James P. Johnson: Harlem Symphony (1932)

Analysis by Kyle Gann

All score reductions by the author

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 3.0 License."Authenticity" is a word one bandies about at one's risk these days, since abundant doubt has been cast on who is qualified to decide what is authentic in terms of whose music. Yet the Harlem Symphony of James P. Johnson (1894-1955) has long fascinated me as a jazzman's contribution to the classical repertoire. Many, many composers, both white (Aaron Copland, George Gershwin, Leonard Bernstein) and black (William Grant Still, Florence Price, William Dawson) have written orchestral works which introduced jazz and blues idioms into European conventions. But the Harlem Symphony stands out as a jazz and blues piece, by one of the outstanding stride pianists at the peak of his career, that fits its materials into classical forms without much compromising their character. Johnson was trained in classical music, of course, since in his youth classical music was virtually the only kind in which tuition could be found. And he follows the classical formulas - but almost perfunctorily, simply making the requisite key changes, never distorting the style he's most familiar with to put on classical airs. The result is a piece that fills out a classical architecture, but sounds honest, fun, unpretentious - and not divided in its allegiances.

My source for this analysis is the orchestral manuscript I found in the Jazz Institute Archive at Rutgers University. There are discrepancies between this score and the performance conducted by Marin Alsop on the Nimbus label, especially in the first movement. Arguably the score is improved by the changes made, but I don't know who is responsible for them.

First movement: Penn Station (Subway Ride)

Introduction -- mm. 1-8

Introduction to Train -- mm. 9-16Exposition -- mm. 17-74

First theme in Bb -- mm. 17-40

---- Transition -- mm. 41-45

Second theme in F -- mm. 46-74Development -- mm. 74-111

Transition ("Lady Shoppers") -- mm. 74-85

Second theme in D -- mm. 86-93

First theme in G -- mm. 94-101

---- Harmonic transition -- mm. 102-111Recapitulation (7th Ave. Promenade) -- mm. 112-152

First theme in Bb -- mm. 112-119

---- Transition -- mm. 120-129

Second theme in Bb -- mm. 130-140

---- Transition -- mm. 141-144

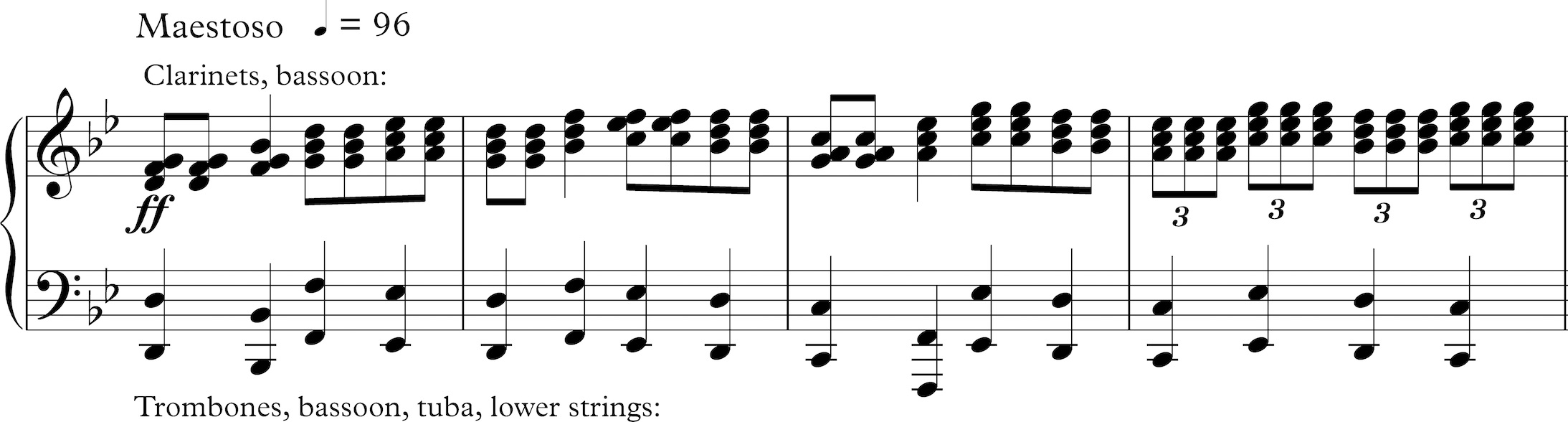

Recap of introduction -- mm. 145-152The first movement is titled "Penn Station" in the manuscript (though as "Subway Ride" on the recording), and has some descriptive titles marking certain sections to show what they are depicting. The first four pages Johnson evidently considered an introduction; they are labeled A through D, and the fifth page is marked as page 1. The piece opens with a grand, lumbering bass theme that will return at the end of the first movement.

Oddly, pages C and D (mm. 9-16) are omitted from the recording, and they do seem a little out of place. They are labeled "Train," and are clearly meant to evoke the subway train beginning to take off, partly (mm. 13-14) with a steady beat on a drum with wire brushes.

