Naive Pictorialism:

Towards a Gannian AestheticBy Kyle Gann

In 1989 John Rockwell reviewed a concert of my music in the New York Times and described my music as "naively pictorial." He meant it for disapproval, I guess, but I became very excited when I read it, because it proved that the essence of my music was getting across.

I always try to include a large element of naivete in my music, and I often try to tell a story that will be intelligible to the listener. There is a great risk involved in trying to write naive music: your fellow composers are likely to jump to the conclusion that you are naive. But it is a risk that must be taken.

Losing touch with naivete was the great disaster of music in the 20th century. It created a vast gulf between modern music and the rest of the world. It was ideologically motivated. It was humanly unnecessary.

Each of us comes into the world and quickly gains, as a child, from observation and participation, a certain naive view of what music is, what it can express, how it expresses, and how people enjoy it and react to it. No matter how contextually conditioned, there is something rock-solid and irreproachable about this pre-verbal naive impression.

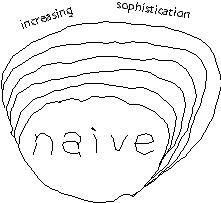

Some of us enjoy music so much, or become so bothered or fascinated by it, that we begin studying it, perhaps going to music school. In this process, our perception of music becomes more multifaceted and subtle. We learn to hear large-scale structure, nonobvious pitch relationships, various degrees of harmonic intensity, references to other works of music, other styles, other historical periods. We learn to notice the recurring major-third modulations in a Mahler symphony, the inversion canons in Webern, the complex harmonic consistency in a piece by Boulez. Layer by layer, we vastly increase our sophistication in the number of levels and the amount of detail with which we can hear music. This is all completely good.

The problem is that some young musicians make a simple mistake. They get the idea, and often professors encourage this idea, that as you move to the next level of sophistication, you should leave the last level behind, and repudiate it. As they learn to appreciate Mahler, they forget why people are attracted to Dvorak. They learn to listen to late Webern as an example of classic order, and no longer perceive the very obvious chaos on the surface of Webern's music. They learn to appreciate rhythms of 18 against 19 against 20 in Nancarrow, and forget why people like to move to 4/4 meter. They learn to focus on the structuring processes of music, and forget that for the vast majority of the earth's human beings, structure is something arcane, a professional matter that composers are not supposed to bother them with, while atmosphere, regularity or irregularity of rhythm, and relation of pitches to a scale are very obvious and very important. These musicians come to live, in fact, on the sophisticated outer edge of music, and lose touch with music's central core.

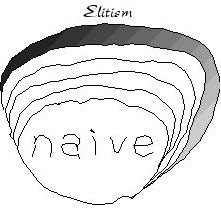

To live entirely on that sophisticated edge and never touch the naive center - this is a perfect definition of elitism. When your Aunt Ethel can hear that a Synchronism by Mario Davidovsky sounds anxious and weird and chaotic and you can't (no matter what more subtle things you've learned to hear in it), you've become an elitist. Naivete is the antidote to elitism.

Elitist musicians invariably become bitter, because they are separated off from the rest of the world. When they make their judgments about music, they are right - but being right is a barren consolation when 1. you have so narrowly defined your terms that no one can argue with you, and 2. you have so retreated into a specialized vocabulary that only a few colleagues can still understand you. And on many larger musical issues they become wrong. They are right when they insist that the musics of Elliott Carter and Milton Babbitt are brilliant in their structural intricacy, but the world is also right in noticing that those musics express (however unintentionally) a kind of unnuanced anxiety and confusion. And the sophisticated musicians who have lost touch with naivete and claim, "No, no, music is just an assemblage of notes, it can't express anxiety" - are simply wrong. Wrong because they flatly deny a universal perception (even if it's a culturally conditioned perception, where does art take place if not in a culture?). They are, in fact, in a funny kind of way, naive.

It is academically naive to expect that your intentions will automatically come through in the music with no special effort on your part. It is the composer's job to make his or her intentions clear in the music. If you are trying to create an impression of disorder and confusion and the naive listener hears it as disorder and confusion, fine. But if you are trying to create symmetry, order, elegance and the naive listener's gut impression is one of disorder and confusion, then it's time for the composer to go back to the drawing board.

