Roy Harris: Symphony No. 3 (1938)

Analysis by Kyle Gann

All score reductions by the author

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 3.0 License.The Symphony No. 3 of Roy Harris (1898-1979) continues to be a semi-famous piece despite the steep decline of its author's reputation - a decline for which the inferior quality of much of his late music was largely responsible. Still, it is not his only symphony worth rehearing. The naivete of his Symphony No. 4, "Folk Song," can strike modern listeners as a little cheesy today, but the Fifth, Sixth, Seventh, and Eighth Symphonies can inspire deep affection, and even the Symphony 1933 and Second Symphony are charming in their eccentric originality. (I have never found recordings of the Tenth or Twelfth.) I do think that Harris was more comfortable in one-movement symphonic form than in multiple movements; the Third and Seventh are his most convincing symphonies, and though I love the Sixth, it comes across as a series of independent pieces that could be played in any order. In his Third, though, Harris invented a compelling paradigm for a one-movement symphony divided into parts highly unified by theme, motive, and tonal conception, as well as flawless in its epic sweep. With its exuberance and inventiveness nevertheless leading to a starkly tragic denouement, I think of it as music's analogue to John Steinbeck's dark picture of America in The Grapes of Wrath.

The symphony has a textual problem, which is that for the initial recording (conducted by Leonard Bernstein, and still the best in my opinion) two cuts were made, from mm. 273 to 300 and from 307 to 315, shortening the Pastoral section by some 37 measures; these passages are omitted from Bernstein's recording, though included on some subsequent recordings. I have read different accounts of the reason for the cuts, some sources claiming that they were only reluctantly made to fit the symphony on one side of a vinyl record, others inferring that they were intentional and permanent, though they remain in the published G. Schirmer score. I will treat them here as part of the symphony, with the caveat that this analysis will depart from the well-known slightly abridged version.

Form:

1. Tragic -- mm. 1-151

Chant -- mm. 1-56

Main theme in strings -- mm. 57-96

Main theme in winds -- mm. 97-130

Transition -- mm. 131-151

2. Lyric -- mm. 152-2083. Pastoral -- mm. 209-415

Polychords -- mm. 209-386

Two-measure chords -- mm. 209-268

One-measure chords -- mm. 269-326

Half-note chords -- mm. 327-386

Buildup to fugue -- mm. 386-415

4. Fugue - dramatic -- mm. 416-5545. Dramatic- tragic -- mm. 555-703

Main theme canon -- mm. 555-633

D pedal point -- mm. 634-703The introduction to Harris's Third, mm. 1-56, seems intended to replicate in miniature the history of European music itself:

mm. 1-24: monophony

mm. 24-41: melody doubled in fourths and fifths (organum)

mm. 42-56: polyphonyThe cellos open with a single line in G major in which, in an original touch, certain notes are taken over in crescendoing octaves by the violas.

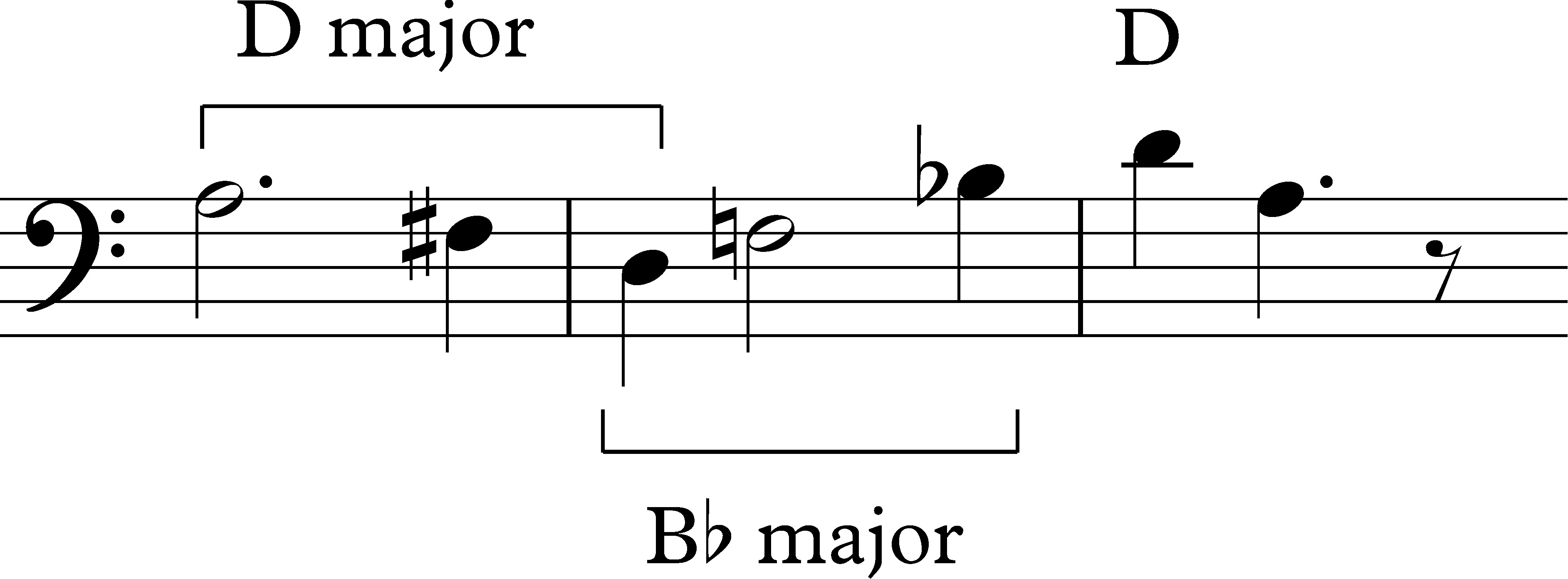

Oddly, this long line foregrounds no specific motives that have significance for the rest of the work. What the melody does prefigure is Harris's tendency to use tones to pivot from one key to another. The line moves by steps and consonant intervals such as thirds and sixths. Major and minor become interchangeable. For instance, in mm. 16-18, the line proceeds through a D-major triad to a Bb-major and back: these exact pitches will later become a nucleus of the Lyric section theme.

Likewise, in m. 22 an F# in D major becomes a pivot tone into B major. We will find this tendency pervasive and generative of much material. At m. 28, after the melody has acquired Harris's trademark fourths and fifths (and note that these fourths and fifths are not always parallel - Harris particularly enjoys the harmonic shift of moving from a fourth to a fifth within a melodic octave), the music seemingly in E major shifts to minor, and then a G-major passage pivots through B and F# back to E (or A) major, then the C# and G#, possibly taken as Db and Ab, pivot into Bb, which fluctuates between major and minor.

The tonality wanders in a generally diatonic kind of way, never dissonant or atonal, but often switching keys smoothly and sporadically. (It is interesting to compare this approach to tonality to that in the Third Symphony of Harris's friend Aaron Copland. The latter will occasionally change key gradually by adding in one new accidental at a time, but most of his key changes are abrupt and clear, and very few passages exhibit the kind of ambiguity Harris so delights in. We can also note that Copland changes key signatures frequently; Harris eschews them.)

At m. 41 we reach the first unambiguous and even triumphant triad, of B major. From mm. 42 to 56, the music, branching out into four-part polyphony, is more or less in B, but it is a variably modal B, mixing mixolydian, dorian, and natural minor. More remarkable is how the entire passage remains mostly in fourths and fifths, even stacked fifths at a few points. Leaps of a sixth become common, and will figure motivically later in the work.

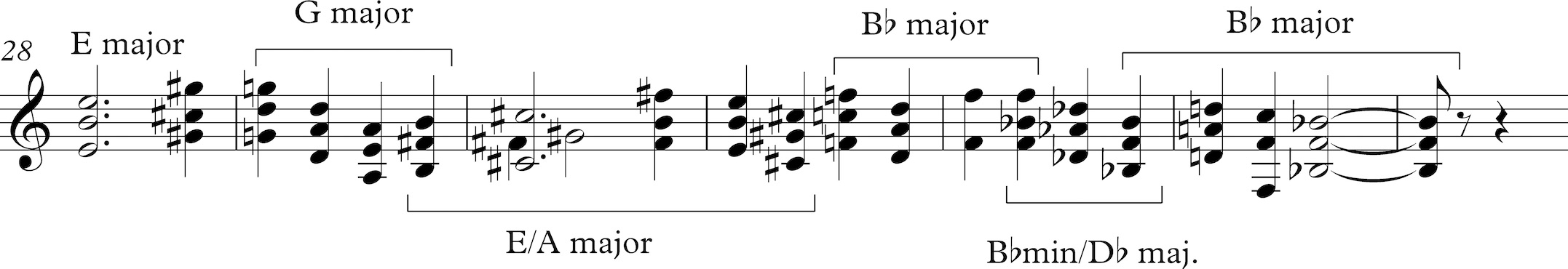

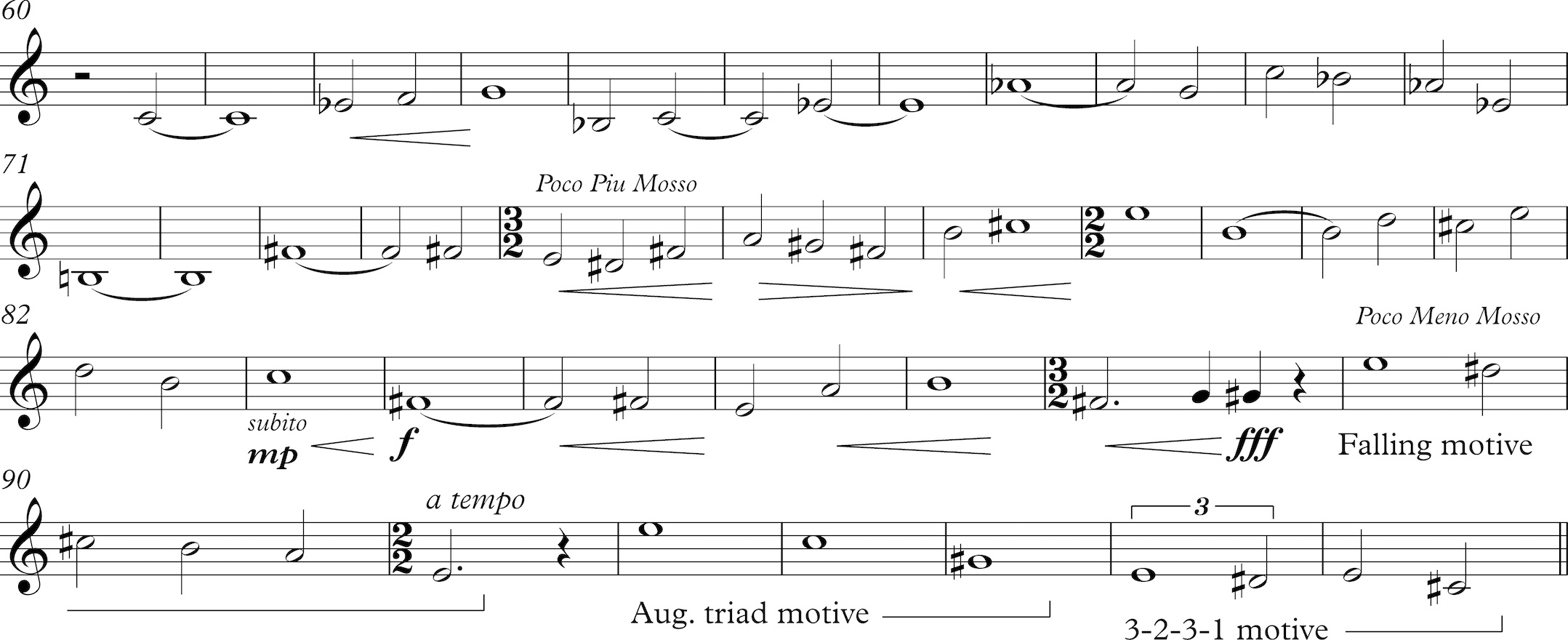

At m. 57 the music pauses on a dominant of F# and C#, the F# moves to Ab, and the C# then to Eb. At m. 60 the long (37 mm.), languorous main theme begins, and we give it here in its entirety since it will come back three more times. The Third Symphony began life as a violin concerto that Harris later abandoned, and this melody was the beginning of the solo violin part. It ends with three motives that will take on significance by themselves, which I will call the falling motive, the augmented triad motive, and the 3-2-3-1 motive (this last named for its apparent scale steps).