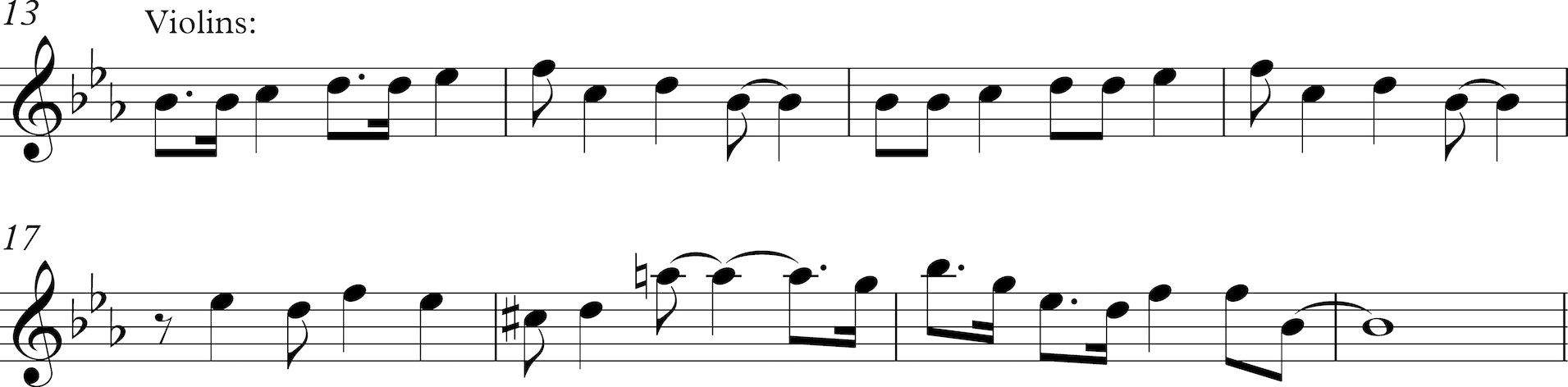

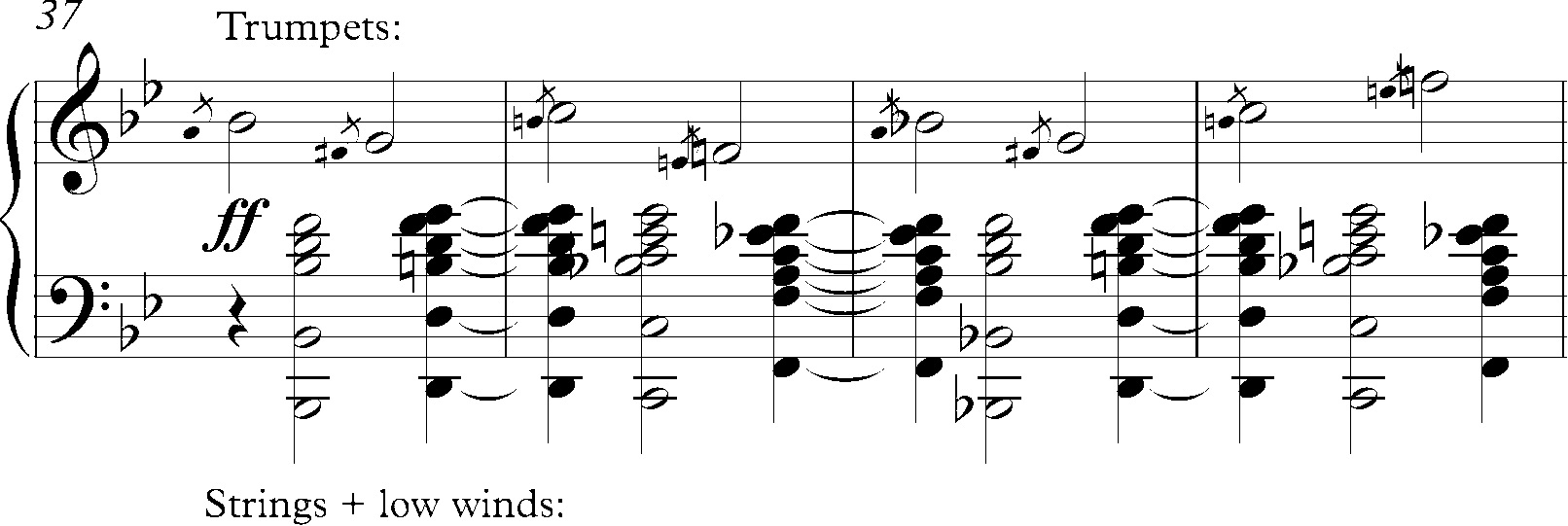

The first theme might be taken to be that played by just the strings in the following example, with their motive of thirds and fourths moving by half-steps - specifically, chromatic appoggiaturas moving to the chord tones of the harmony. However, the added wind notes above do contribute to the melody, and are difficult to separate out.

Remarkably, the first violins' melody employs ten of the twelve notes in the chromatic scale, despite the economy of notes and the simplicity of the harmony. The B section part of this theme is a horn solo accompanied by chords going around the circle of fifths, after which the first theme is repeated again, though this time with the flutes echoing similar eighth-note gestures. Oddly, the recording repeats both A and B sections, though the score does not call for it.

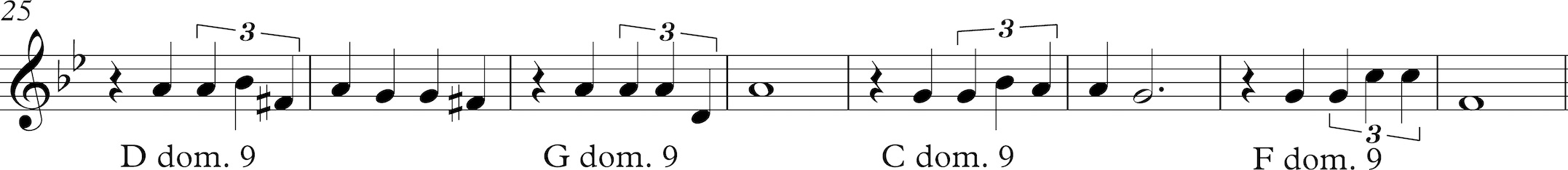

The transition from the first key area to the section is one of the briefest and most functional since the mid-eighteenth century. A clarinet plays two phrases (mm. 41-44), the first arpeggiating I-V-I in D, the second V-V7-V/IV in C, and then we're in F major.

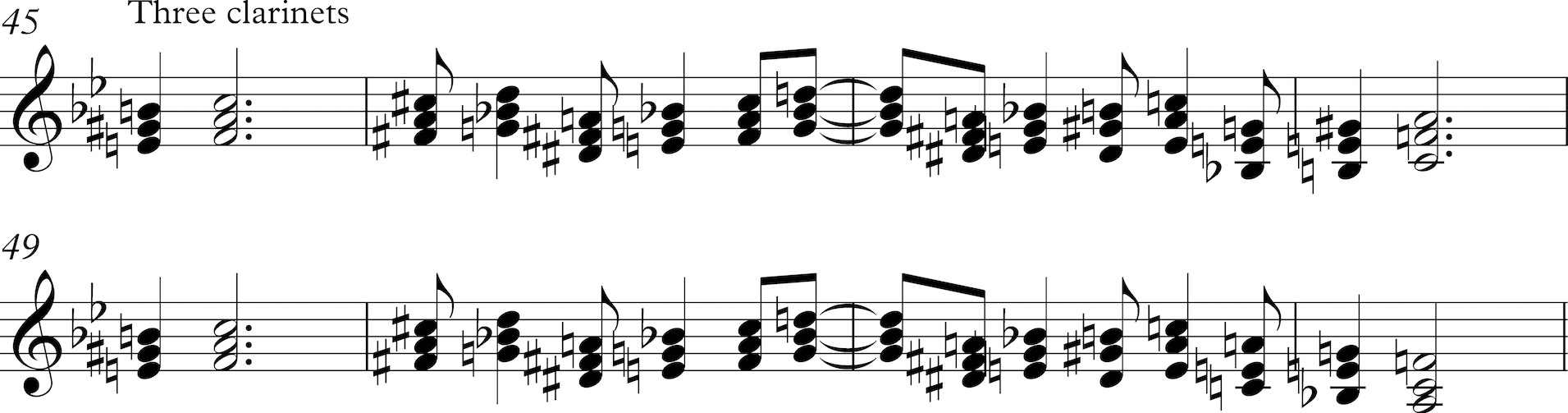

The derivation of the second theme from the first is impressively clever. Like the first theme, this one precedes almost every triad in the harmony with an appoggiatura chord a half-step lower, but the rhythm is sped up and irresistibly syncopated. The first theme's initial motive is an eighth-note moving to the tonic: here it becomes a quarter-note moving to the dominant scale degree. Also, the scoring for a chorus of clarinets is taken from jazz orchestration - one can hardly imagine a classical composer announcing a new theme in parallel chords by three of the same instrument.

Like the main theme, this subordinate one also has a middle verse after which it returns:

And I particularly admire that in the repeat of the second theme, Johnson changes one note to approach the cadence from a different half-step.