That's what separates the disorder of an Ives or a Cage from that of a Webern or a Babbitt: Ives and Cage intended to create disorder at times, and the naive reaction is evidence of their success. Webern and Babbitt, at times, intended to create order and symmetry, and the naive response is quite opposite. The Webern Symphony may, in reality, be quite elegantly structured. But art isn't about reality - it's about appearances. All that a composer gets to take credit for is the appearance of his or her music. The reality is for grad students.

Grad school tends to make composers (and the people who will become Uptown critics) very literal-minded, teaching them to insist on the reality and ignore appearances. The young composers remove themselves from the arena of art, since art is about appearances; they are no longer artists. Like Nietzsche's last man who was proud of his education, they become proud of their sophistication. They look down on any music that includes even a bone for the naive listener. But they should be ashamed to be so cut off from the naive wellsprings of all musical life.

To relinquish our sophistication is not the solution. The elitists think that that's what the minimalists and their progeny are trying to do. It is not. Very few composers (though there have been some like Cornelius Cardew, for political and ideological reasons) - very few composers want to abandon the advances in musical perception and technique gained in the 20th century.

In my opera Custer and Sitting Bull, I shift meters among 2/4, 11/16, 9/8, 13/16, 5/8, all over the place. Within those meters 16th notes will rush along at 13 in the space of 10, switching to 6 in the space of 5. The piece uses as many as 31 pitches per octave. It contains chord progressions that have never been used before. The number of composers in the entire world who could look at some of my microtonal chord progressions and understand what's going on could easily fit into a small auditorium (and has). No one could look at this score and perform these rhythms accurately, and I couldn't perform them myself had I not used computer sequencing to train me to play them by rote. This is not unsophisticated music.

And yet, what elements are on the surface of Custer and Sitting Bull? The 4/4 snare drum beat of the American military. The repetitively offbeat drumming of the Sioux Indians. Military trumpet calls. Native American flute melodies. The rhythm of words repeated over and over in an almost lulling effect: "Yes, but do you know who I am? Yes, but do you know who I am? Yes, but do you know who I am?" No ten-year-old child who's lived in the world could miss the narrative signs in this piece. The trumpet and snare drums denote the cavalry. The breathy flutes and tom-toms denote the Sioux Indians. The long-sustained, pulsating chords after the battle scene are the stillness of death. The last, lonely, suddenly unaccompanied snare drum beat is the final fading of Custer's ghost from this world. God, is it naive. And I've been pleased to see people deeply affected by it.

My Disklavier piece Texarkana is entirely in rhythms of 13 against 29 or 13 against 31, with various quintuplets thrown in, plus a constantly modulating collage technique. But the basic material of the piece is ragtime rhythms and harmonies drawn from the style of stride piano king James P. Johnson, lots of tonic and dominant with secondary dominants. The familiar harmonic relationships give the listener something naive to hold onto through the undefinable rhythms and stream-of-consciousness form.

My quintet Hovenweep starts with a long, strange chorale that glides through constantly changing beats. But the one element that emerges to dominate the last section is a naive little rhythm present from the first measure on: an eighth note followed by two 16ths.

Sometimes I succeed at finding and exposing that naive element better than others. It's always a struggle. It's the struggle of the piece.

Because for the trained musician, achieving true simplicity and true naivete are not easy. There are so many things one could do. One has learned so much. It is so easy to work out a theoretical idea, so much more difficult to polish a musical passage until it can gel into an indivisible unity in the listener's memory. It is so easy to add another layer of complexity, and another and another, until the original point is obscured. But to add layers of complexity and yet have the final result so simple and clear than even a child could understand it - that takes a tremendous toll in hard work and self-criticism. It requires nights of despair, listening to the results and saying, "No, no, that's not it yet." It requires leaving behind delicious techniques that one worked hard to acquire in school, because they obscure the desired effect. It requires forcing all your hard-won learning into an intermittent and subservient position, and keeping your imagination constantly at center stage. It requires composing with your ear, and telling your brain, "Don't call me, I'll call you." It requires a leap of faith that somewhere that naive element is in there, and that it will emerge and save your sorry ass at the last minute.