This wandering melody, at its slow tempo, is not easy to recall, and seems almost more a series of motives than a unified tune. Its immediate return in the winds a major sixth higher at m. 97, past the first few notes, is not readily recognized as such, and though it will become the basis of the Dramatic-Tragic section at mm. 537-633, in canon with itself, it is not obviously recognizable there either. Unlike Copland's themes, whose mottos are always easy to place, this one lends unity to the entire work, but in a subtle, underlying way. In fact, in retrospect we can see why Harris didn't make his long, opening melody more of a theme, in the sense of having recognizable elements that would come back: he needed it to be even lower-profile than this still not-very-high-profile theme meant to occupy a larger place in the piece. A more memorable tune at the beginning would have ruined the effect.

Notice that, taken by itself, the melody seems to be in Eb major for eleven measures, pivoting on a minor third scale degree at m. 71 to go into B mixolydian/minor, and that it seems to go into E major/minor at m. 83. This, however, is not at all how Harris harmonizes it. He places it in counterpoint with his usual fourths and fifths in the bass, and in the example I show over each melody note what scale step it represents in terms of the chord underneath. Root movement of the fourths and fifths is mostly step-wise, and more often major seconds than minor. The roots of the first seven chords are in a Db-major scale, creating a kind of bitonality, and other such scales are momentarily evident afterward; for each melody note I have marked what scale degree it represents relative to the chord beneath it, and it is not always a chord tone.

Harris once wrote, "Harmony should represent what is in the melody, without being enslaved by the tonality in which the melody lies. At the same time harmony should center around a tonality sufficiently to indicate that tonality, because tonality is absolutely essential to form, and to harmonic contrast." This passage illustrates that principle fairly well - the Db major beneath the G in m. 63 is easily heard as a kind of mixolydian cadence resolving back to the succeeding Eb major, and by m. 69 the accompaniment tonality is moving along the area of C, D, and E. It is worth noting that no matter how triad-oriented Harris's harmony is, he manages an effective sense of harmonic motion without any of the usual syntactical methods of conventional tonality (for example, root movement by fifths and dominants).

At mm. 97-130 the theme's first 32 measures are restated, with minor deviations, in octave unisons in the massed woodwinds. The accompaniment here is lighter, mainly a countermelody in the violins that inflects the tonality with much major-minor nuance, plus some quasi-cadential notes in the lower strings, mostly pizzicato. Some of these (mm. 102-103, 108-109, 121-123) are sequences of rising perfect fifths, which will appear as a motive later in the Fugue section as well.

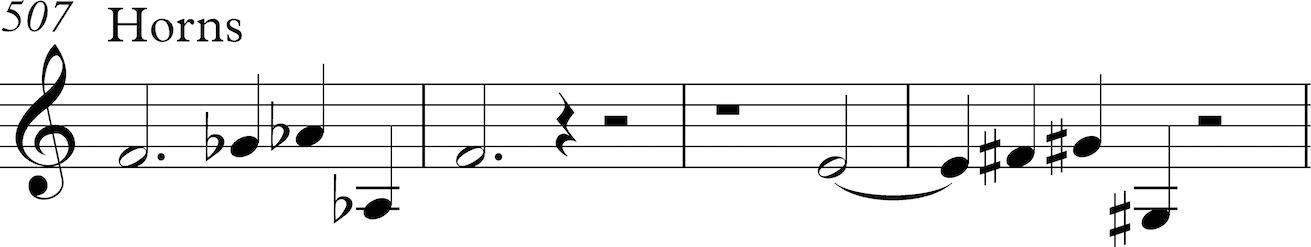

It has never been quite clear to me, and it is not marked in the score, exactly where the second, Lyric section is supposed to begin. (Other writers have remained mute on the subject.) That the transition occurs between mm. 131 and 152 can hardly be doubted. The violins rise to a monophonic climax with poignant octave leaps in mm. 131-135, leading to a tragic-sounding return of the 3-2-3-1 motive, which had been omitted from the preceding second statement of the main theme. Then over a hushed G minor triad (the key the symphony will end in), the flute plays the augmented triad motive, leading to another 3-2-3-1 motive a minor third higher. Harris continues to develop a theme from this freely, as the horns twice introduce a triadic motive that will be pervasive in the Lyric section.

The quarter-note momentum that starts up the Lyric section is at first accompanied by the low strings and winds playing the falling motive from the main theme, which had also been omitted from the main theme's second statement.

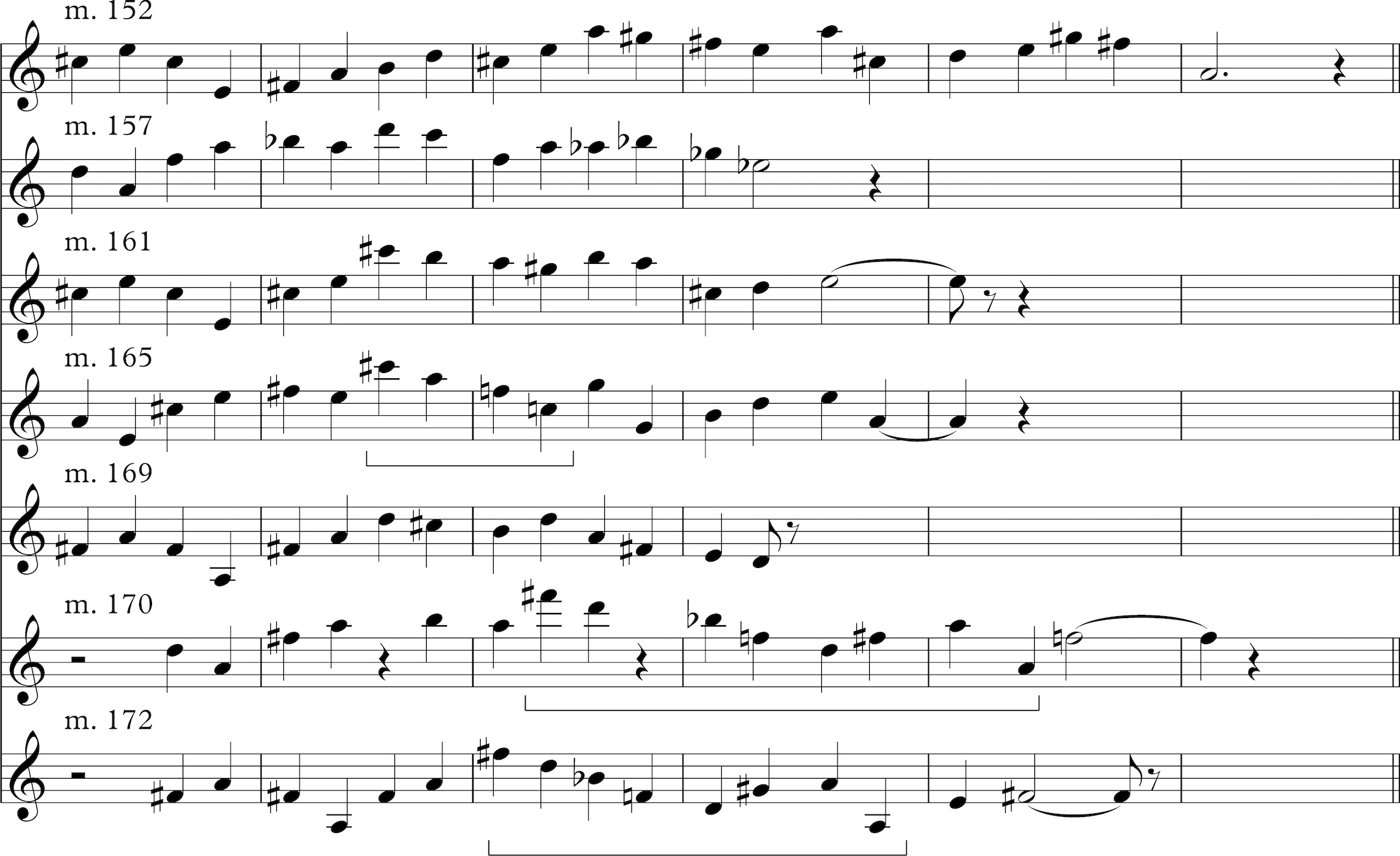

Commentators have referred to a "Lyric theme" on which this second section is based, but the theme exists only as a type, not in any single recurring form. The first seven occurrences are given in the next example. Each begins by outlining the notes of a triad emphasizing the major sixth between the third and the fifth, and some of the triad notes acquire neighbor notes. Whether starting on an A or D major triad, some of the versions turn toward the minor scale momentarily, and in particular the conjunction of D major and Bb major, which has already been presaged in the introduction, is increasingly evident. Brackets beneath some of the lines in the example note an evolving motive of two descending major thirds followed by a descending fourth that derives from this conjunction: F#-D-Bb-F. The final, extended form given here at m. 174 will come back as a fff gesture in the strings at m. 186.

