in the distant key of A major. Then the blues material comes back, somewhat varied. The final fast section contains some development of the main theme, and finishes as only a partial restatement of the main ssction.

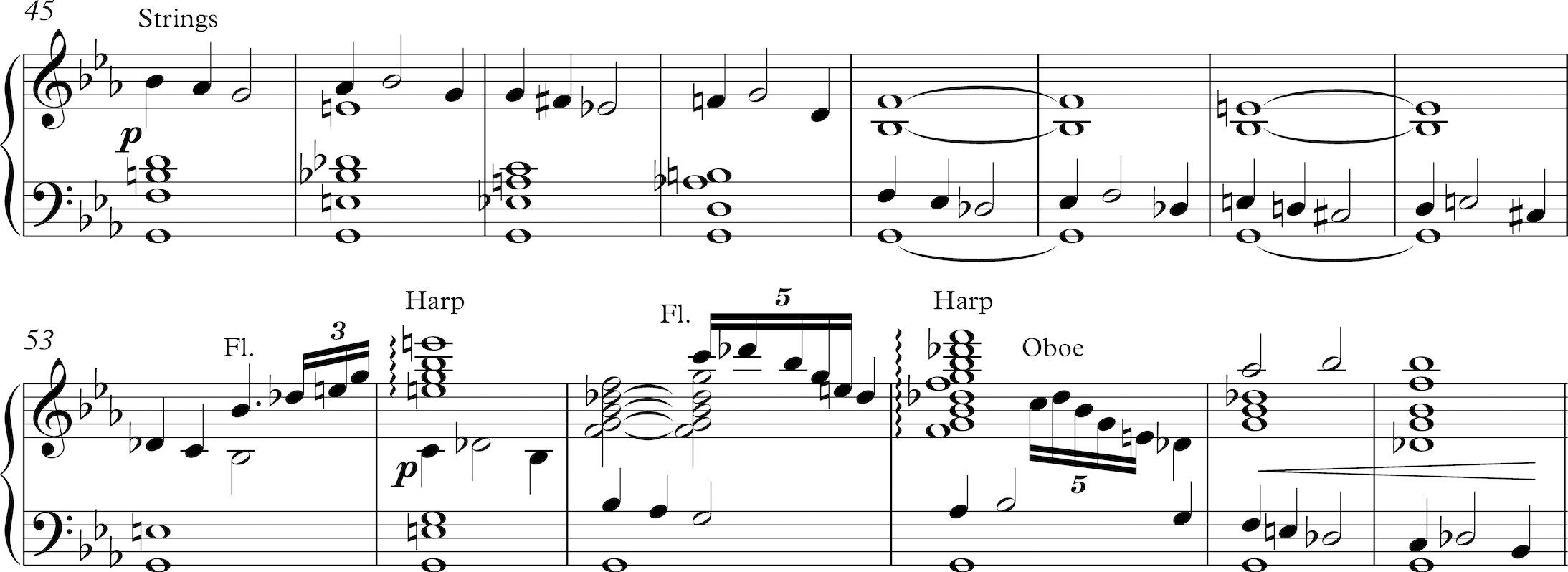

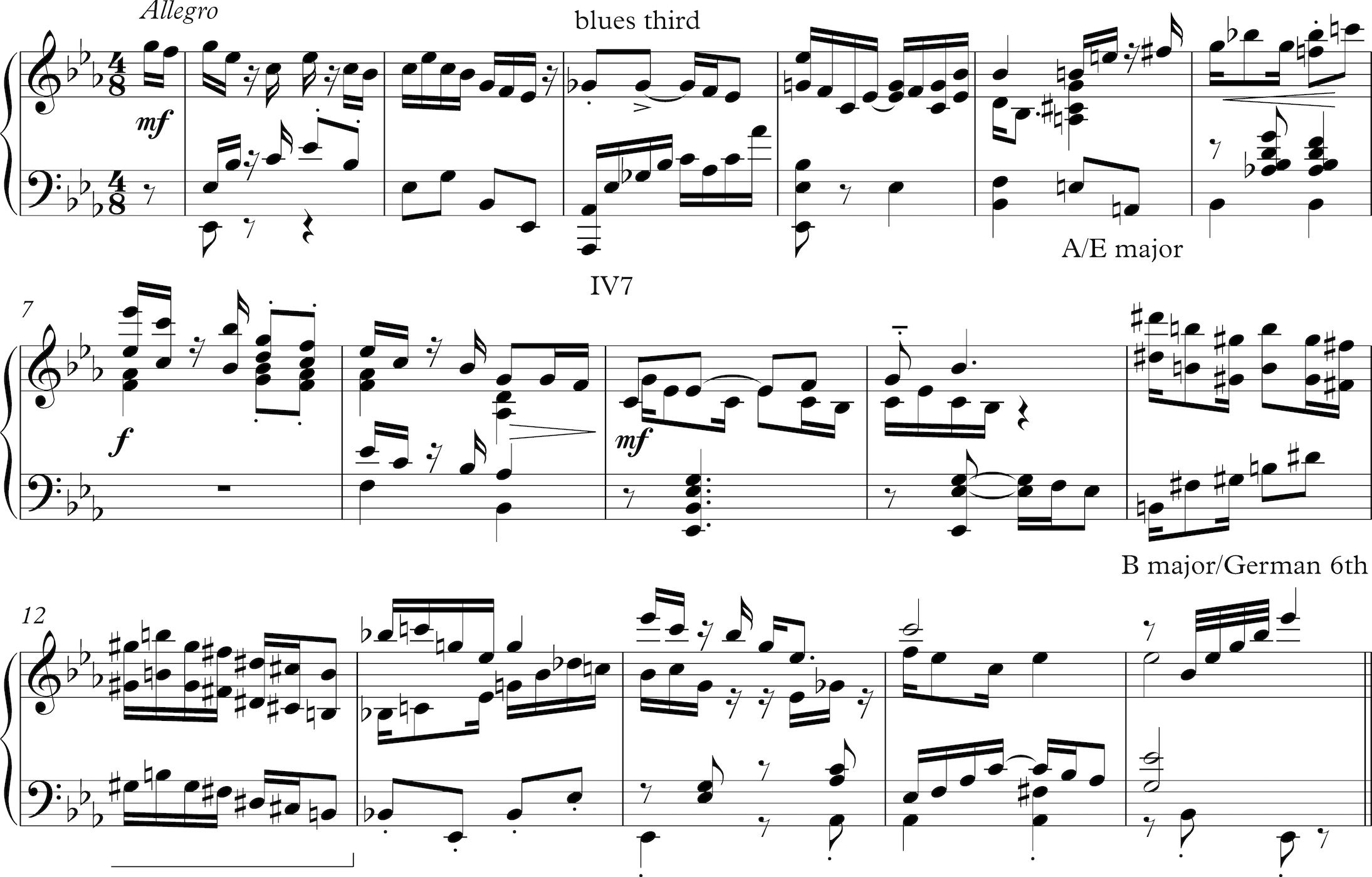

The first three notes (G-F-G) of Price's juba theme in Eb major seem to be repurposed from the first movement's first theme. Note the pervasive syncopation, the subdominant on Ab with its blues third on Gb, the quick shift to A/E major in m. 5, and the seeming abrupt modulation to B major in mm. 11-12, though that triad is actually the German sixth of Eb, and slides back into the tonic key smoothly. These features appear at every recurrence of the theme. One will note in m. 2 the G-F-Eb motive which was the common link between the two themes of the first movement - and at the same pitch level.

Measures 17-28 are a modulating interlude between the main theme's first two statements. Twice music of a continuing syncopated character jump from Eb to Gb, then passes through a passage on the Eb whole-tone scale (mm. 25-26), then rises through chords of Bb-Eb-Ab to start the theme over in Eb.