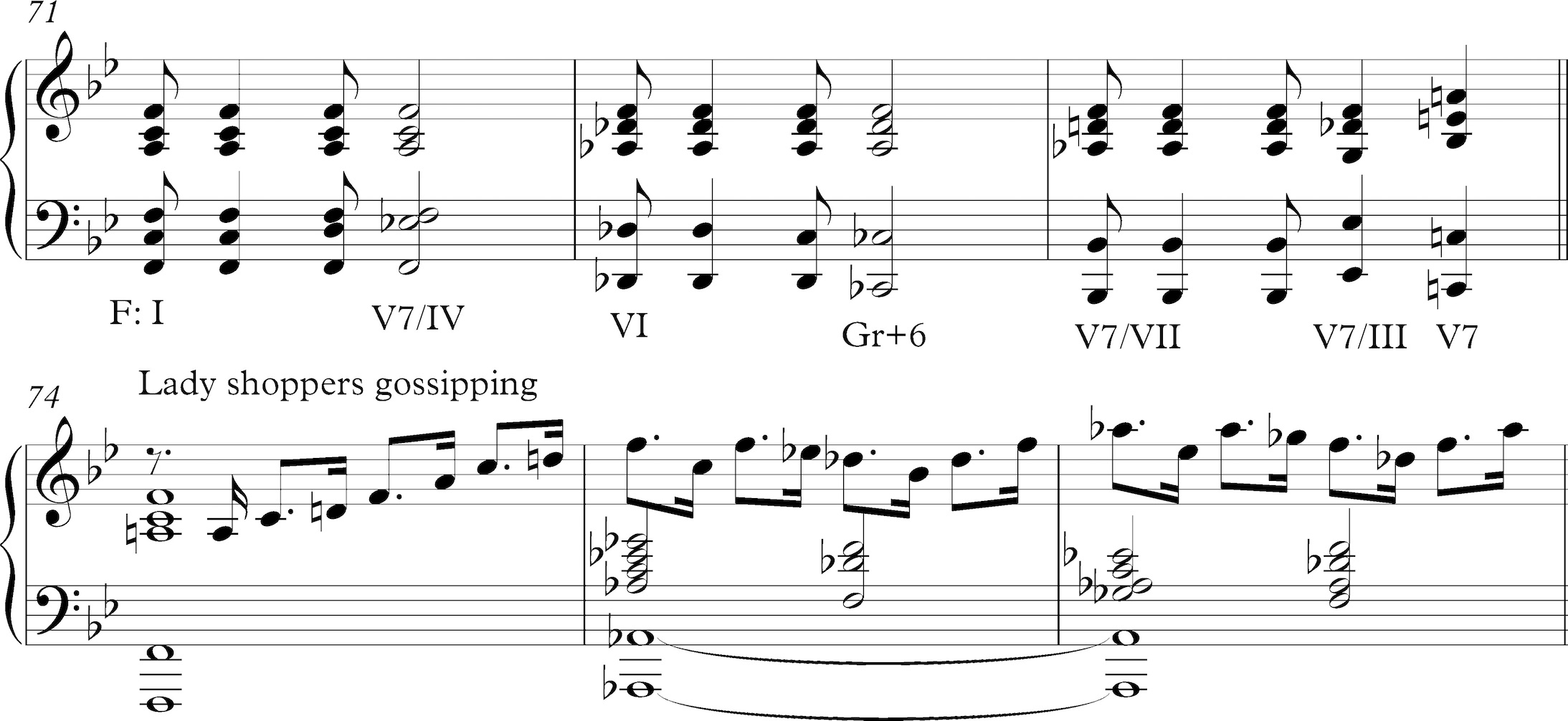

The repeat of the theme is immediately followed by a colorful chord progression bringing the exposition to a close in F. Clarinets and strings in dotted rhythms open the development with an immediate move to Db, the rhythm intended to convey a pictorial effect that Johnson labels "Lady Shoppers - gossiping."

One imagines the humor was better appreciated in 1932.

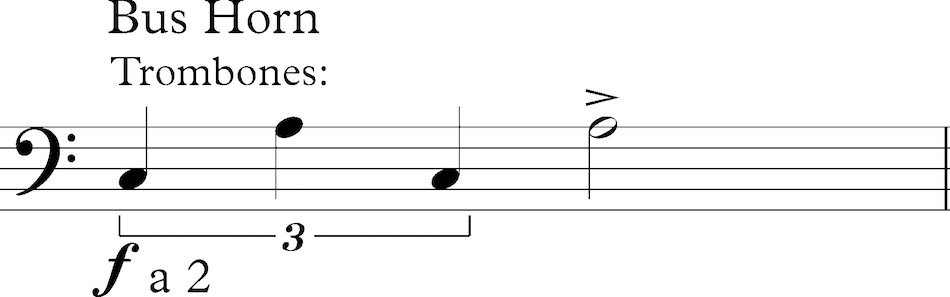

In mm. 75-85 a rhythmicized chord progression thick with tritones descending by half-step leads to a dominant pedal on A. The subordinate theme enters in the key of D now (mm. 86-93), poco piu mosso and with a countermelody soaring high above in the piccolo. Its final D chord becomes a dominant, and forthwith the first theme is stated in G (mm. 94-101), by the trumpets and trombones using cup mutes and the latter echoing the former. To end the development, the brass syncopate their way through a simple chord progression (Bb7-Eb, B7-E, C7-F, F7, mm. 102-111), pausing at the end for a wry figure in the trombones clearly labeled "Bus Horn."

The opening of the recapitulation is labeled "7th Ave Promenade." The first theme is played in Bb by the tutti orchestra (mm. 112-119). A tumultuous transition of syncopated dominant chords descending by half-steps, and marked Presto, acts as transition to the subordinate theme, now played in Bb and also tutti, the tempo marked "a tempo" and "slower" (mm. 130-140). A staccato piccolo line rings out above the orchestra. (Neither theme includes its middle section nor is repeated in the recap.) An expectant series of augmented triads then rises by half-step, and the opening introductory theme returns "grandioso" in the trombones to close the movement.

Second movement: Song of Harlem (April in Harlem)

Exposition -- mm. 1-59

First theme in Bb -- mm. 1-16

---- Transition -- mm. 17-23

Harlem Love Song in F -- mm. 24-55

---- Transition -- mm. 56-59Recapitulation -- mm. 60-119

First theme in Bb -- mm. 60-75

---- Transition -- mm. 76-84

Harlem Love Song in Bb -- mm. 85-115

Coda -- mm. 116-119Johnson's second movement is titled Song of Harlem in the manuscript, though on the recording it is called "April in Harlem" - probably a sly reference to the popular Vernon Duke song "April in Paris" that appeared the same year as the symphony. This is in a type of slow-movement form common in the 18th-century called sonata without development, meaning that the second theme of the exposition is transposed to the tonic in the recapitulation, though the two sections are not separated by a development section; Johnson clearly knew his classical repertoire.