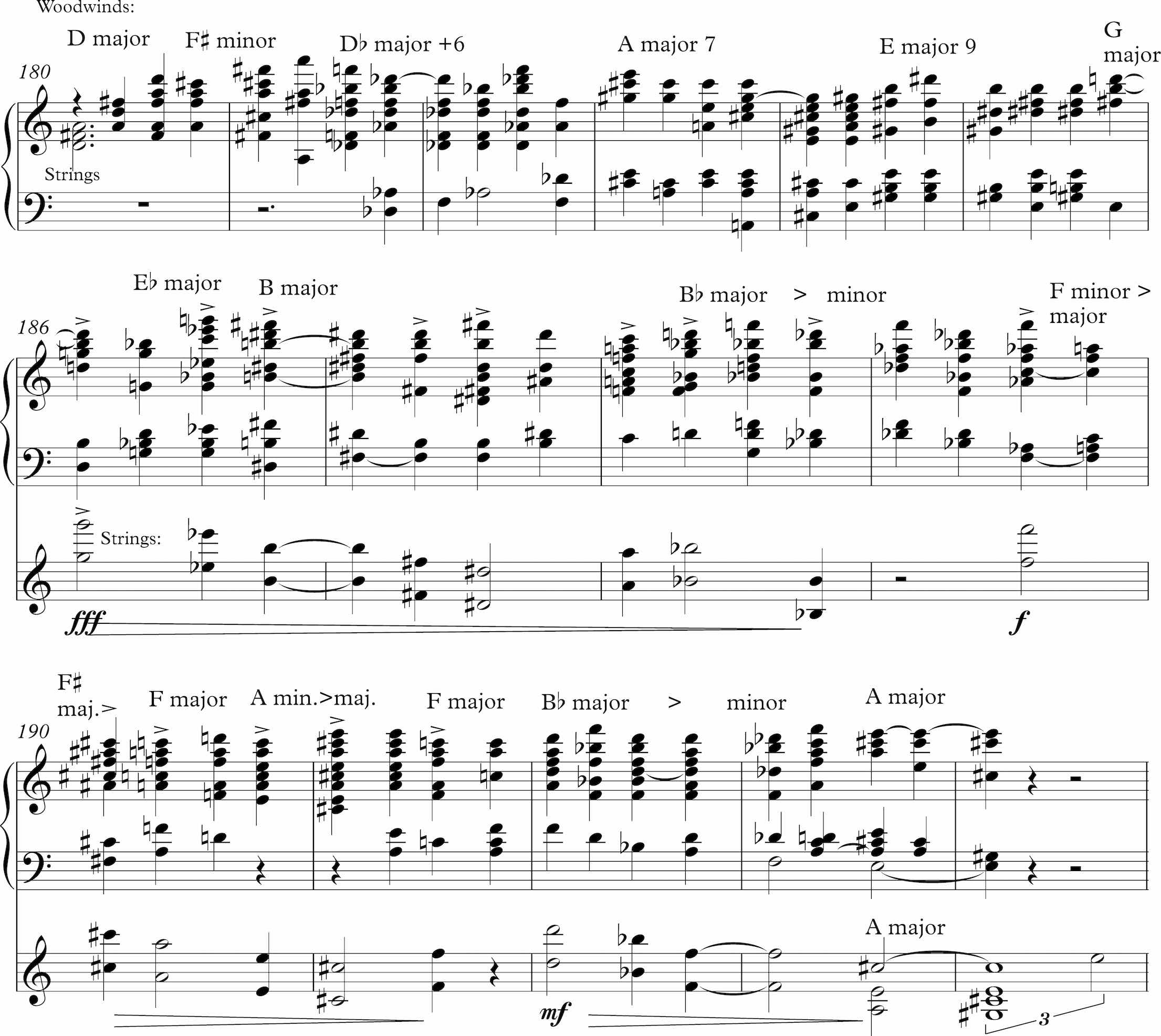

After bouncing several such themes back and forth among sections of the orchestra, in mm. 169-179 Harris combines four at once based on the D major triad, and by flickering between D major and Bb major the coincidence of lines sometimes creates almost unintended-seeming peripheral triads, such as the F# major at the beginning of mm. 173 and 177. This process is greatly intensified at mm. 180-193. A listener familiar with the score might hardly recognize the big block chords of the next example, but play them on the piano and the passage will spring to mind. All the woodwinds are given separate lines based on the lyric theme, but together the notes make triads covering several octaves, and the resulting lines modulate smoothly through a panoply of keys. The harmonic rhythm plays against the meter by sometimes changing keys every six or three beats. The lines with the strings come crashing in on unison octaves is a rhythmically altered version of the motive played by the violins at m. 174, bracketed in the preceding example: two descending major thirds, a descending fourth, and so on.

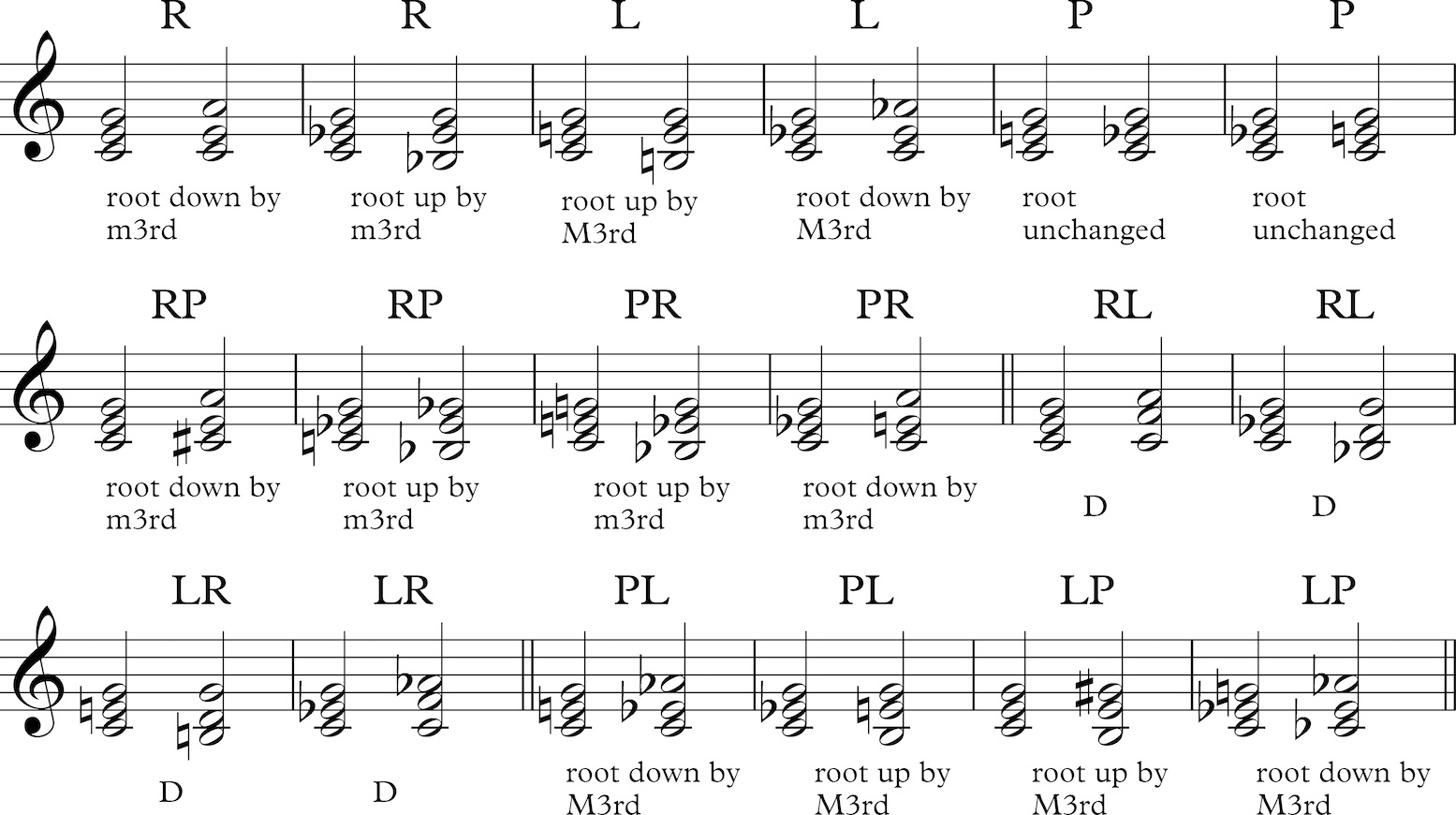

The D major/Bb major conjunction observed in the introduction is a paradigm for these modulations. The D is a pivot between the two triads, F# moving to F and A to Bb to go from D major to Bb major. This kind of voice-leading is now referred to as neo-Riemannian, after the branch of neo-Riemannian theory created in the late 1980s by David Lewin, Brian Hyer, Richard Cohn, Henry Klumpenhouwer, and others. I refer the reader to other articles on the theory for a fuller explanation, but in their notation a P (for parallel) transformation lowers the third of a triad to make it minor, or raises the third of a minor triad to make it major; the R transformation (for relative) raises the fifth of a major triad by a whole-step to create the relative minor triad, or lowers the root of a minor triad by a whole-step to give the relative major; the L transformation (for leading-tone) lowers the root of a major triad a half-step to create a minor triad, or raises the fifth of a minor triad a half-step to create a major triad; and a D indicates a simple moving of a chord to its dominant or subdominant.

The transformations can also be combined, so that an RP raises the fifth of a major triad a whole-step a major second and the root a minor second to change, say, C major to A major; and so on as in the diagram.

The transformations can also be triple or quadruple, but we only need single and double transformations in Harris's symphony, because one or two pitches usually remain as pivots to the new harmony. Thus the harmonies of mm. 180 to 193 in the example above can be plotted as a series of mostly neo-Riemannian transformations as follows, with the other harmonic changes always shifting the tonality by a half-step in its entirety. Of course Harris was not thinking of neo-Riemannian theory (which would not be invented until fifty years after he wrote the Third, after all), and had no thought of limiting himself to it, but he was clearly composing with the same principles in mind, moving from harmony to harmony via pivot tones.

Harris ends the Lyric section with a transitional passage, mm. 194-208, in which the violins spin out a slower theme based on the lyric theme motives, as the harmonies continue to move via pivot notes. The example below employs one S (slide) transformation, in which the third of a minor triad remains while the root and fifth slide down a half-step to create a major triad.

The passage ends on D major as preparation for the next large section to begin in A major.

The "Pastoral" section (mm. 209-415) is one of the most famous passages in American music: a continuum of floating, often polytonal, and ever changing chords above which woodwind melodies spin from key to key. The chords are played in continual overlapping arpeggios by the strings.

The harmonic rhythm accelerates in three approximately equal phases as follows:

mm. 209-268: chord change every two measures

mm. 269-326: chord change every measure

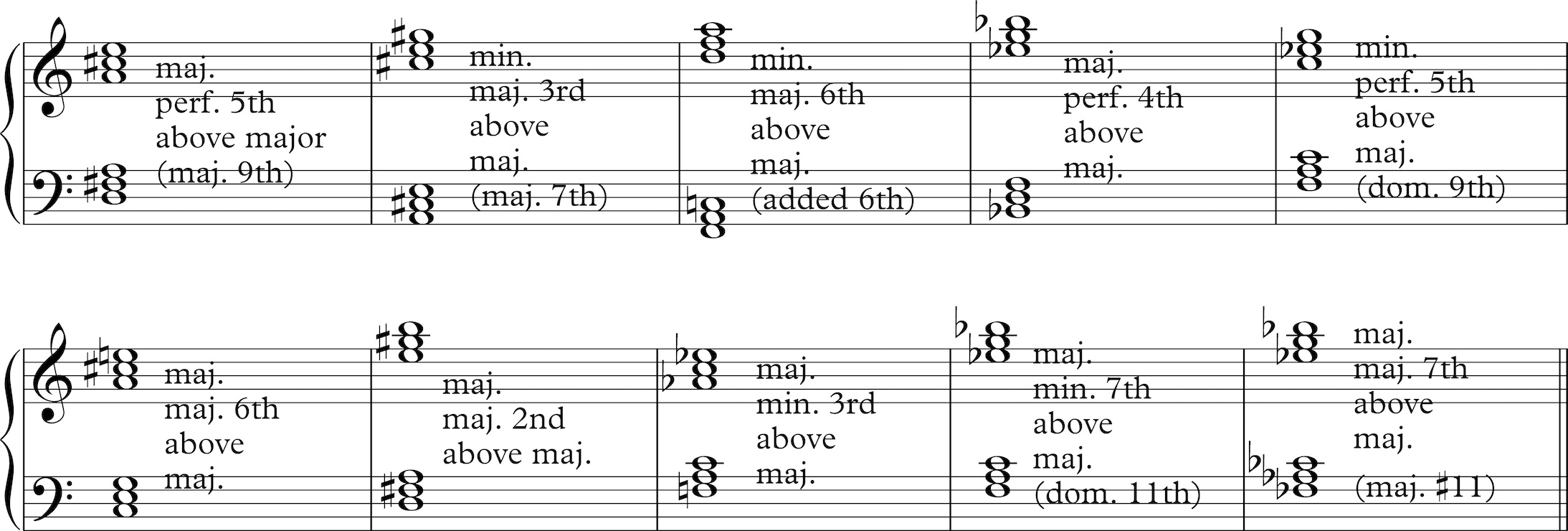

mm. 327-386: chord change every half-noteEvery harmony is a combination of two triads, the bottom one always being major. The root of an upper major triad can be a perfect 5th, perfect 4th, major 6th, major 2nd, minor 3rd, minor 7th, or major 7th above the root of the lower one, in that order of frequency. The root of an upper minor triad can be a major 3rd, major 6th, or perfect 5th above the root of the lower one. Thus of the twenty-two possible combinations of two triads (eleven major and eleven minor with respect to the base triad), Harris limits himself to ten, as follow in order of their frequency of use:

1. major triad a perfect fifth above: basically a major 9th chord, such as C-E-G-B-D

2. minor triad a major third above: really a major 7th chord, such as C-E-G-B

3. minor triad a major sixth above: really a triad with an added 6th, such as C-E-G-A

4. major triad a perfect fourth above: the same pitch content as chord #1, but reversed in register

5. minor triad a perfect fifth above: really a dominant 9th chord, such as C-E-G-Bb-D

6. major triad a major sixth above: bitonality such as C-E-G and A-C#-G

7. major triad a major second above: bitonality such as C-E-G and D-F#-A

8. major triad a minor third above: bitonality such as C-E-G and Eb-G-Bb

9. major triad a minor seventh above: a dominant 11th chord, such as C-E-G-Bb-D-F

10. major triad a major seventh above, such as C-E-G-B-D#-F#

(There are, for instance, no chord assemblages with triad roots a tritone apart, nor any with the upper triad a half-step above the lower, and so on.) About three fourths of the chords Harris uses are from categories 1, 2, and 3, which are non-bitonal seventh, ninth, and added-sixth chords, so this famous passage's reputation for bitonality (promoted by Harris himself) is a little overblown, though it is beautiful nonetheless. Chord 10 only occurs twice, at mm. 311 and 318, both times on Fb and Eb. More accurately, the passage revels in sonorities of major triads with added major sevenths, major ninths, and major sixths.