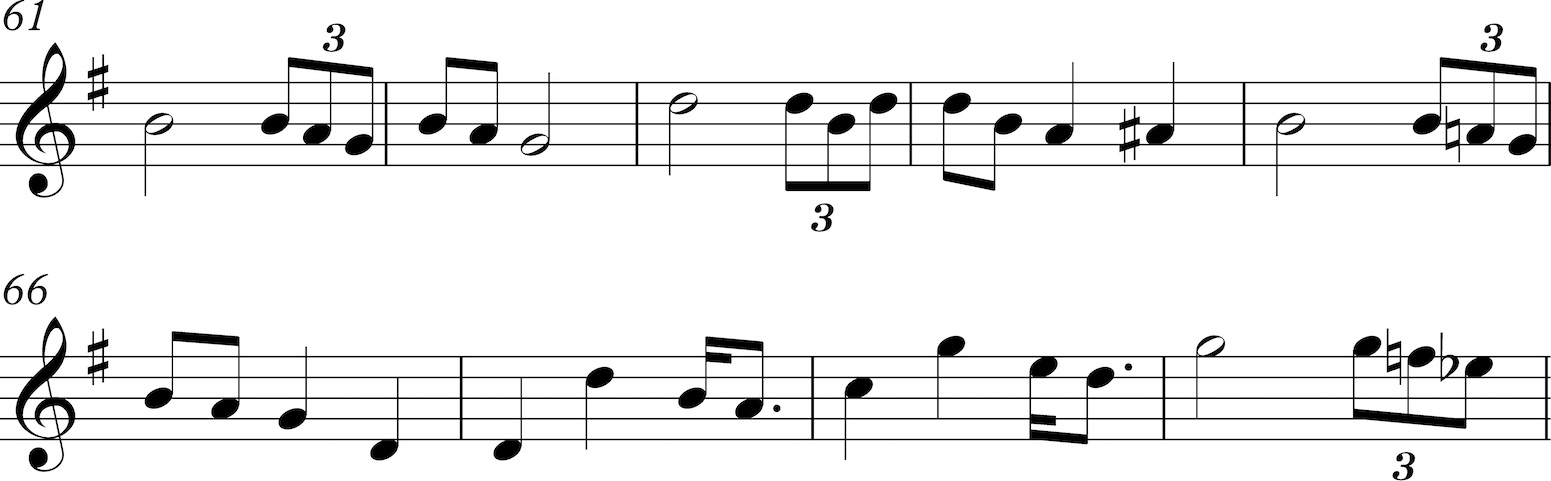

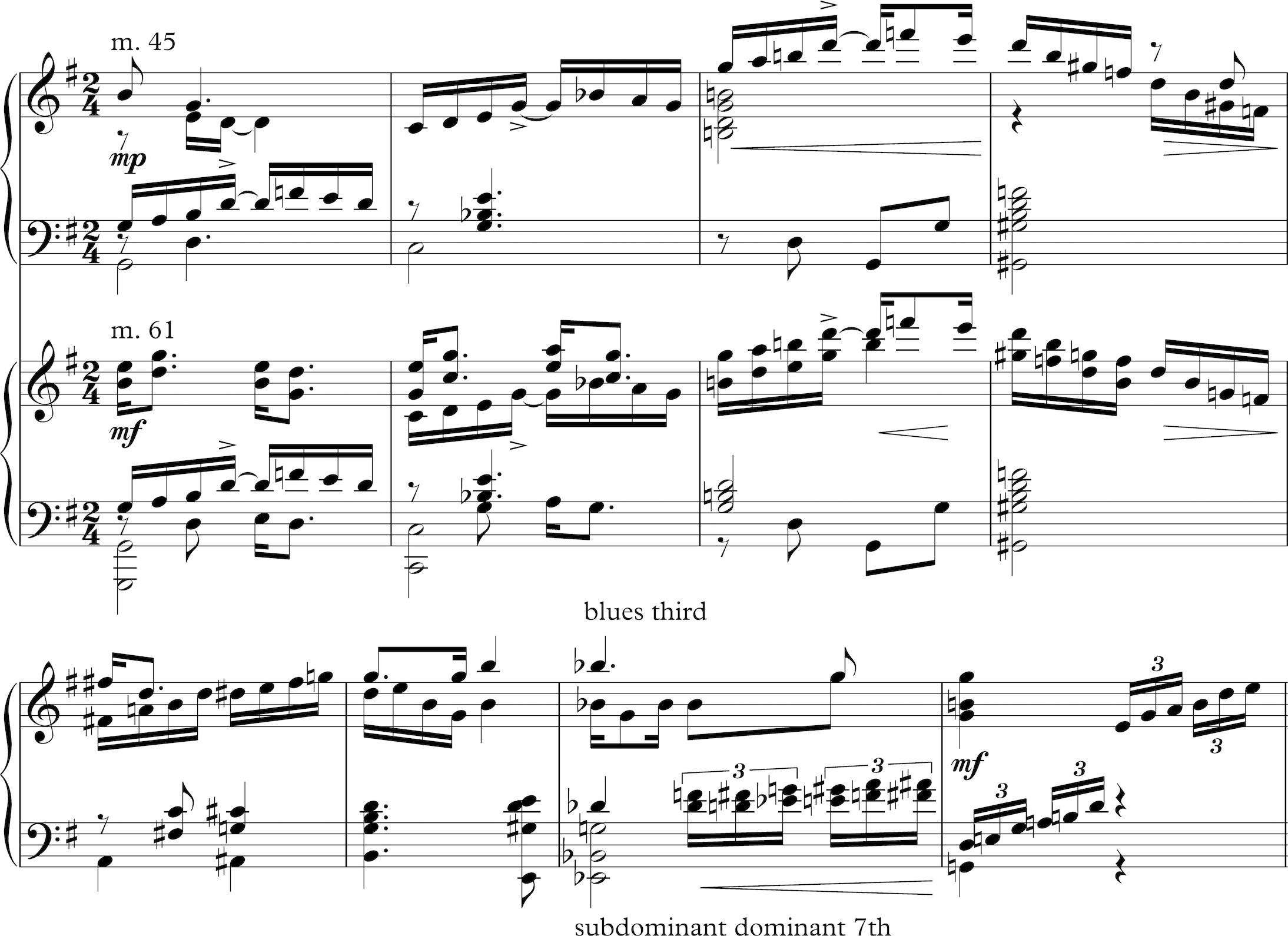

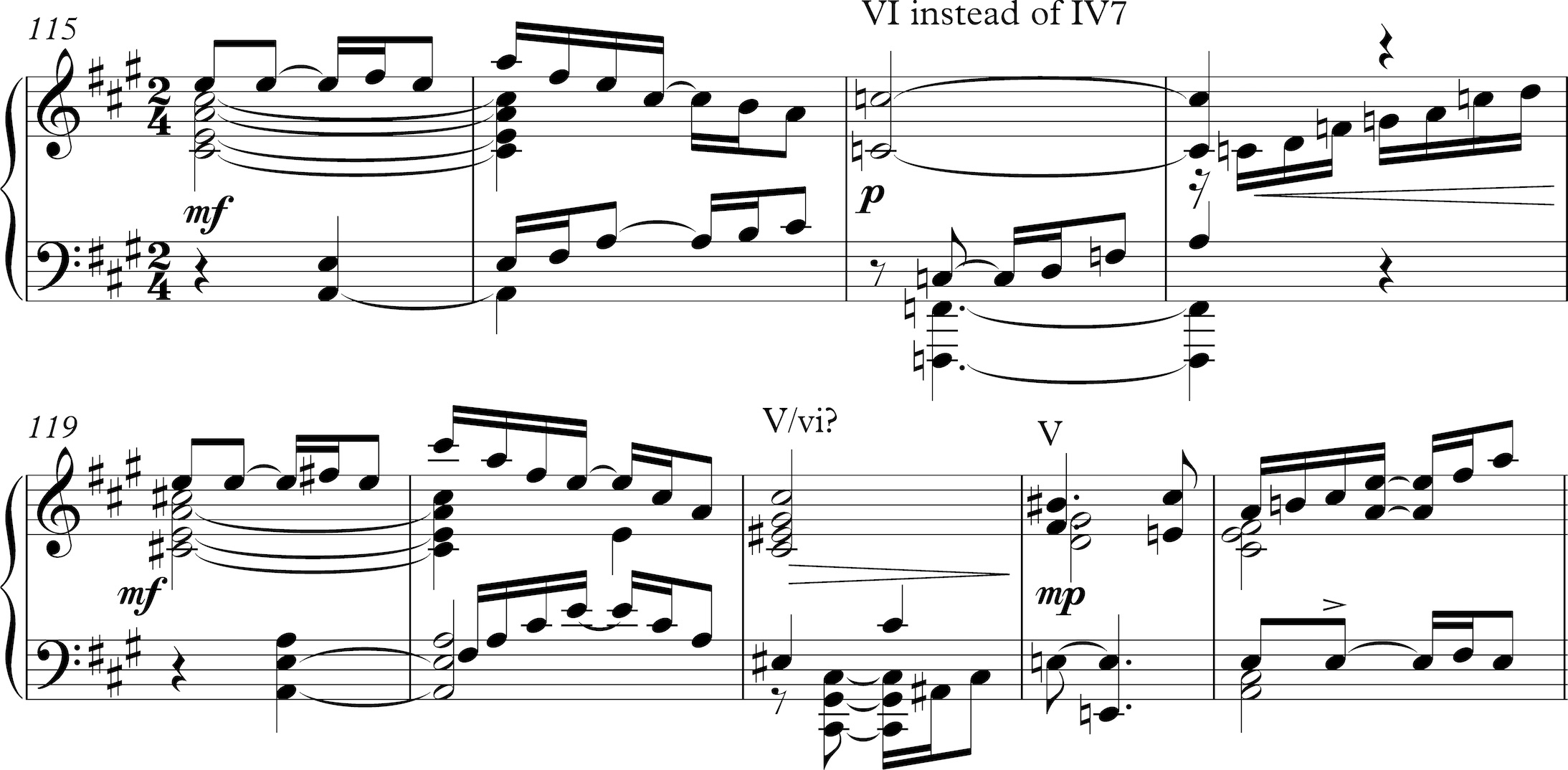

After the main theme's return, mm. 45-76 comprise two statements of a second theme in G major (mm. 45-60 and 61-76) with a decidedly ragtime nature. Comparison of the two versions shows how the first two measures of the theme are lightly disguised the second time, so that the listener isn't immediately aware that the theme is repeating. Note, as in the main theme, the blues third harmonized by a dominant chord on the subdominant at mm. 51 and 67.

This is sophisticated ragtime indeed, as the music feints through a series of chords on Ab, C7, and F7 in mm. 56-57 before returning to the G-major tonality at m. 58 (and similarly at mm. 72-73). The subsequent joyous return of the main theme in mm. 77-92 breaks into full-scale stride piano style, with a big oom-pah bass on the brass and lower strings.