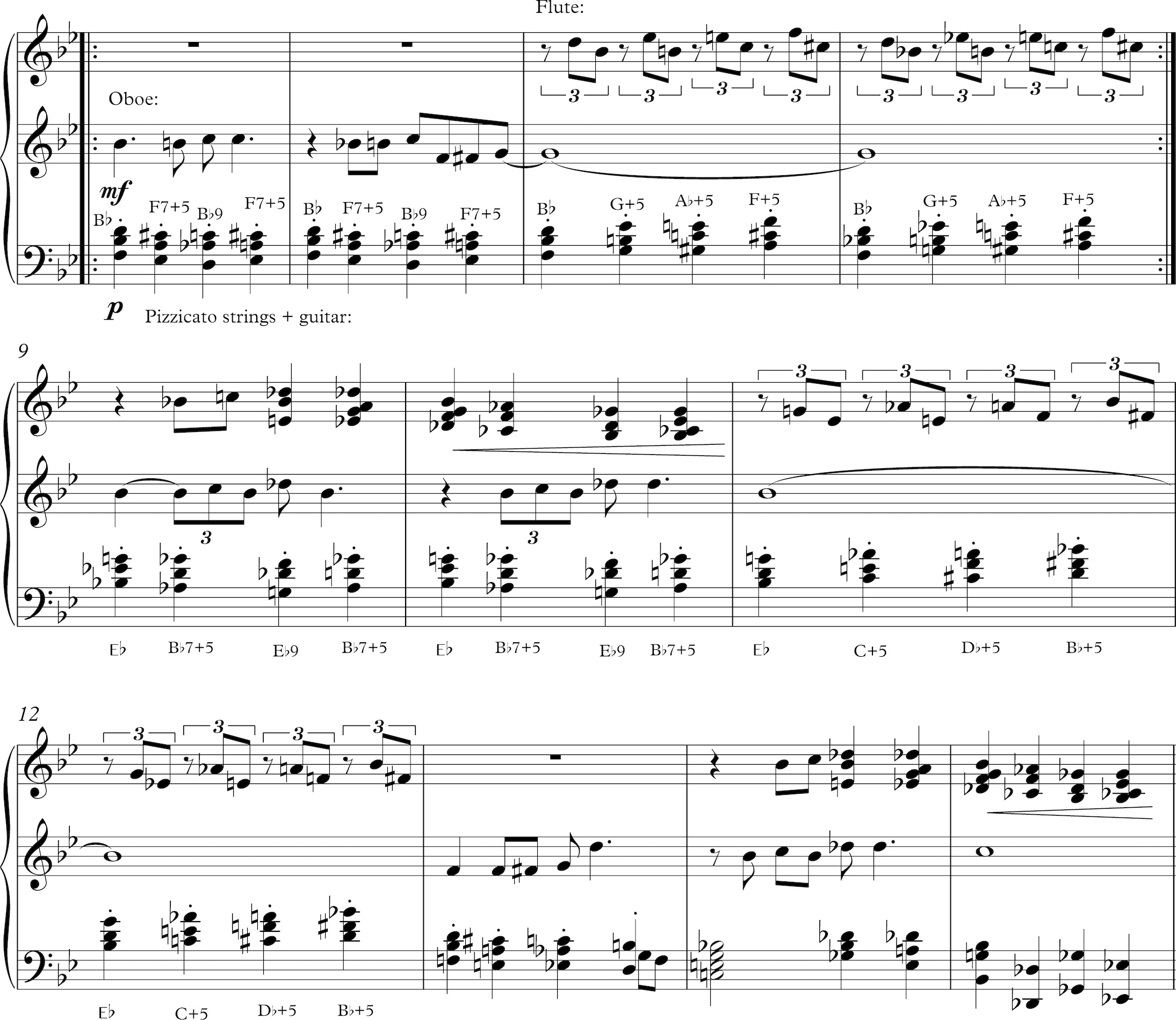

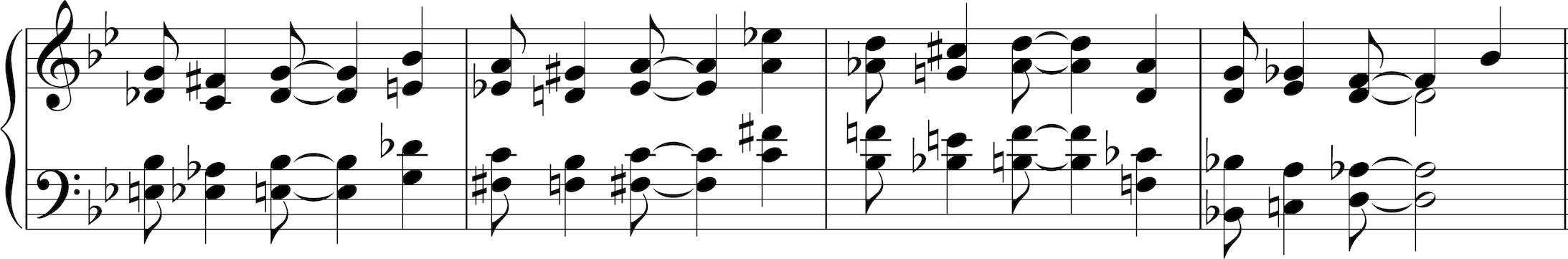

There are two themes, between which the transitions comprise mostly short, sequential motives over standard modulatory progressions. The first theme is stated in the oboe at the outset, and returns in the strings at m. 60, both times in Bb. I give here not only the melody, in the middle staff (and the repeat of the first four measures is written out, sans repeat signs), but also the pizzicato string chords that accompany the first statement, plus Johnson's chord symbols for the guitar part, which is not specifically notated (except for occasional melodic notes). One can see, then, along with the major and minor triads which tend to anchor the downbeats, Johnson's use of whole-tone type chords, either augmented triads or tritone-plus-major third. The chord symbols suggest more notes in the guitar than are present in the strings - for instance, F7+5 for Eb-A-C#, and Bb9 for D-Ab-C. On the top staff are given the parallel major thirds in the flute which fill in each cadence.

The appearance of the blues third Db in m. 10 creates an expectation, I think, that the melody will be a twelve-bar blues, but Johnson adds a fourth phrase that repeats the blues third and ends a little more ambiguously. The following transition is eight bars long, but Johnson elides the last measure of the sixteen-bar theme with the first measure of the transition for an odd-number count: a rather Mozartean touch.

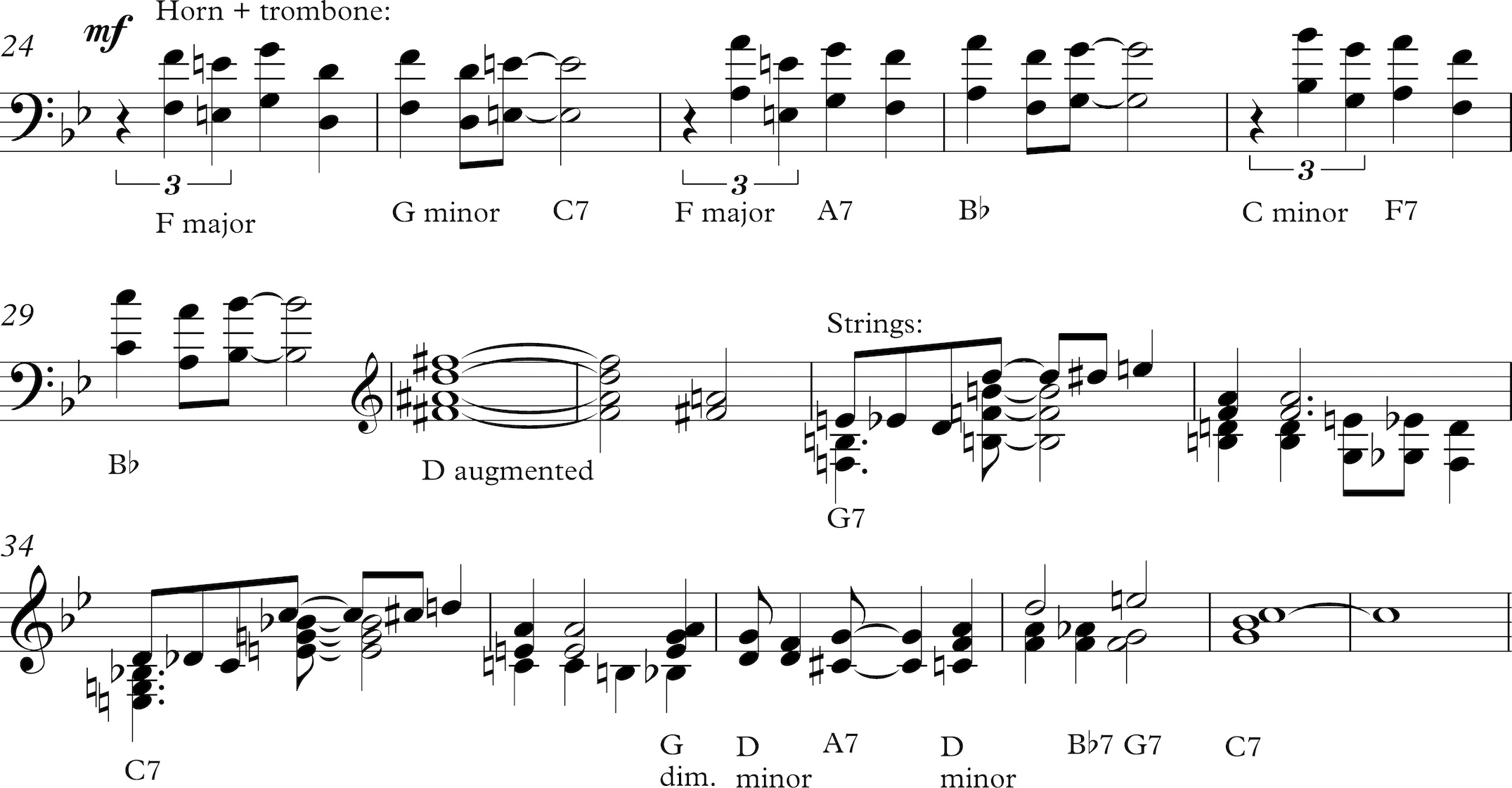

The second theme is labeled in the score "Harlem Love Song." It is an expansive thirty-two bars in length, alternating between winds and strings every eight bars. The style is grand Swing Era ballroom at its most cinematic, pausing on climaxes at sharped-fifth dominants and full of lush dominant major ninths. I provide here the guitar symbols notated by Johnson, but they don't account for the lushness of certain chords.