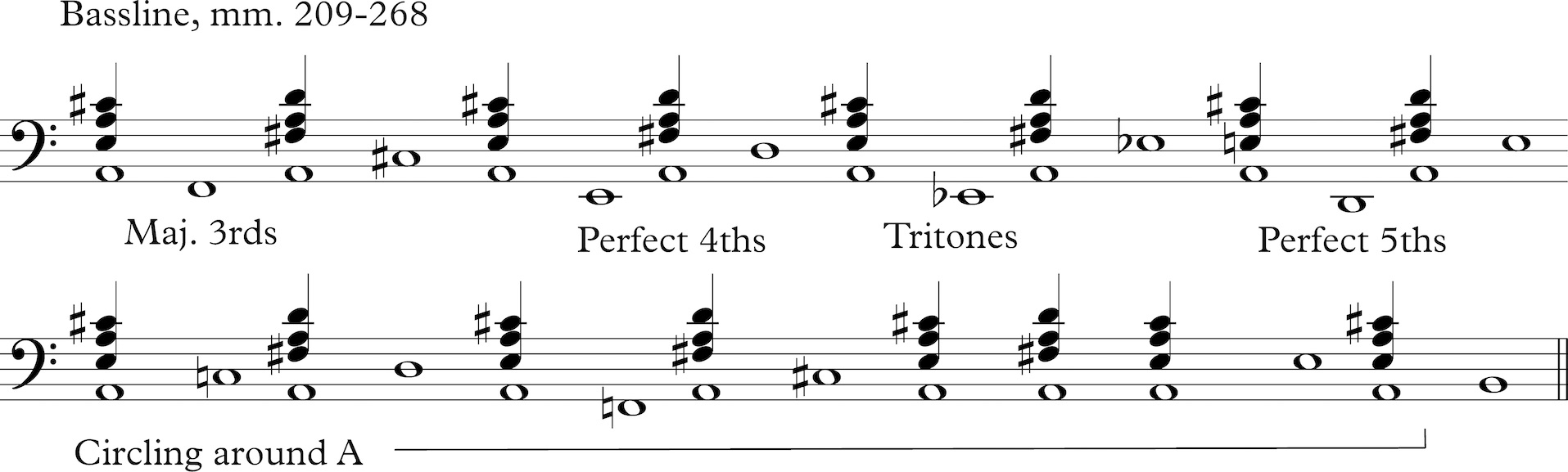

The succession of chords is not easily described, and Harris seems to choose individual chords intuitively. If we look at the bass lines, though, an underlying plan that he must have used as a guideline is clear. To begin with, the bass line for the first and longest section, mm. 209-268 (and every whole note here stands for two tied whole notes in the music) clearly revolves around A, first moving a major third in each direction, then a perfect fourth, a tritone, and a perfect fifth before becoming more irregular. And the A's in the bass are alternately harmonized by A major and D major in the lower triads.

The entire passage, then, has a general feel of A major that keeps dipping into Ab major, then other keys around A such as C major and F# major, the woodwind solos generally making the momentary tonality clear. The recurrent returns to A and D major render the passage calmly stable despite the exotic digressions; every chord on A continues to feel like a return. Note also the strong tendency toward contrary motion between the bass and the highest violin notes, which create a pleasant feel of the orchestra swelling and ebbing, like a breathing organism.

Note also that Harris's prolixity of triads allows for abundant neo-Riemannian chord progressions The second upper chord of D minor moves to an F# minor triad that would be described as a PL transformation; from F# minor to the following Bb minor is an LP transformation, moving through an RP transformation to the subsequent C# minor, and so on. That Harris could achieve such a phantasmagorical rainbow of harmonies while still keeping the music rooted in a lightly inflected A major is a masterpiece of technique. The passage is justly famous.

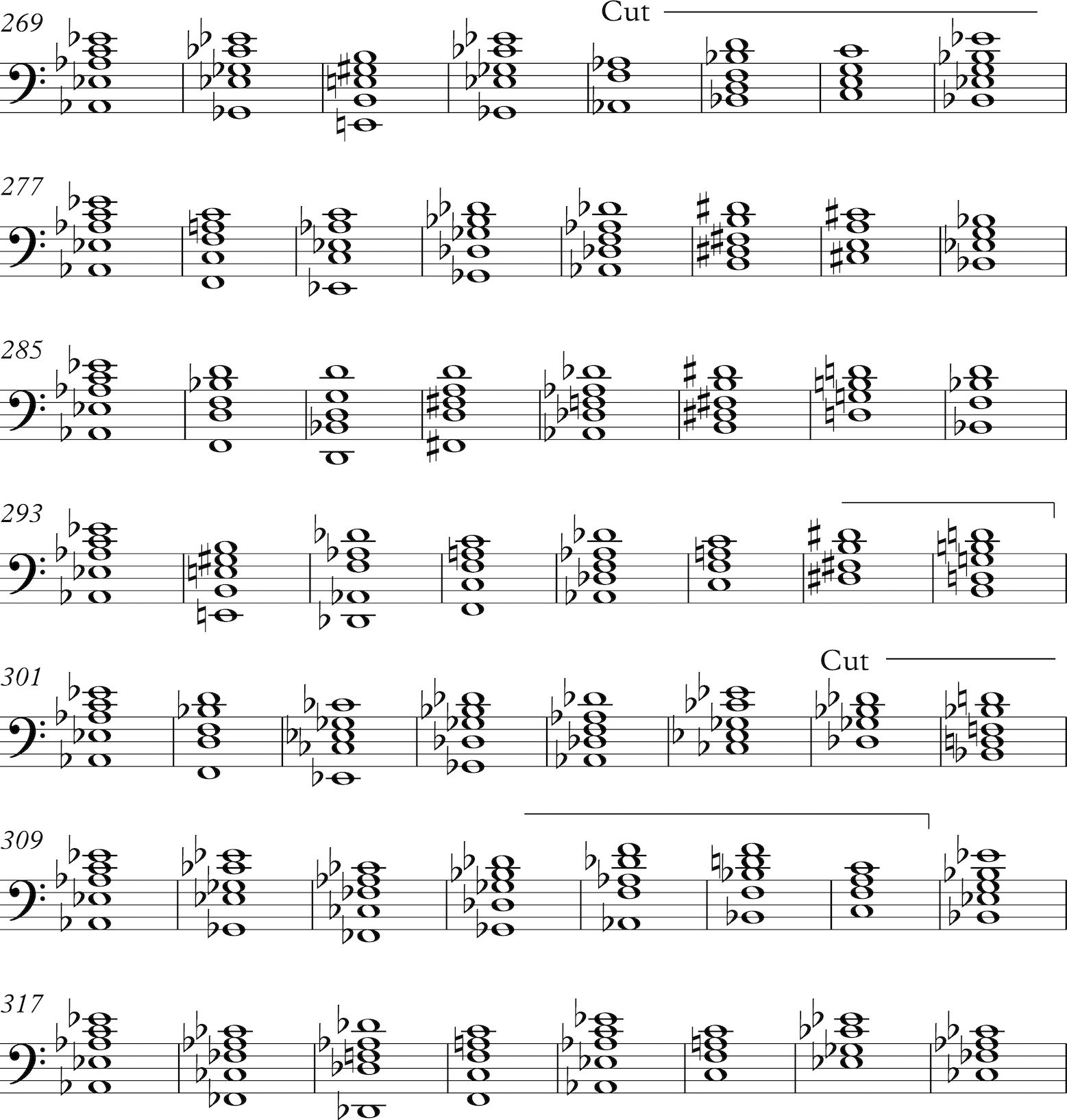

At m. 269 the mood shifts toward greater instability, and the harmonic rhythm doubles to one chord per measure. In this next section, mm. 269-326 (though the 37 measures cut for the Bernstein recording are all from this section), there is evidence that the harmonic progression is still at least partly determined by the bass line. The following chart shows the lower string chords for the entire section in eight-measure phrases. A glance down the column shows that each eight-measure phrase begins with an Ab-major triad (and the upper strings play a C minor triad at each of these points, for a composite Ab major seventh). The fifth chord in each line also has an Ab in the bass, though always harmonized with a Db major triad except for the final one at m. 321. In between the first bass line phrase descends a major third (in whole steps), then ascends a major third; in the second phrase the range is a perfect fourth in either direction, then a tritone in the third phrase, next a perfect fifth, then back to a perfect fourth, then a major third, then a perfect fifth again. Between the Ab's in each phrase the intervals between bass pitches change to accommodate the changed intervals covered by the roving bass line. This is an expanded pattern similar in concept to the bass line of mm. 209-268, anchoring the music around Ab and Db rather than A and D, and it is clear that Harris employed these patterns in his bass line to help determine the succession of chords. It is also clear that cutting out two passages detracts from the symmetry of this structure, though the bass line retains its conjunct motion in either case.

At mm. 325-326 the bass line drops out for two measures as the melody becomes momentarily more repetitive and urgent. The final third of this section, mm. 327-386, has two harmonies per measure, and the bass line pattern is much the same: every eighth half-note has an A in the bass, harmonized alternately as A Major and D major, and in between the bass line descends and ascends in equal intervals in each direction: all half-steps at first, then a variety of step sizes to accommodate the larger intervals traversed.