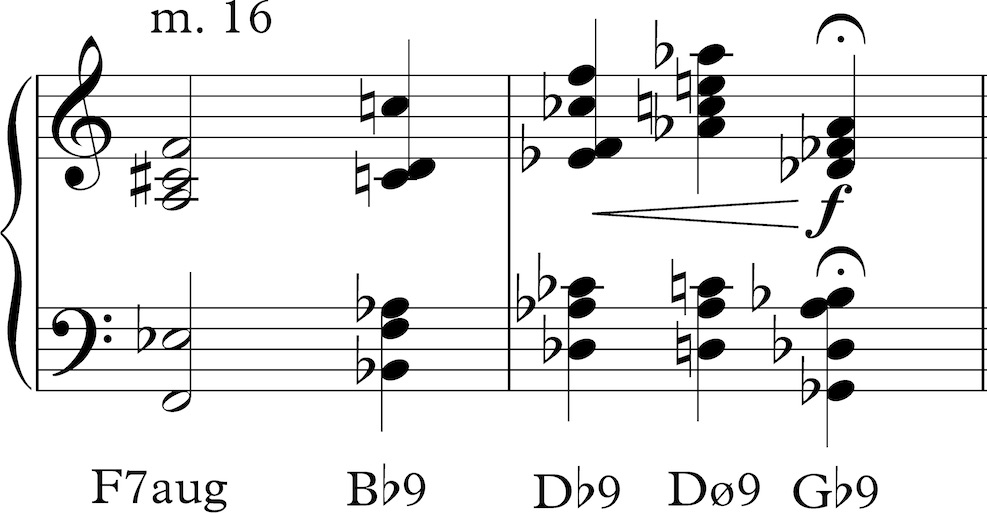

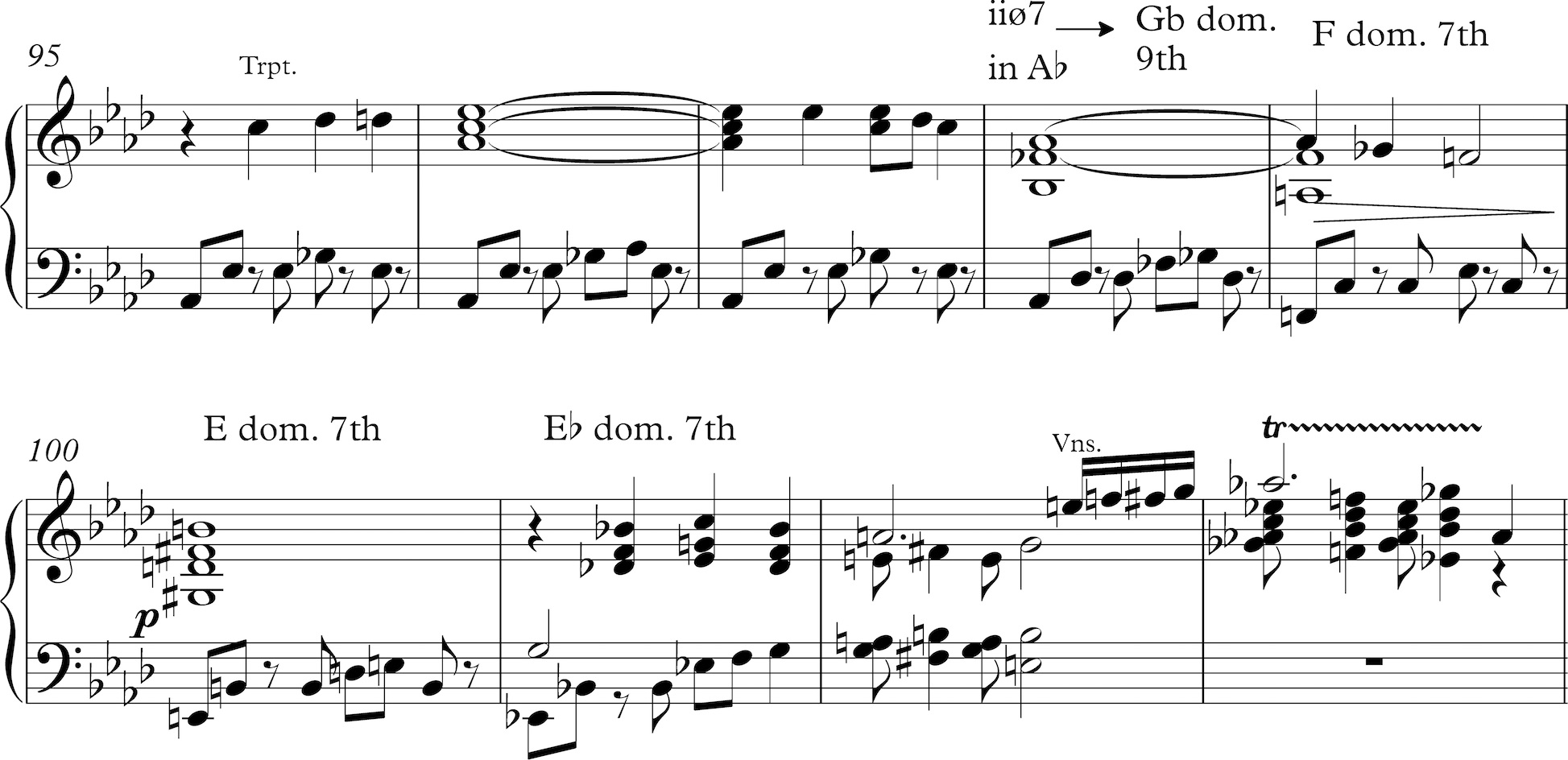

The trio of this scherzo (mm. 93-114, returning at 151-160) is a languid tango starting with a leisurely melody in the trumpet. Here Price's harmonic sense is delightfully sly and jazz-informed. Over the tango ostinato the tune turns down to a half-diminished seventh chord on ii - a predictable blues event - but in mid-measure (m. 98) the ostinato adds a Gb to turn it into a dominant major ninth on that root, and the line that we expected to go back to I or V of Ab starts modulating, slipping down another half-step though F and E to Eb. Even then at m. 101 we've reached the dominant and expect a return to the tonic, but she continues playing with our expectations, moving next to a dominant on A-natural.

After some chromatic muddying of the waters, the second phrase starts in Db. It doesn't parallel the first, and becomes even dreamier, with the melody passed back and forth between the strings and woodwinds, almost seeming to disappear at times. But the bass line descends once again through half-steps, with a moment of whole-tone ambiguity at m. 109, after which the D half-diminished seventh moves to an E dominant by simply having the F and C slide down to E and B. This sets up a modulation to A for the next section. The tonality of the whole trio is as natural and satisfying as it is unpredictable, and considering how willing Price is to simply repeat a section verbatim where she wants, the amount of fluidity she put into this trio suggests an unusual amount of enjoyment she put into writing it.

Now, in mm. 115-146, Price writes a section based on the main theme but varied and a touch more abstract - and in A major, as far away as possible from the opening Eb major. This time the minor third scale degree (m. 117) is a little more portentously harmonized with a VI borrowed from the minor instead of IV7, and at m. 121 the V/vi chord makes us expect a modulation, but she cheerily voice-leads it back to a V7. This quasi-development section tends to be more tonally unstable than the theme itself, threatening to turn into a transition rather than a variation, but it manages to remain within A major, and is immediately repeated.

In mm. 147-150 the F major comes back, and a small transition brings us to an abbreviated and normalized reference to the trio. This time the blues tune behaves conventionally on the I, IV, and V chords until m. 161 where it is interrupted with a four-measure transition on a diminished seventh chord. This leads back to the main theme in all its glory, with a little more climactic decoration but in a somewhat abbreviated statement. In m. 177, instead of the B major arpeggios returning to Eb, they veer headily through tonalities on D, Ab, and C. Another diminished-seventh transition brings us to a final and rhythmically dislocated coda variation on the main theme (m. 185), with an unexpectedly quiet and coy ending - two staccato chords after a missed downbeat.