A perfunctory four-measure modulation returns us to the first theme, which, now in the strings, is a little more emphatically accompanied by much the same elements. The following transition starts out similar in rhythm to the analogous transition in the exposition, but two measures of chords stretch this passage out to nine measures (another odd-numbered macro-rhythm, and I can't imagine Johnson wasn't conscious of his balanced asymmetries). The last four measures of the transition seem poised to introduce a new tune, but instead merely return to the Harlem Love Song, now in the Bb tonic and more lushly orchestrated.

A four-measure coda threatens to end quietly at first, but ascends to a lush, Swing Era cadence with a sharped-fifth dominant and a trill figure dropping to the added sixth. One can imagine so many 1940s movies coming to a dramatic close with this phrase.

Third movement: The Night Club

First section -- mm. 1-84

Introduction -- mm. 1-12

First theme in Bb, strings -- mm. 13-28

First theme varied in Eb, trpt -- mm. 29-44

---- Transition -- mm. 45-60

First theme in Eb -- mm. 61-76

----Transition -- mm. 77-84Trio -- mm. 85-148

Second theme in Ab -- mm. 85-100

Second theme in Ab -- mm. 101-116

Second theme in Ab -- mm. 117-132

Glissandos in C -- mm. 133-140

Glissandos in C -- mm. 141-148Third section - mm. 149-186

First theme in C -- mm. 149-164

Second theme in C -- mm. 165-178

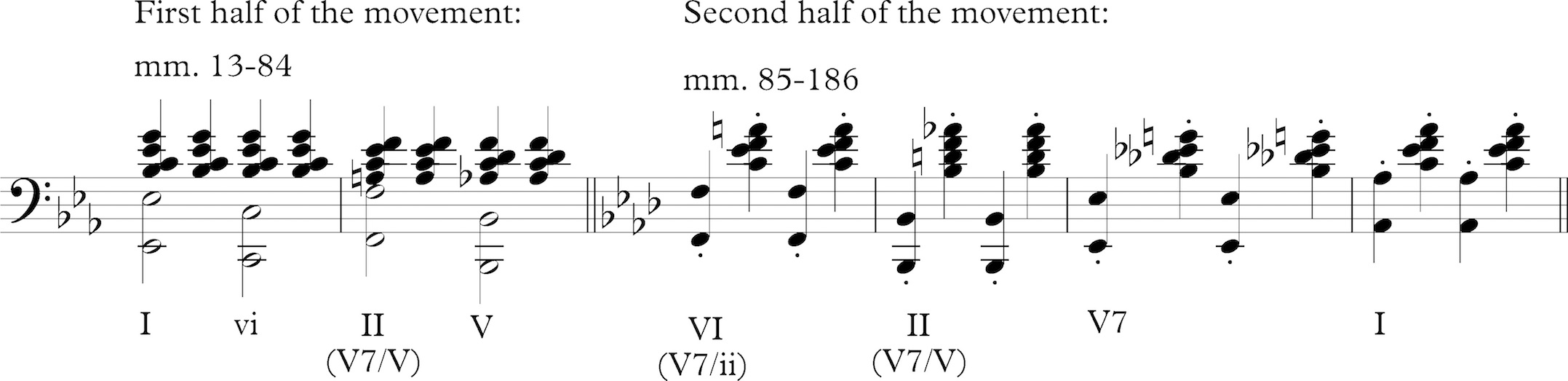

Coda -- mm. 179-186Johnson's third movement, "The Night Club," is a Harlem dance as scherzo. Look at all the section measure numbers up to 164, and you can see they're all divisible by four: this is a scherzo you can dance to. Johnson labels the second section "Trio," but what follows it, contrary to classical practice, is not a repeat of the first section. The first section moves from Bb quickly to Eb, and the Trio is in Ab, but the remainder of the piece is in C. The entire piece, though, is imbued with what jazzers call "Rhythm changes" (after Gershwin's song "I've Got Rhythm") - the chords VI-II-V-I. In fact, the deployment of this progression subtly differentiates the first and second halves. Until m. 84, every new theme starts on a I chord followed by vi-II-V in half-notes. From the start of the trio on, each new theme starts on a VI chord (V7/ii in classical terms), and moves through II, V, and I on whole notes, and this continues to be so in the final section in C major. Beginning each new phrase on V7/ii in the second half adds a new urgency to the music (you never know whether it's the beginning of a new modulation), and seems to up the craziness level of the dance a little. Johnson clearly knew how to exploit such subtleties.

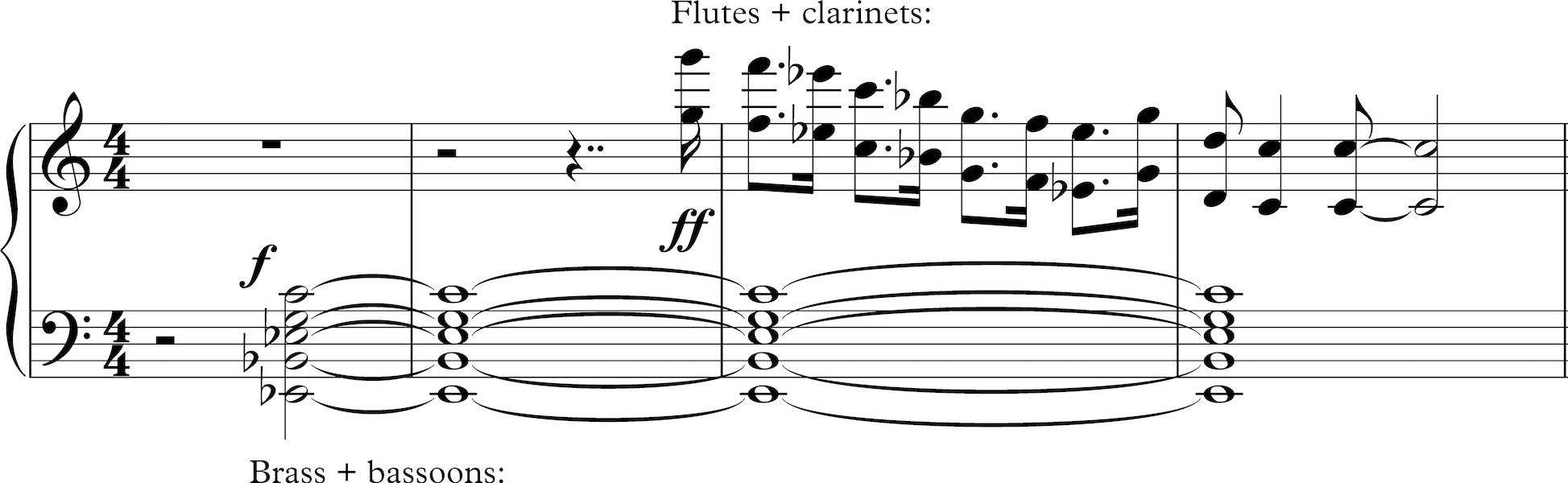

The movement starts with a hesitant, atmosphere-setting twelve-bar introduction, moving from Eb major with an added sixth to a Db dominant major ninth and back.