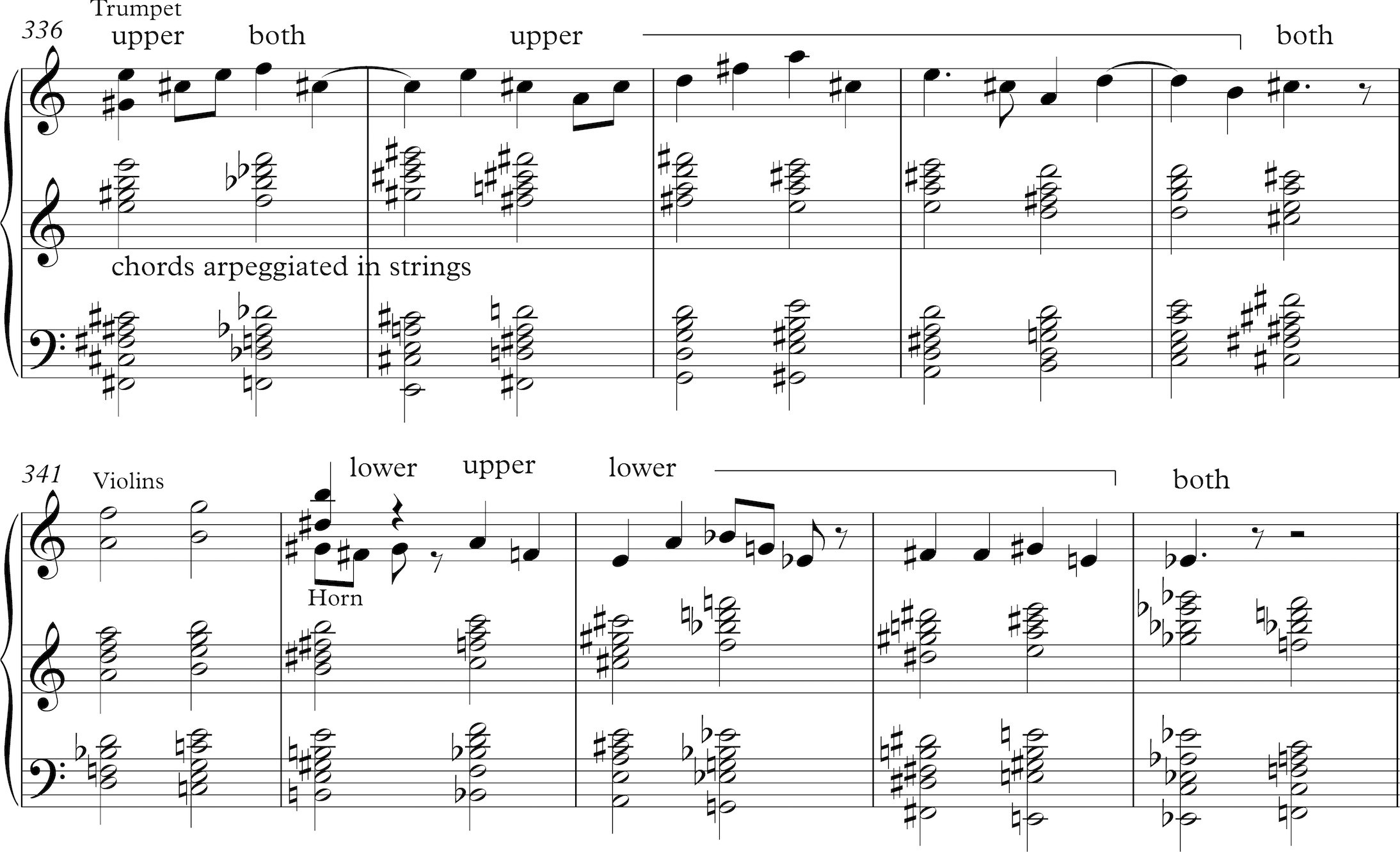

It is the rather wayward melodies in the winds and brass floating amid these chords, of course, that give the passage its delightful character. They seem to have been drawn from the available notes in the chords, and since each chord is the result of two triads, they sometimes follow the lower chord and sometimes the upper, often with cheerfully bitonal effect. In the following passage, for instance, which will stand in for many, the trumpet line at m. 336 mostly follows the upper chords. It seems to be in A major, but is inflected by the Db and Bb triads in the second half of m. 336, and it remains cheerfully dissonant against the lower chords. It resolves, though, on a C#, the only pitch shared in common by the F# major and A major triads of m. 340. And then the horn mostly follows the lower triads, seeming to continue in A major with one Eb triad thrown in - but its final Eb, the only pitch in common to the Cb and Ab major chords which accompany it there, feels like a resolution nonetheless.

The final part of the Pastoral section, mm. 387-415, is transitional, and seems designed to impart the Pastoral section's energy to the upcoming Fugue. As the previous bass lines moved upward and downward in ever-faster curves, here everything is either going up or down. The woodwinds grab the ball and start running nonlinearly up and down in parallel triads as the strings keep the rhythmic momentum ebbing and swelling with syncopated pizzicato chords.

Three times the woodwinds run from their low to high registers and come down again. Their last descent is interrupted by three dramatic arpeggios in the strings (now arco), whose peculiar interval patterns are rather delightfully determined by the rolling wind triads they happen to coincide with. And the last such descent lands emphatically on the D that opens the Fugue section.

I have always loved the Fugue - but it is no more a fugue than I am the Duke of Salisbury. The fugue "subject" comes to a definitive halt, and while there are many subsequent statements with various accompaniments, there are no perceived continuations of the original line as another statement of the subject comes in. Harris certainly knew what fugues were, and could write them. The year previous he had written his beautiful String Quartet No. 3 as four preludes and fugues, and he was enough of a Bach fanatic that he convinced his wife Beula to change her name to Johana in his honor! So I consider attaching the label to this texture of recurring motives not so much a mistake as a flight of fancy, or a wish that we try to hear the section as inspired by fugal process.

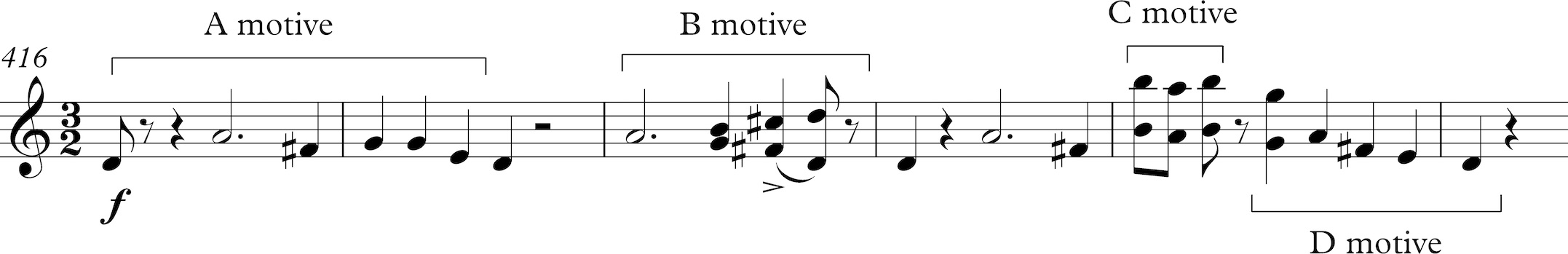

The fugue theme (I think we need not call it subject, since it has an end as well as a beginning) is perhaps Harris's best-known tune, and it contains four motives that will receive independent treatment, which I will label A through D.

Overall the section contains six statements of the full theme, all on D, G, or Bb. We can quickly divide the section into four rather obvious parts:

Four statements of the theme, with connecting material --- mm. 416-448

Canonic development of the A and B motives --- mm. 464-504

Reminiscence of the Lyric section --- mm. 505-527

Recapitulation of the theme turning into a transition --- mm. 528-553The A and B motives take on thematic and even canonic significance in the second of these sections and the B motive a little bit during the Lyric section reminiscence. The D motive is used as an occasional phrase-connecting device, and the C motive becomes a generator of accompanying texture. We can give a more detailed scheme as follows:

mm. 416-421 Theme in D

mm. 425-430 Theme in D

mm. 434-439 Theme in Bb

----- mm. 441-442 D motives

mm. 443-448 Theme in G

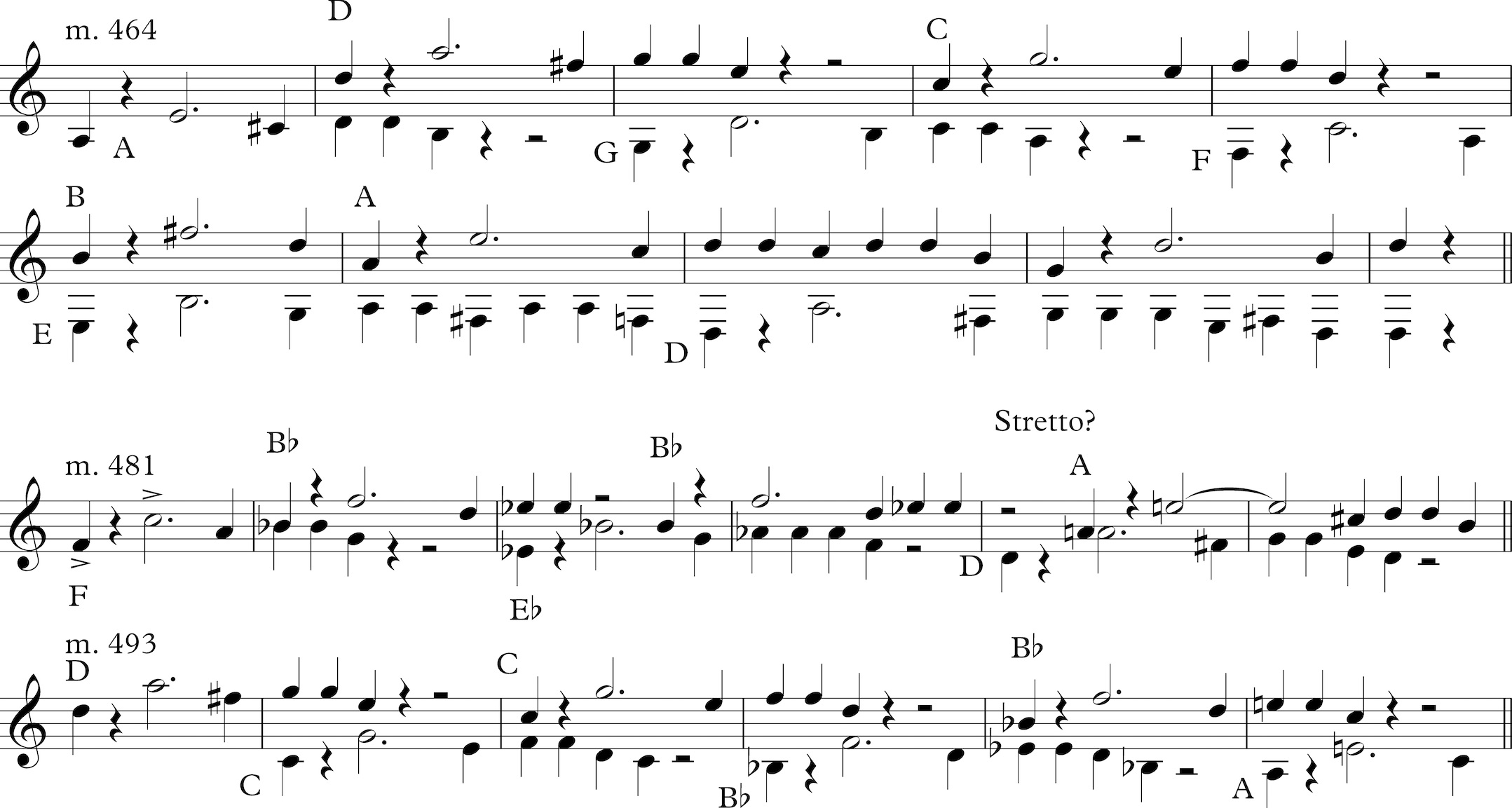

----- mm. 464-472 A motives interlocking on A, D, G, C, F, E/B

----- mm. 475-487 B motives overlapping on B, Bb, B, Bb

----- mm. 481-486 A motives interlocking on F, Bb, Eb, Bb, D, A

----- mm. 487-491 B motives interlocking

----- mm. 493-498 A motives interlocking on D, C, C, Bb, Bb, A

----- mm. 499-504 B motives overlapping

mm. 505-527 Reminiscence of the Lyric section

----- mm. 513-516 B motives in the Lyric material

----- mm. 521-522 B motives in the Lyric material

mm. 528-534 Theme grand statement in Bb

mm. 536-542 Theme in G, accompanied by D motive counterpoint

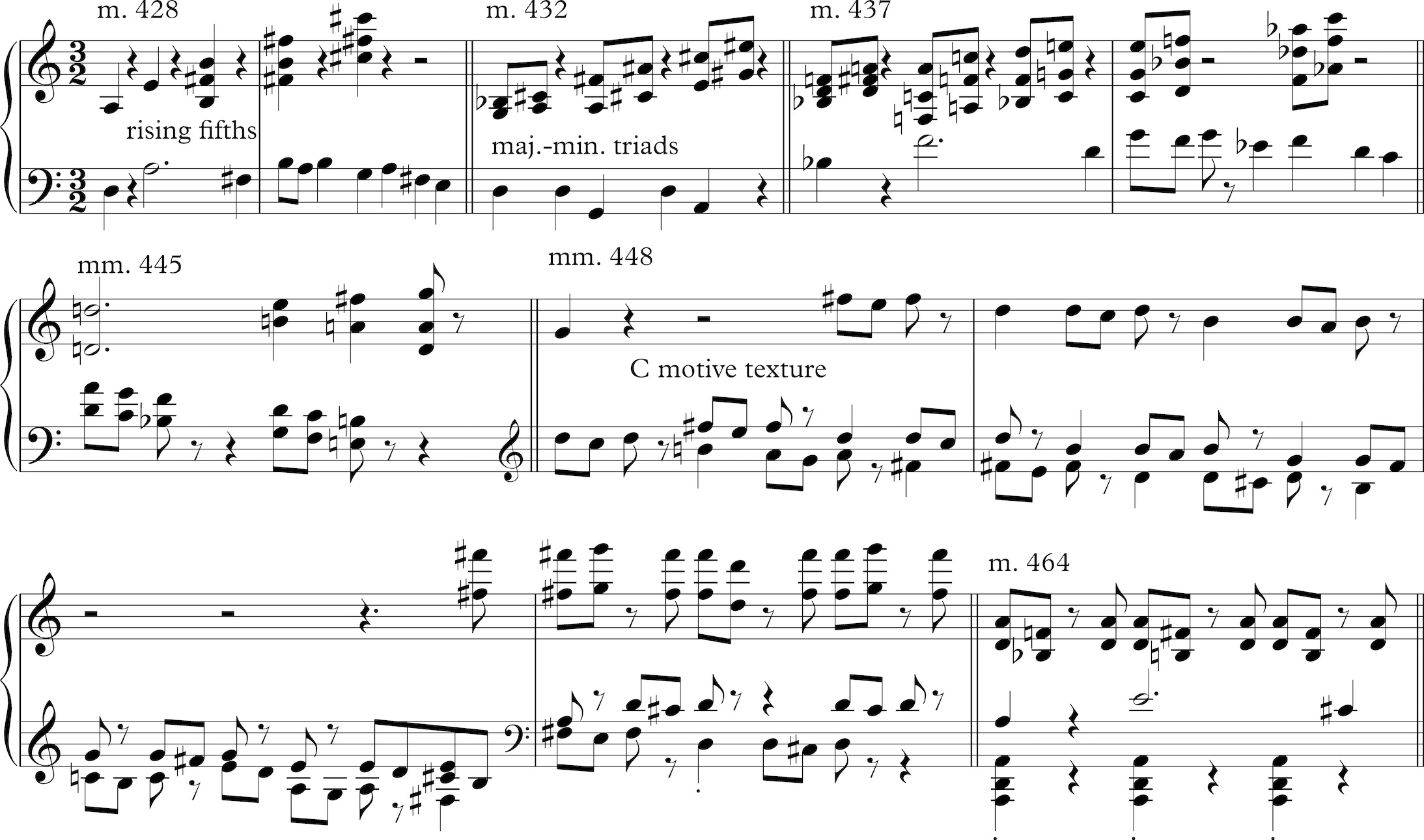

mm. 545-553 Partial theme in A devolving into B motivesThe connective tissue between the first two theme statements is the timpani, banging away on D, A, and G, and decrescendoing like an echo. A series of rising pizzicato fourths - continuing the sonic idea of the preceding transition - leads to a second theme statement, also in D like the first, and not like a fugue in which the subject immediately appears in a contrasting key. Aside from the thematic material, Harris's strategy in this fugue is to keep the rhythmic texture going by the repetition of rhythmic fragments that impose no necessity on the harmony, either because they are tonally static or because they fly by in such quick flickerings of bitonality as to not register. The next example shows six such figures which should enough to suggest the progression of the whole. In general, he starts from single chords, goes to eighth-notes in groups of two and then three, then overlapping them for a more continuous texture. There are at first chords rising by fifths (familiar from the Lyric section), then dyads in harmonically ambiguous relation, then triads in semi-parallel, then gestures of parallel fifths. It should be noted that the up-and-down motions of all these gestures continue, on however subliminal a level, the up-and-down feeling of the transition to the fugue in mm. 386-415.

At. m. 448 the texture begins to move toward harmonic stasis by overlapping the theme's C motives into a trilling continuum. The example above at m. 464 shows the endpoint of this stasis. Note that a D-A dyad is alternately followed by Bb-F and B-F#. These pitches refer back to similar ambiguities involving those notes in the introduction and Lyric section, and they will become even more prominent in the brass chorales of the Dramatic-Tragic section.

These motives and decorative figures, then, are the liquid suspension in which the thematic material floats. The D motives sometimes aid in transition, as the one at m. 433, ending on the tonic D, allows for its reinterpretation as the theme enters again in Bb; it recaps that role at mm. 441-443. After the first four statements of the theme, Harris begins to play the A and B motives in canon with themselves. The music rather behaves for all the world as if he is showing off his contrapuntal mastery by creating canons from his materials at a variety of pitch and rhythmic intervals (and he had studied enough Renaissance polyphony and Bach to know the drill), but actually most of the canons are simply sequences descending by whole-step: not a criticism, but another sign that Fugue is a rather grandiose title. The A motive is deployed canonically at mm. 464, 481, and 493. The first instance follows the circle of fifths between the two voices (not always with consonant results). The other two, briefer, are less regular but still sequence downward by step. Only at the end of the second such passage is the rhythmic interval of imitation shortened to less than a full measure.

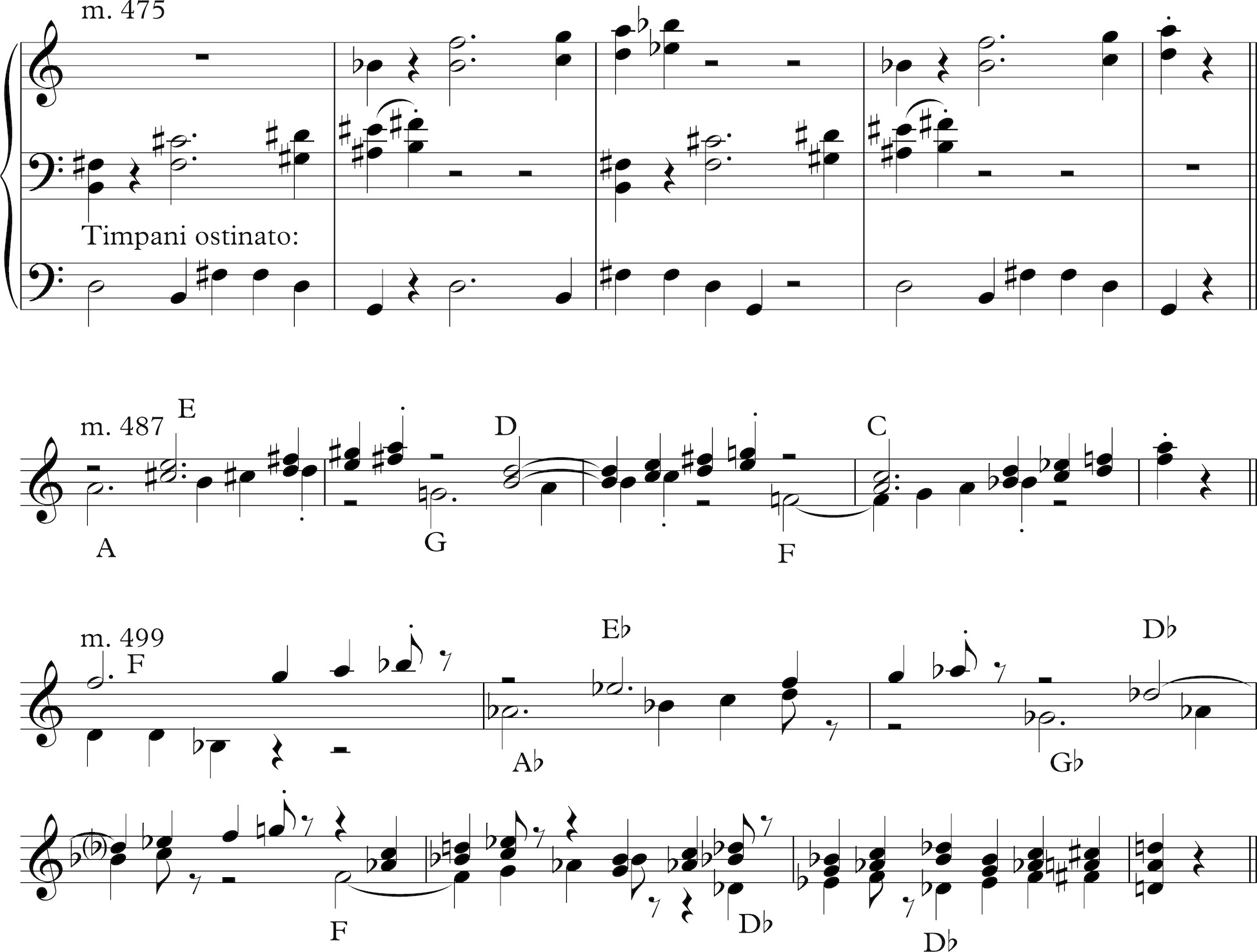

The canonic treatments of the B motive come at mm. 475, 487, and 499, and the second and third are continuations of the second and third A motive canons above. The first comes above an engaging ostinato drawn from the A motive in the four timpani (and I've always thought I would love to learn timpani only to play this piece). The other two use a half-note as the rhythmic interval of imitation, and also sequence downward by step, the final one devolving into three-quarter sequences that transition to the Lyric section reminiscence.

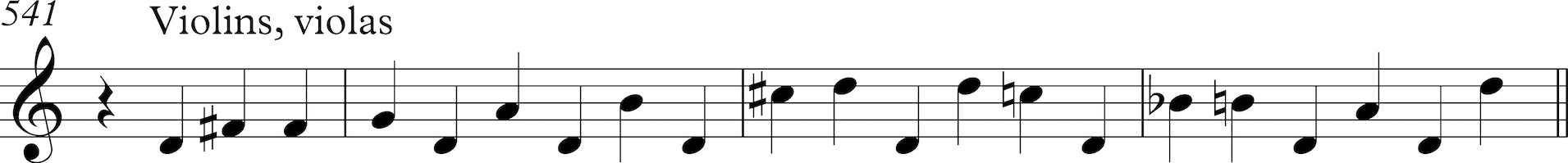

The reminiscence of the Lyric section begins abruptly, and what it consists of is that the woodwinds all play different triadic melodies as the brass outline octave-leaping motives, now in quick half-notes rather than slower quarter-notes; and that the harmonic rhythm shifts in six-beat phrases, as happened at m. 180ff. Harris's new motive seems to fuse the fugue theme's B motive with the Lyric section's triadic leaps.

The brief development of this motive (mm. 513-528) is too clearly audible to need explication, and it leads to a grand recapitulation of the fugue theme in Bb, given climactic emphasis by a flourish in the strings on its first note. At the theme's close its final D motive gets picked up by the strings and later winds in modulating two-part counterpoint that forms a background for a final full statement of the theme in G (m. 540).

This rather morphs into a new melodic idea based on a pedal point for increased intensity.

The final fugue theme in A breaks off and begins sequencing its B motive upward by step, and the reduction of this motive to its last three notes crescendos to a climax.