Fourth movement

Exposition -- mm. 1-44

Theme in c -- mm. 1-16

Transition VI-V/V -- mm. 17-21

Second theme in g -- mm. 22-37

Closing theme -- mm. 38-44Development -- mm. 45-93

Theme on A7 -- mm. 46-51

Theme on Eb -- mm. 52-57

Theme on Eb aug -- mm. 58-61

Modulations -- mm. 62-81

Dominant prep -- mm. 82-93Recapitulation -- mm. 94-128

Main theme in c -- mm. 94-109

Transition VI-V/V -- mm. 110-113

Second theme in c -- mm. 114-128Coda -- mm. 129-242

Development -- mm. 129-236

Reference to intro -- mm. 237-239

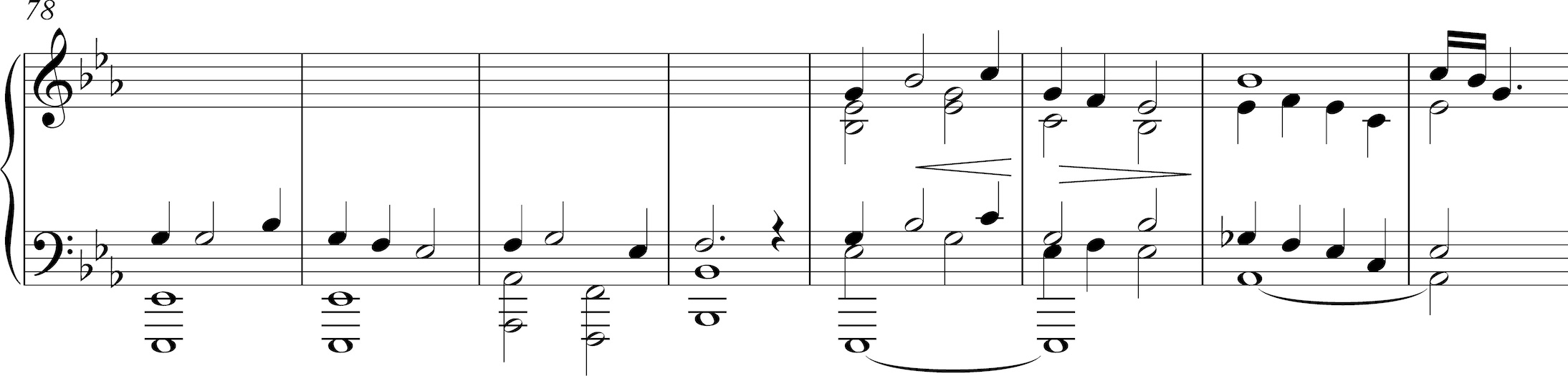

Tonic chords -- mm. 240-242The fourth movement (called "Scherzo Finale" despite the third movement's clear scherzo character) is even more unusual in form than the first. The first section modulates from C minor to G minor and is repeated verbatim, as though this is going to be a second sonata-allegro form. The non-modulating return of this passage at m. 94 does act as a recapitulation, but at m. 129 the music spirals into a wild orgy of free development more than a hundred measures long.

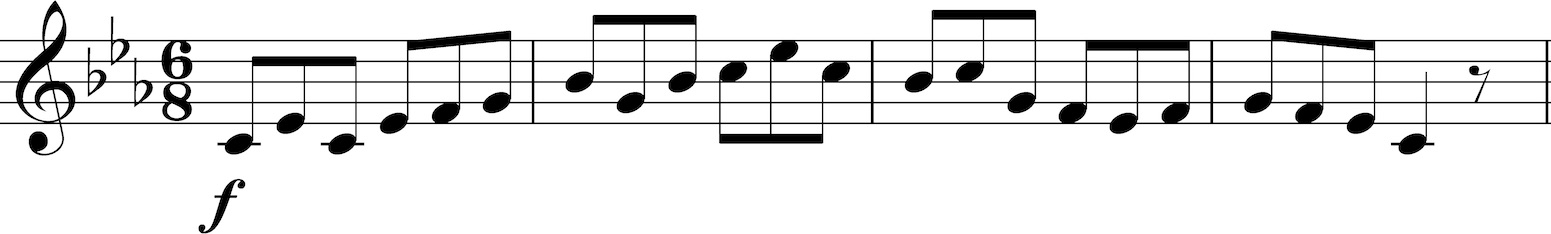

Like the final movements of the First and Fourth Symphonies, the movement is in 6/8 meter, here with a rollicking, Celtic-sounding theme in pentatonic minor, containing in its last measure the G-F-Eb motive that runs through the symphony.