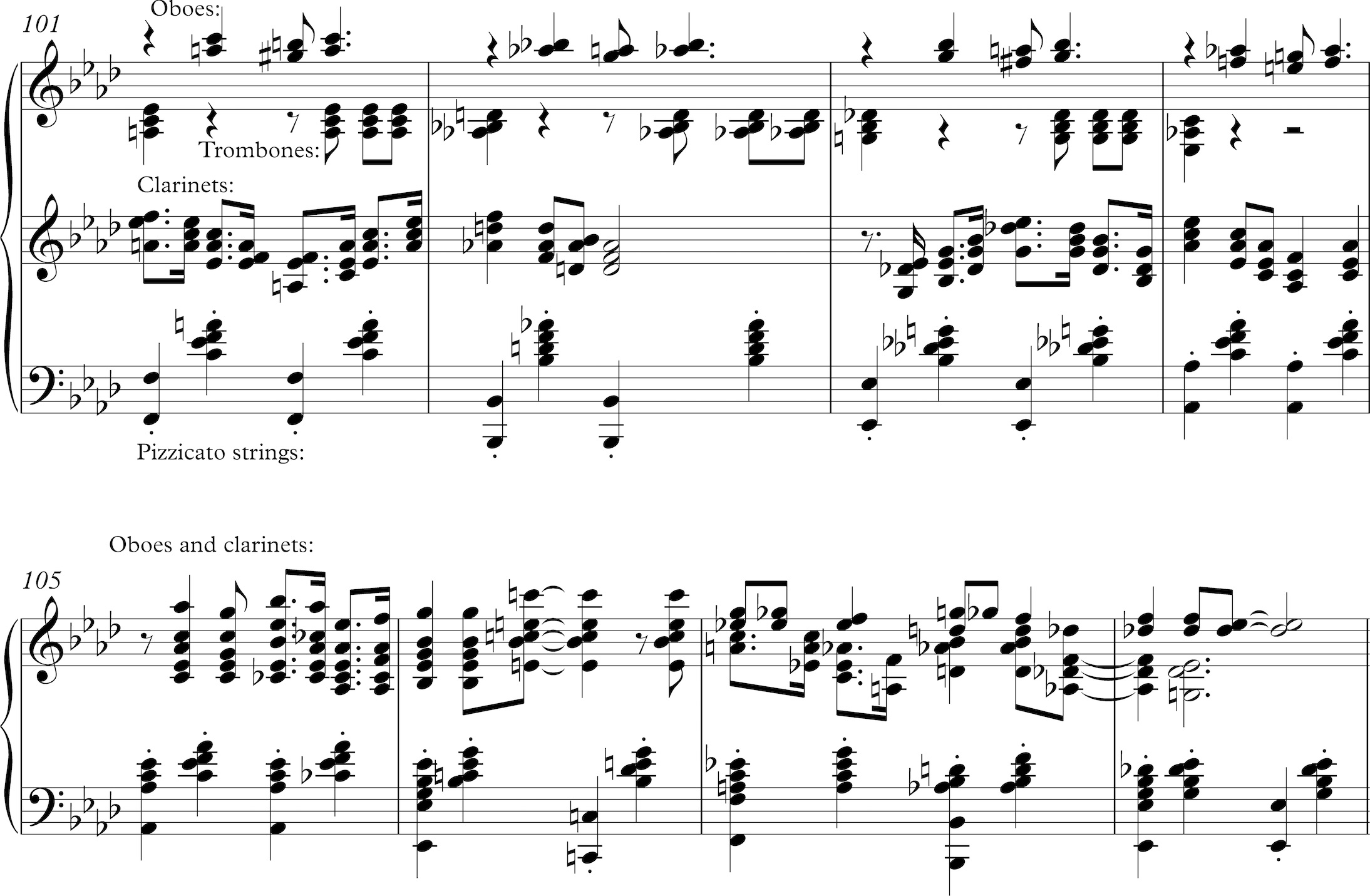

The first theme, in the violins, is sixteen bars, the last of which is diverted to a V7 of Bb, and the tune is restated in Bb in the trumpet, and it is clear that the eighth-notes must be swung. Comparison of the two consecutive versions how much freedom Johnson treats his melody with - as, in jazz, why would the trumpet play it the same way the strings do?

In fact, the trumpets replace the third phrase with a comedic reference to the I-VI-II-V that runs through the harmony.

The sixteen-bar transition that begins at m. 45 begins each half with a faux-dramatic passage of diminished seventh chords and dominants before relaxing each time into the dotted note texture prevalent earlier.

This leads to another statement of the first theme similar to the first, but in the upper winds. The bridge to the trio is an eight-measure pedal on Eb using jazzy syncopated chords to prepare for the Ab-major of the trio.

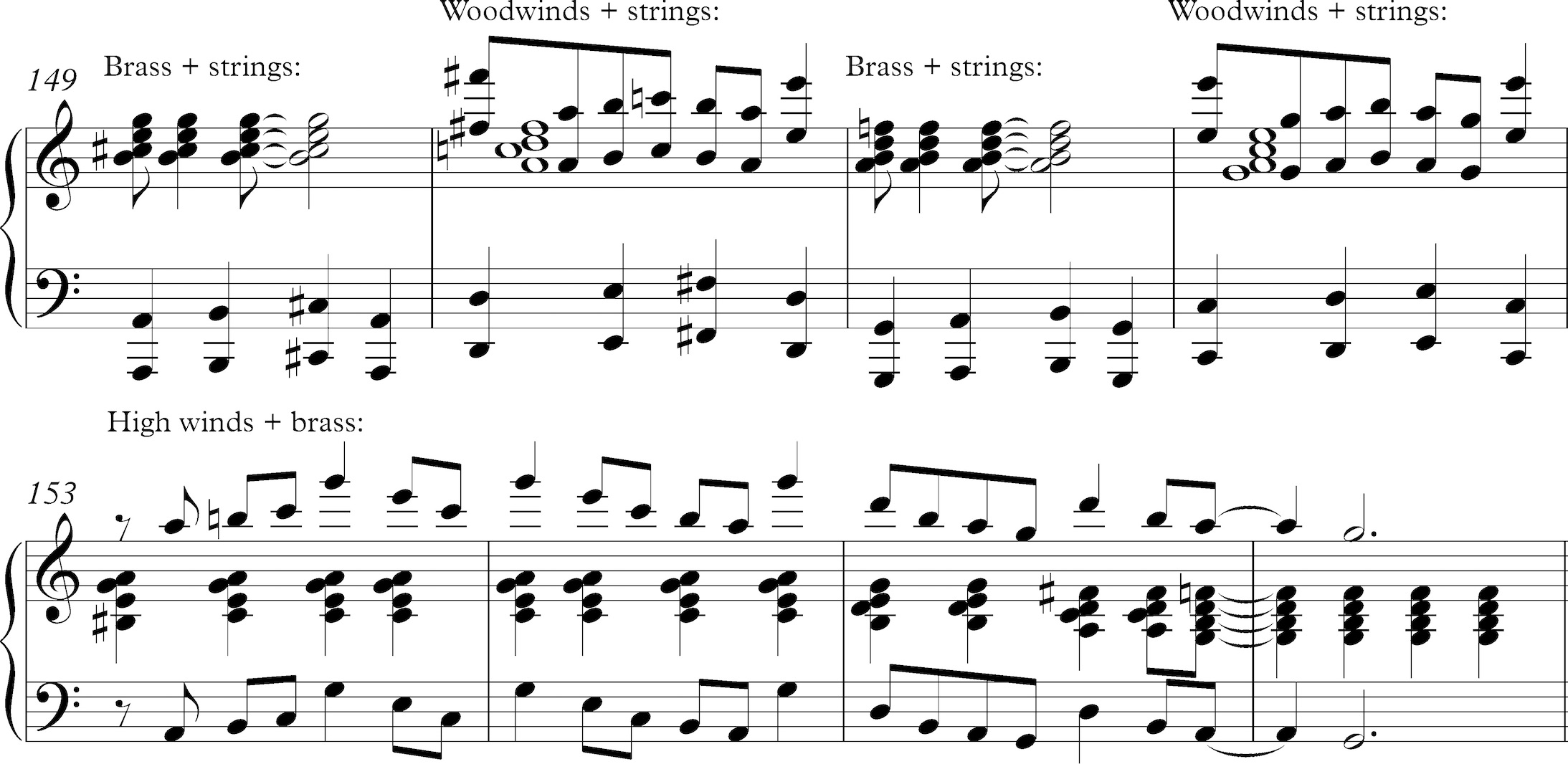

In mm. 85-132 the trio theme is repeated three times in varying orchestrations. Unlike the first theme, it begins more anxiously on the IV chord (V7/ii, actually) rather than on the tonic. This example from the second statement shows how thick Johnson's orchestration becomes, with the theme here once again in the trio of clarinets. Even more striking are the stride piano patterns in the strings, showing that at this point Johnson was simply orchestrating the piano style he spent his life playing.