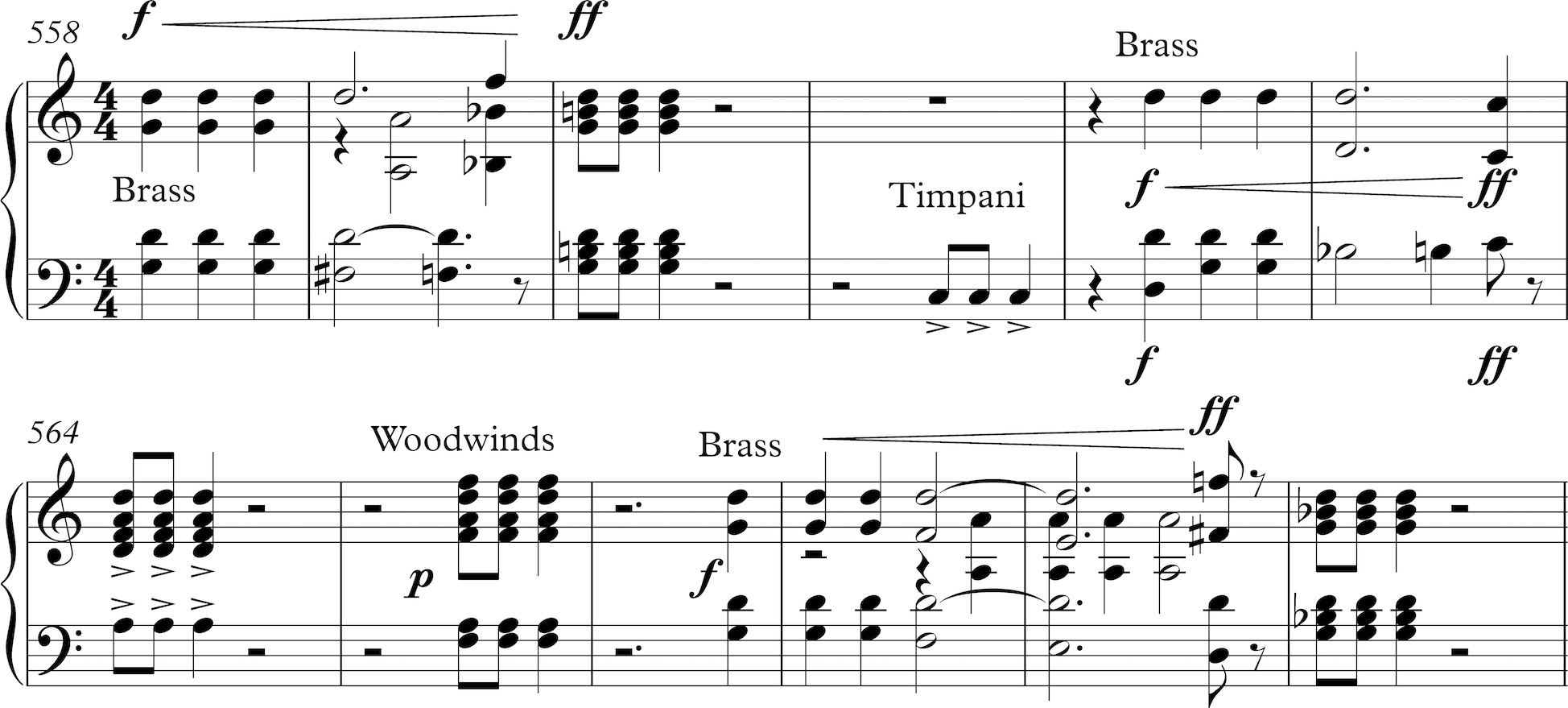

At m. 554 the fugue momentum comes to an abrupt halt, and the brass break out in a series of fanfares whose characteristic rhythms - a triple quarter-note upbeat to a longer note and a concluding rhythm of two eighths and quarter (still recalled as the fugue theme's C motive) - will punctuate the first half of the Dramatic-Tragic section.

Tubas, basses, and timpani wrench the tonality down to Eb, and the Dramatic-Tragic section begins.

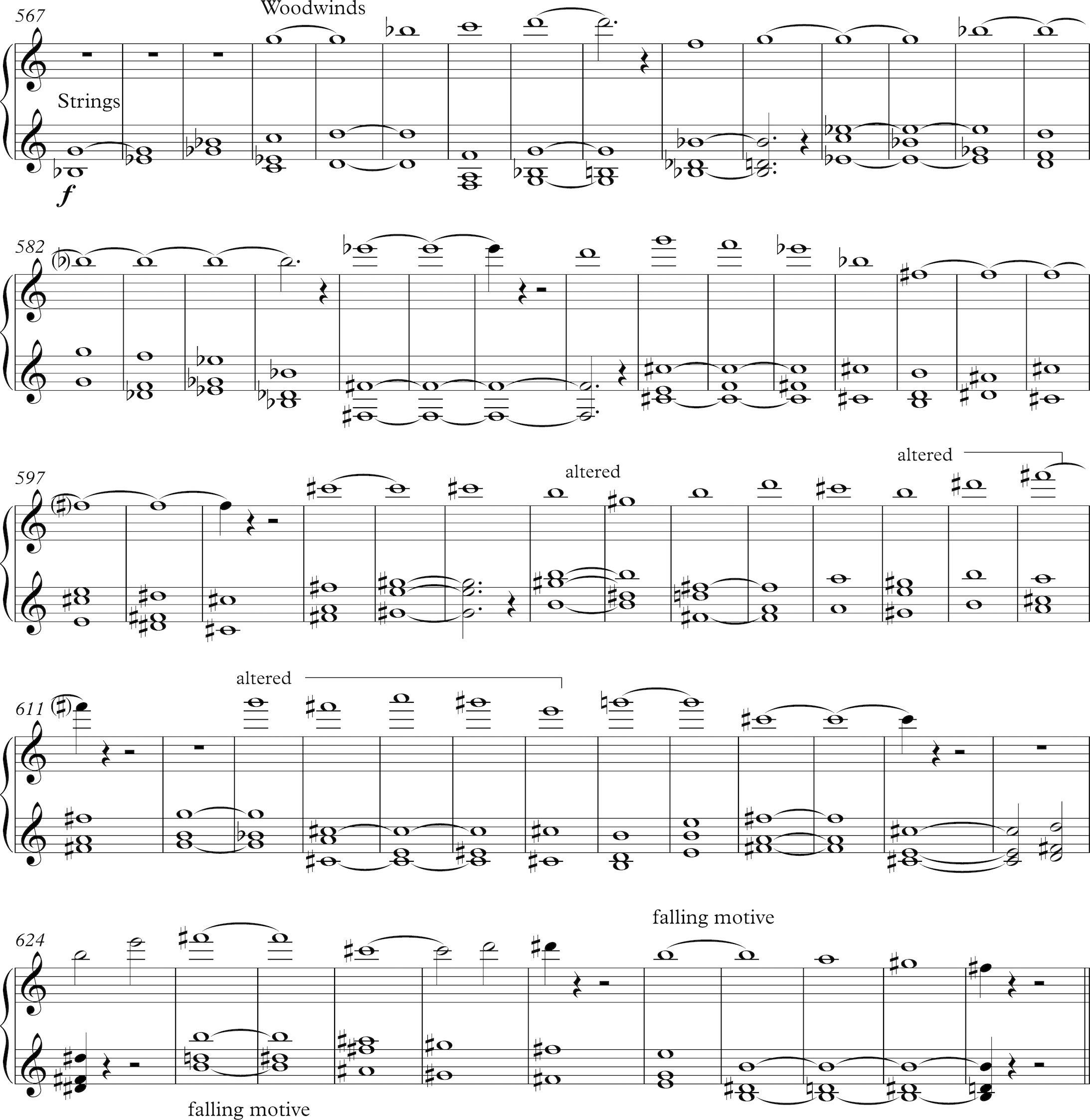

The first half of the Dramatic-Tragic section is a canon between the strings and winds on the main theme, followed up through the falling motive. The canon is at the octave, and is a fifth higher than the statement in the opening Tragic section. While the woodwinds play their line in octaves, the strings add in internal notes that inflect the harmony. Starting at m. 604 some of the intervals in the woodwind line are altered, presumably for harmonic reasons, and the notes in the winds are sometimes extended longer than in the strings, so that while the winds start three measures later than the strings at the beginning, they are five measures behind when the passage comes to a halt. The alterations suggest that Harris did not write the theme with canonic treatment in mind, and that he used the juxtaposition of the two lines to suggest harmonies as he went, sometimes changing notes in the winds to get the kind of harmony he wanted.

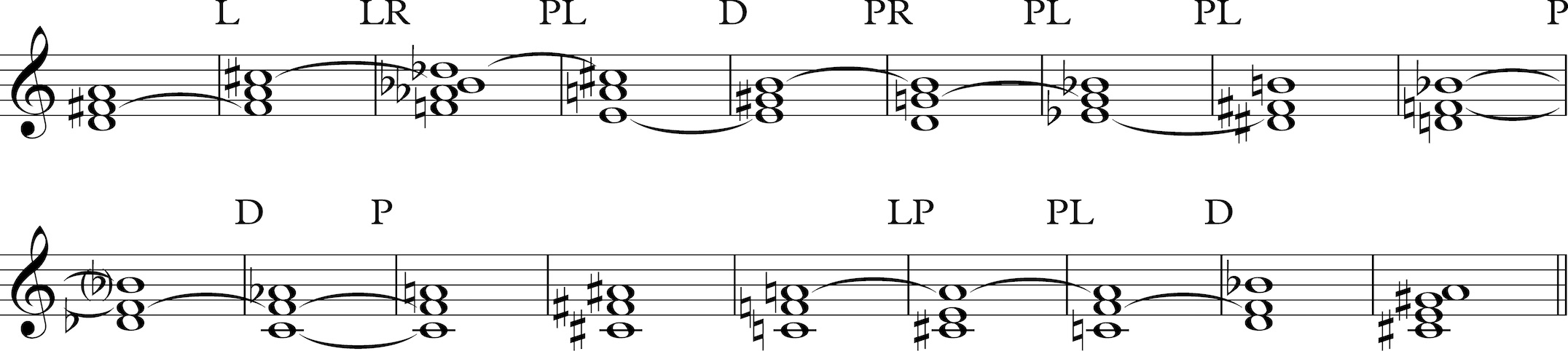

The entire canon is punctuated by brass and timpani playing the fanfare's two rhythmic motives, following the canon's harmony wherever it leads. The typical example below includes pivot notes between harmonies and Neo-Riemannian symbols for the transformations.

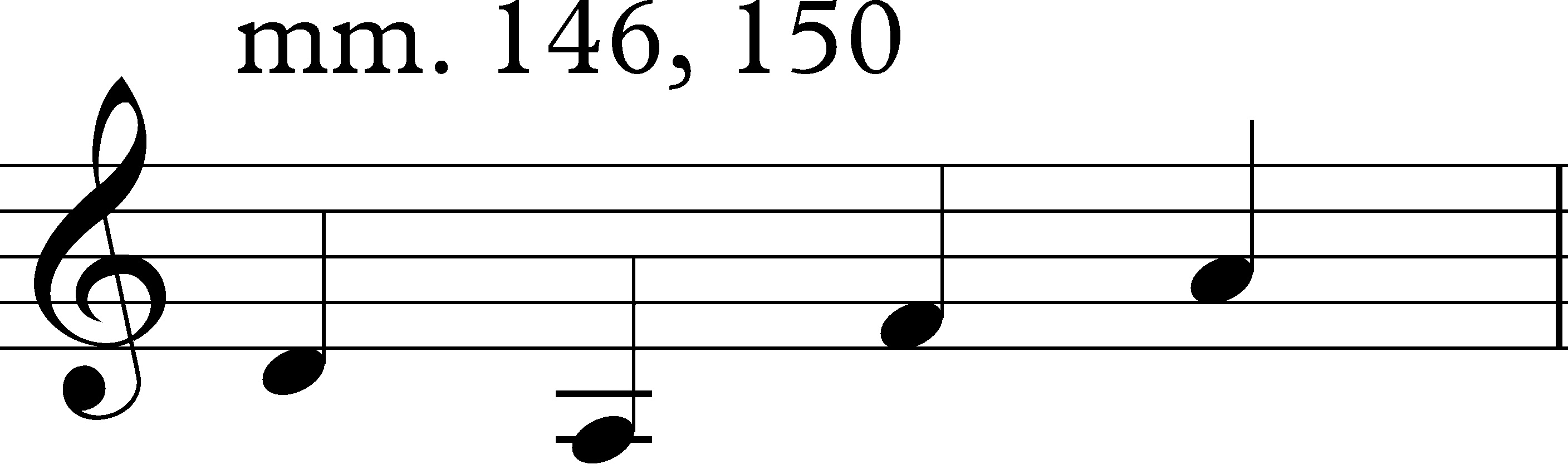

Following the freely modulating grandeur of the canon, the unutterably sad conclusion to the Dramatic-Tragic section, marked "Meno Mosso, Pesante," narrows down to the key of D and contains only five elements. One is a steady, half-note drum beat on a timpani D pedal point that runs for 53 measures, mm. 634-686. The second to enter is a series of chorale phrases in the trumpets and trombones, each starting melodically on D and descending to A. The triads (and only one chord, at m. 660, is not a triad) include minor triads on B, Bb, A, G, F#, F, Eb, and D, with major triads only on Bb and Gb. I mark them here with neo-Riemannian transformation symbols to show the mostly consistent nature of the voice-leading, though when you get to combinations like PRLR and RPRP it is evident that Harris is no longer thinking in terms of pivot notes.