In mm. 9-10 the theme starts to bend toward Eb major, but is quickly brought back; in measures 13-16 this happens again. The transition between tonalities is about as short as it can be in a symphony: in mm. 17-21 we have two measures of Ab dominant seventh figuration (the German sixth), then three of a D dominant seventh, and then we're in G minor. This subordinate-theme area is so similar to the main theme as to seem like a continuation, but we do get the new form of the theme (what I will call the theme motive) that will be most often developed afterward (here in the lower voice).

The movement is somewhat haunted by the B-naturals (raised seventh scale degree in minor) that had embittered the transposed repeat of the second theme in the first movement, where the theme now moved from Eb major to C minor is dissonated by the raised sevenths - evident in this example in the alternations between F# and F-natural. In this movement the two seventh scale degrees are more smoothly integrated, but the mood no less bitter for that.

The whirlwind momentum of eighth-notes relaxes a little in the closing theme area of mm. 38-44, and the exposition is repeated. The first development, mm. 45-93, can only be described as a series of modulations and dominant sevenths dotted with arrivals of the thematic motive: mm. 46-51: theme motive on an A dominant 7th mm. 52-57: theme motive (distorted) on Eb mm. 58-62: theme motive in the whole-tone scale with a G pedal mm. 63-66: theme motive on Ab modulating to B7 and e mm. 66-70: theme motive on a C dominant 7th mm. 71-76: counterpoint in E minor then major mm. 77-79: counterpoint on Eb dominant 7th mm. 80-81: quick modulations on Ab, F dominant, D dominant, Ab mm. 82-93: transition: grand dominant preparation in C minor in string octaves

In measures 94-113 the recapitulation follows the exposition closely, with more lines of counterpoint added. This time, the transition on Ab and D dominant sevenths (mm. 110-113) omits the final measure and plunges back into C minor. Measures 114-128 then parallel the second-theme part of the exposition, transposed into C minor.

From this point on, however, all normal expectations of sonata form are suspended. The last 114 measures of the piece - which we should refer to as the coda, I suppose - are entirely developmental in character, and constitute a phantasmagoria of ambiguous scales, expectant dominants, and recurring motives which I defy anyone to sum up in an intelligible sectional outline. Below I chart mm. 128-236 including only the harmonic and motivic material, which should be easy enough to follow with a recording. The theme motive appears on E (m. 131), on an Ab dominant (m. 137), varied on Db and Ab dominants (m. 144), in a whole-tone scale (m. 155), in C minor (m. 159), in Ab (m. 170), and a final C minor appearance at m. 211. The rollicking contrapuntal texture is increasingly interrupted by series of chords, first dotted quarters and later dotted half-notes. The music slows to a pause in mm. 176-178, as the motive's last four notes are developed independently, and again at m. 181; another pause comes at m. 210 just before the motive's final statement in C minor.

This is a chaos of development, a wild rambling in which the theme motive gradually becomes less common, the interruptive chords more frequent, but in which no overarching harmonic framework seems evident. At last, after the particularly dissonant chords of mm. 233-236, the music launches into a final (too brief?) quotation of the symphony's opening motto and chords, leading to a few last blasts of tonic C minor. It is as though the opening lament is given as the excuse, the source, of the aimless-seeming turmoil of the final development.

While the inner movements of this symphony are relatively conventional in form, the outer sonata-allegro movements are quite eccentric, almost impatiently so. The first and fourth movements are also marred by overuse of a late-romantic tic: the wandering streams of chromatic monophonic lines in the strings, in octaves or tremolo or both, that seem to fly from one thematic passage to another as though searching for a place to land; these don't occur as much in Price's First and Fourth symphonies. The second movement is charming, the third delightful in every measure. However, the conflicts between a simple Eb major and an anguished C minor can seem to harmonize the entire work into a unified gesture, as the G-F-Eb motive points to the underlying unity of the materials. Perhaps the perceived flaws and formal asymmetries are markers of the anger and resentment that hover on its periphery.

Copyright 2019 Kyle Gann

Return to American Symphonies

Return to the home page