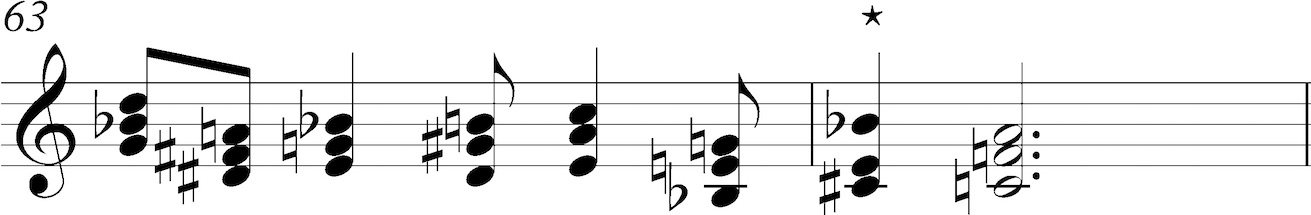

The third appearance of the trio theme turns to V7 of C just at the end, and over a VI-II-V-I in the low strings comes the most bracing section of the work: a back and forth of glissandos between the winds and strings, sometimes in both directions at once. No transcription could give the passage its due as well as the manuscript can.

The glissando section leads into a pair of sixteen-bar melodies on the by-now-familiar harmonic pattern, the first riotously orchestrated in a call-and-answer pattern.

The second is similar, but in tutti chords, and interrupted at the end, in time-honored Swing Era fashion, by a couple of piccolo cadenzas, before a dramatic final cadence with an augmented dominant.

Fourth Movement: Baptist Mission

Theme -- mm. 1-15

Var. I Allegro moderato -- mm. 16-35

Var. II -- mm. 36-51

Var. III -- mm. 52-67

Var. IV -- mm. 68-83

Var. V -- mm. 84-99

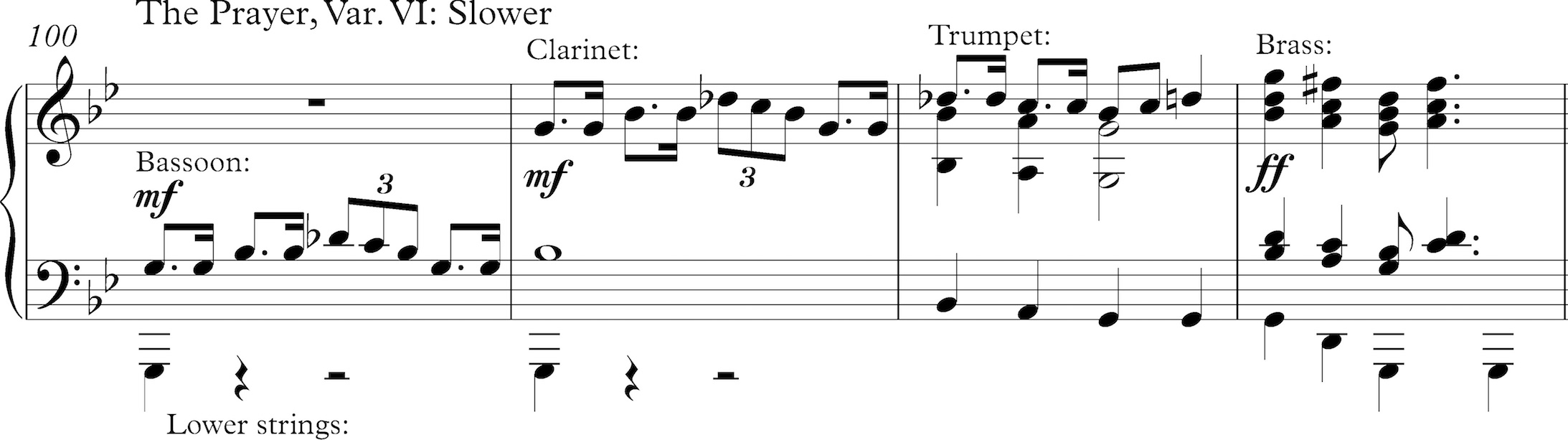

The Prayer - Var. VI -- mm. 100-127

Var. VII -- mm. 128-143

Finale -- mm. 144-157

Allegro -- mm. 158-177The fourth movement, Baptist Mission, is a theme and variations on a characteristic blues hymn. From the facts that it remains in G minor until almost the end, the theme is actually little varied, and that differences among the early variations are mostly decorative, one could conclude that it is a superficial example of the genre, but this is far from the case. As in a fervent revival meeting, the relative constraint of the first five variations allows a tremendous emotional momentum to build gradually, and after a momentary pause for prayer in Variation VI, the breaking loose in the denouement is all the more exciting in contrast to the first half's relative restraint. This is not a conventional theme and variations, but one that uses the repetitive variation form to build an effective dramatic trajectory.