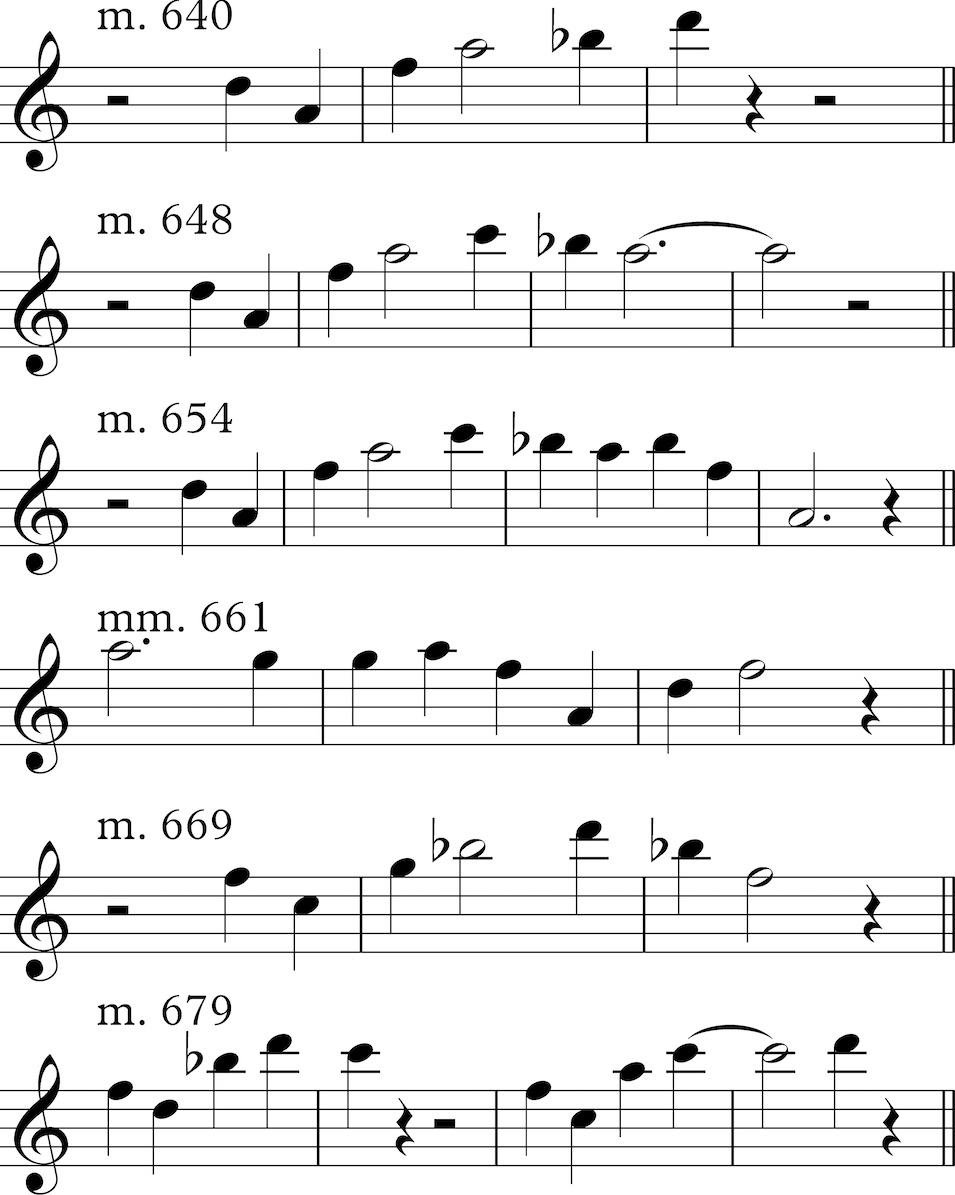

The third element to enter is a series of iterations of the falling motive from the main theme, with minor variations, in the bass clarinet, bassoons, tubas, and double basses, starting at mm. 638, 646, 651 (all in the D major scale) and at 660, 668, 676 (these last three in the minor scale).

The fourth is a series of phrases derived from the lyric theme in the horns and upper woodwinds.

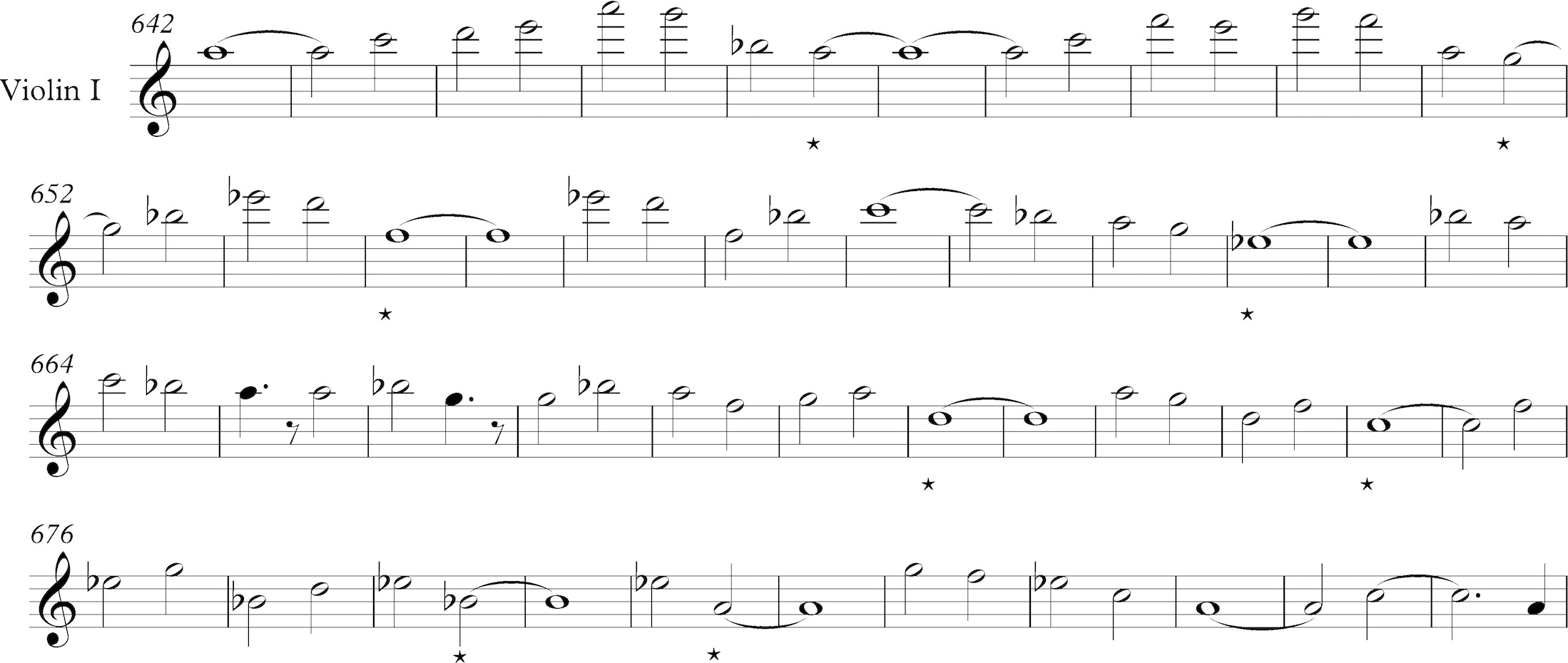

The entire passage is held together by one of Harris's long, "autogenetic" (as he called them) melodies in octaves in the violins and violas, entirely in D Phrygian mode except for one E-natural (which is also the G minor scale, the key in which the piece will end), and generally descending in stages by two octaves. Note that the long low notes in each phrase, marked here by asterisks, move resolutely down the scale.

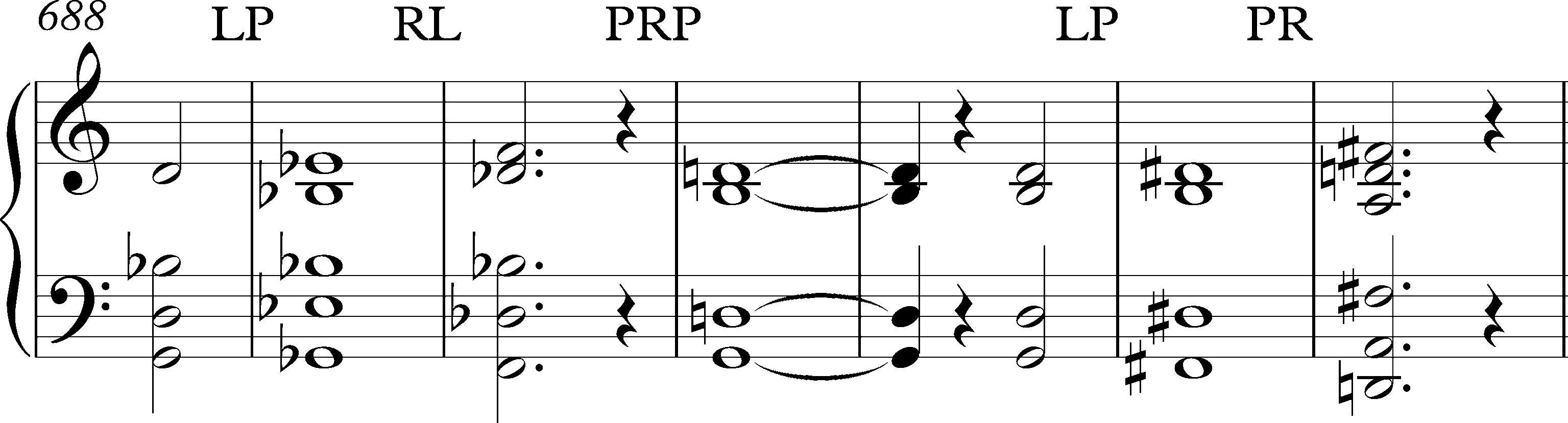

At last the music pauses for a dramatic series of chords in the tutti orchestra, in a progression all in neo-Riemannian voice-leading.

The silence that follows is broken twice by bursts of timpani on G and D, with blasts of G and C in the horns and trombone, and then an F#-C# dyad leads to a final, bitter G minor triad sustained to maximum intensity.

A significant key to this symphony's success is its formal balance, which makes its very shape more memorable than that of any of Harris's other symphonies (though two of the latter I have to judge only by reputation). Consider again the Tragic/Lyric/Pastoral/Fugue/Dramatic-Tragic sequence. The Lyric section is recalled in the second half of the Fugue section, and their motives start to fuse. The main theme of the second half of the first section, played once by the strings and once by the woodwinds, becomes the structural framework for the first half of the final section, in canon between those very instruments. Because of this the Tragic and Dramatic sections are marked by a great fluidity of tonality, unstable but held in place by the main theme - until the denouement, in which the music focuses on a 53-measure D drone before ending in G minor. In contrast, the Pastoral section is structurally static, anchored around A, then Ab, then A again - even though its momentary harmonies range all over the scale. The up-and-down movement of the Pastoral bass line expands and continues through the Fugue's accompaniment. The introduction's melodic twists prepare the way for the Lyric section's melodies, which recur as a decorative ingredient of the Dramatic section, and the neo-Riemannian progressions of the denouement seem to absorb and focus the melodic tendencies of the introduction and Lyric section. The main theme's falling motive comes back again and again as a kind of universal ground bass. Each new section draws energy from its predecessor. No element, once introduced, ceases to remain an element of subsequent events - except for perhaps the fugue theme, which is foregrounded as the focal point of the work. It is rare that any composer, of any era, happens upon such an organic balance of contrasts and similarities, and hardly surprising that he could never quite achieve it again.

Copyright 2019 Kyle Gann

Return to American Symphonies

Return to the home page