Is there anything in the world easier than writing complicated, enigmatic, ambiguous music? I've known freshman music students who could do it.

I was brainwashed twice in my life, once by the Baptists, and once by the 12-tone priests. During the late 1980s, a few years past my doctoral work, I went through a difficult transition in the way I listen to music, and afterward resumed a career as a composer that had bogged down. I had been trained to hear and follow changes of hexachord in a 12-tone piece. I could listen to a symphony by Schubert and follow the modulations and always know what key I was in. But I gradually came to feel that I was missing something in the music I was listening to. It was becoming dessicated, a kind of exercise of constantly active attention. All music had become expressively interchangeable. Imagine listening to a Billie Holiday record and mentally grouping the notes of each phrase into pitch sets - that's pretty much what I had been trained to do. With some effort, I quit focusing so much left-brain analytical attention on music. I began listening to music more emotively, more the way I had when I was young. I began enjoying more different styles for what they could offer. I began composing better again. And in the course of all this, I lost an ability I had once successfully cultivated - the ability to tell one 12-tone piece from another.

In school I had studied Bartok, and Schoenberg, and Webern, and Boulez, and Stockhausen, and Babbitt. (I still teach all that stuff, not as examples of what to do, but as examples of what's already been done and therefore doesn't need to be done again.) I learned all kinds of things like golden sections, and the Fibonacci series, and elegant things to do with tone rows, and how to do stupid pitch tricks with pitch sets, and how to isomorphically transform one musical structure into another, unrelated-sounding musical structure. And by divine grace, I quit using any of those things in my music around 1987. Now I try to write music in such a way that when I finish a score I can look through it and say with satisfaction, "Nope - not a thing in there for the grad students. It's all for the listeners."

The music of a trained composer should be sophisticated, but the devices that attest to that sophistication belong in the background. I am delighted to be frequently told that people often listen to my 31-pitch-to-the-octave music without realizing it's microtonal. I don't use microtones to make my music sound weird, but to subtly increase its power. The complex rhythms, the subtle pitch relationships, the underlying structures in my music are there to give the music deeper coherence, to create a richness that will provide continual discovery on a multitude of listenings. But it is not my business to bother, or impress, or oppress the listener with those complexities. The road leading to that sophistication starts, for the listener, with the recognizable, naive musical icons on the surface. Something on the surface of the piece has to ring a bell with every listener in the audience, so that every listener has something to grasp onto.

It is a wonderful thing to stretch the ear, to increase people's sensitivity to what can be heard, to multiply and expand the numbers and types of pitch and rhythm and formal relationships that can be heard. But to stretch the ear, you first have to grab it. You don't just hold your hand in the air and demand, "Stretch out to here."

There is nothing wrong with writing the occasional completely intellectual piece for the delectation of one's colleagues: Beethoven's Grosse Fuge, Bach's The Musical Offering. But to devote one's entire career to such pieces is to indulge a life of arrogant masturbatory delusions.

On December 28, 1782, Mozart wrote to his father about the new piano concerto he was working on: "There are many passages here and there from which connoisseurs alone can derive satisfaction; but these passages are written in such a way that the less learned cannot fail to be pleased, though without knowing why." The "artless art" that Mozart championed is precisely the attitude of Totalism, the movement in New York music that I've been associated with. Totalism denotes having your cake and eating it too: having enough recognizable fun and beauty on the surface to entice amateurs and enough sophistication in the background to fascinate cognoscenti.

All the microtonal complexities and humanly unplayable rhythms are a lot of fun, and they keep my brain entertained while my ear is busy composing. But the most important part, the part that empowers music to resonate through society and enables one to "speak truth to power," that part that will make your work dangerous and threatening to bureaucrats and academics, the part that will make you despised by keepers of the status quo and loved by generations yet to come, is the hardest part to achieve: the part that is naive.

December, 2001

Copyright 2001 by Kyle Gann

Return to the Kyle Gann Home Page

If you feel moved to reply to any of this, email me