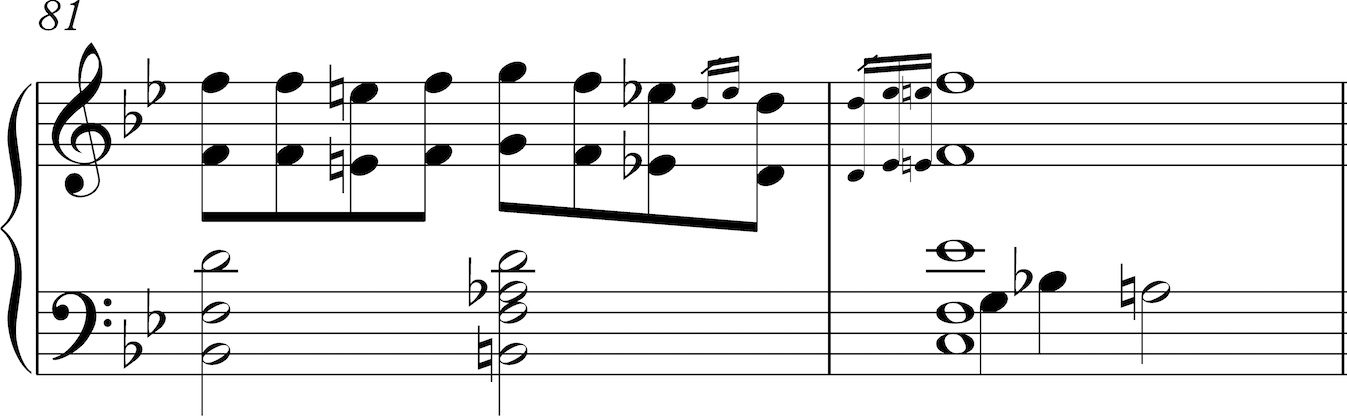

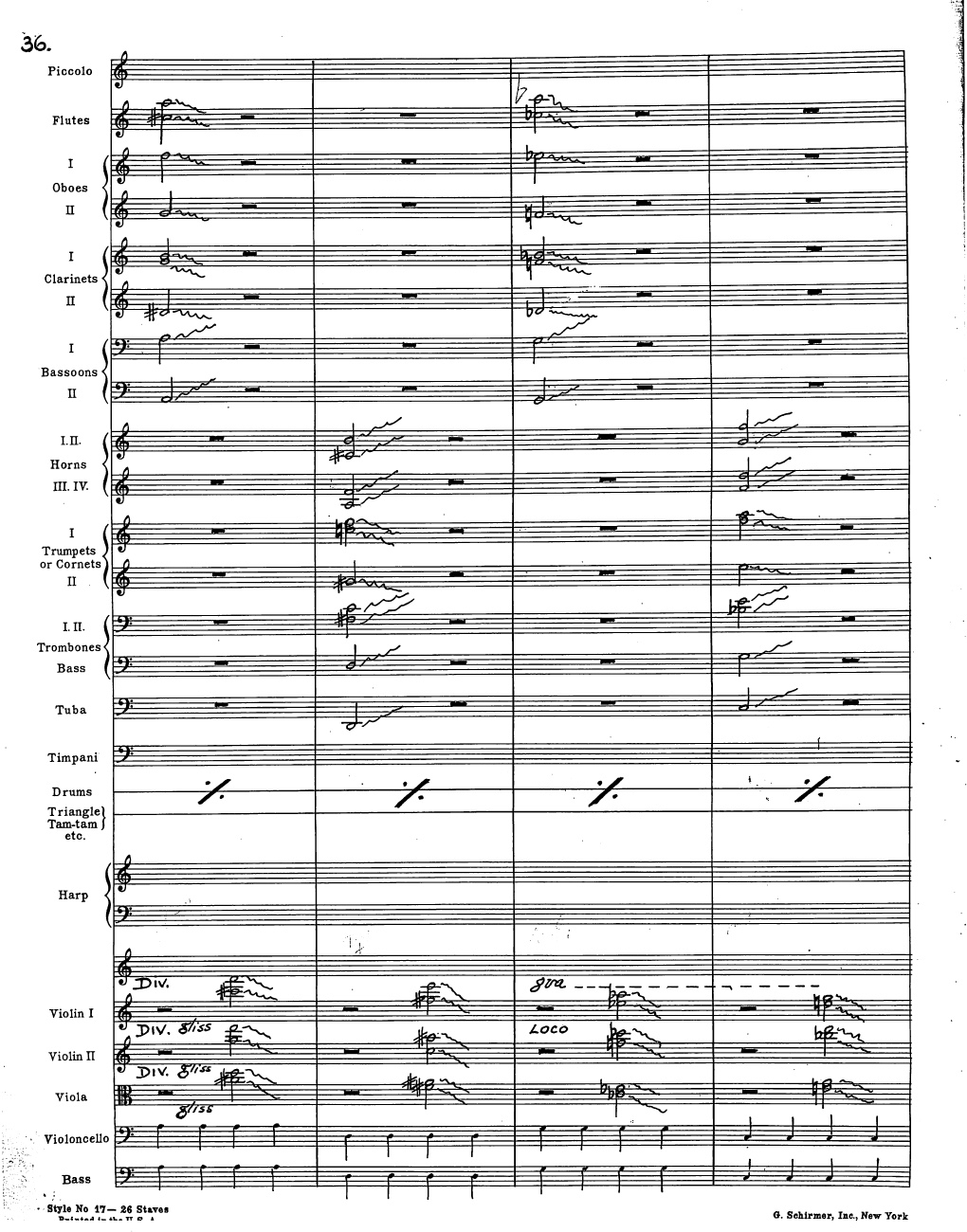

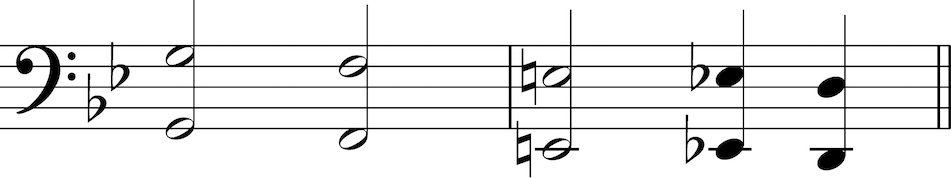

The theme is introduced at a languid largo tempo, with some of the lushest chromatic harmonization of the entire work.

From here on the tempo quickens considerably for most of the rest of the movement, introducing a bass ostinato that will run through the first five variations.

Variation I (mm. 16-35) simply states the hymn in a solo horn with a simplified string accompaniment.

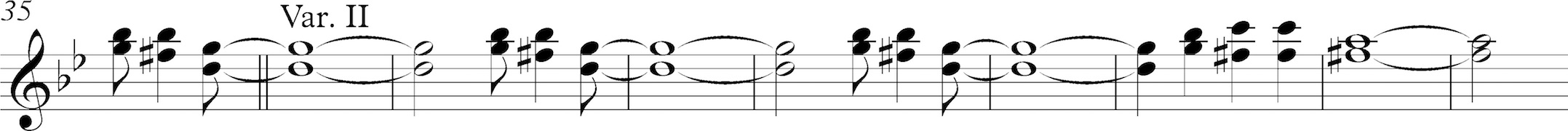

Variation II (mm. 36-51) puts the theme back in the strings, enlivened by periodic figures in the oboes.

Variation III (mm. 52-67) has the theme in the trumpet, while a clarinet plays a countermelody with a jazzy flat fifth (Db). The ostinato is taken over, with similarly bluesy harmonies, by the entire string section.

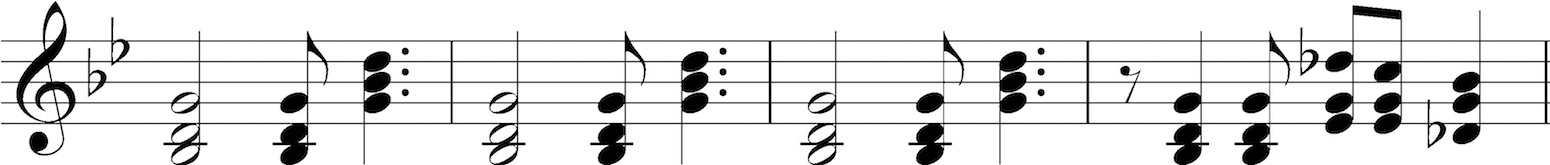

Variation IV (mm. 68-83) returns the theme to the strings, a bassoon, and trombone, with rippling arpeggios in chords in the flutes and clarinets.

Variation V (mm. 84-99), upping the energy level, has the theme in the oboes, accompanied by the strings and lower brass in jazz chords. The three trumpets punctuate it with syncopated figures.

Variation IV (mm. 100-127) is labeled "The Prayer," and takes the tempo down considerably. A dotted bluesy figure moves from the bassoon to the clarinet to the trumpet, as though different voices in the congregation are calling out.

The theme and ostinato start up again in m. 113, played by the winds and brasses.

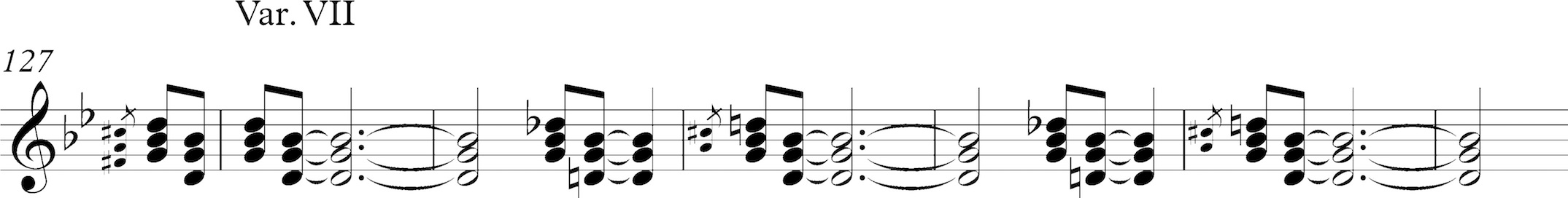

Variation VII (mm. 128-143) picks up the tempo to a quick two-step, and a note in the score indicates this brief variation is to be repeated, as though this were an afterthought. The trombone plays the theme as the strings sweep downward over and over through the ostinato. The focus, though, is a bluesy figure in the trumpets.

At m. 144 the Finale begins. A quick introduction goes through V/ii and V/VII chords to Bb, the second time turning to a German sixth and landing on a dominant. The entire movement has been in G minor, but at m. 158 the theme starts up and modulates, going into a Bb dominant and stating part of the theme in Eb minor. It makes its way to Bb minor, and them moves chromatically to a D dominant at m. 170. The final seven measures precipitously reinstate G minor over a chromatic bass line, and rise to a triumphant Picardy third.

Copyright 2019 Kyle Gann

Return to American Symphonies

Return to the home page