Virgil Thomson: Symphony on a Hymn Tune (1926-28)

Analysis by Kyle Gann

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 3.0 License.Is there another symphony in the repertoire so little in need of explication as Virgil Thomson's Symphony on a Hymn Tune? A child could understand it; the musically educated person puzzles over it. Thomson (1896-1989) had spent the 1920s in Paris distantly orbiting Erik Satie (1866-1925), the composer most associated with the nonsensical Dada movement of the post-WWI years, and had known the Cubist and Surrealist painters who were also involved. Immersion in such a milieu instilled in him a permanent disinterest in logic and linearity. The Symphony on a Hymn Tune (the first three movements written in 1926, the fourth requiring cogitation until 1928) is something of a collage made of largely simple and static figures. Parallels can be found in Stravinsky's music as well, but the Russian master's brooding and dissonant textures bear little similarity to Thomson's insouciant bitonality and affectionately comic evocations of small-town America. A composer complained to Aaron Copland that Thomson's music was "dumb," and Copland replied, "But it's intentionally dumb - he's the American Satie."

Despite his Parisian polish, Thomson was from Kansas City, Missouri, and the symphony seems like an offbeat depiction of small-town American life in a simpler age. "How Firm a Foundation" is the hymn tune of the title, but it is also joined by other tunes that would have been familiar from Thomson's youth. Several ideas recur collage-like from movement to movement, so much so that I knew the piece for years without having much idea where one movement ended and the next began. I have had the rare luck to hear this symphony live in the concert hall, where the sparseness of its orchestration comes as a shock. One doesn't notice so much on recording, but watching an entire orchestra sit there as a single trombonist, flutist, and violist trade solos for a long time, or the brass play the same languid chord fourteen times in a row, provides as visceral a Dadaist gesture as one will find in the symphonic repertoire.

Thomson's Second Symphony (1931) is an arrangement of his First Piano Sonata, and his Third (1972) an arrangement of his String Quartet No. 2, though it contains music from his late opera Lord Byron. Both are likewise simple and tuneful but without abundant quotations and neither as cheeky nor surreal, nor have they been as successful in concert life, as the Symphony on a Hymn Tune.

Despite discontinuities in tonality and texture that forestall any conventional sense of dramatic sequence, the Symphony displays a simple unity by use of the hymn's opening pentatonic notes E-F#-A, and by other melodies deriving from a do-re-mi or sol-fa-mi motive.

First movement

(keys in parentheses are not supported by key signature)

Introduction in fifths -- mm. 1-20 -- A major

How Firm a Foundation -- mm. 21-38

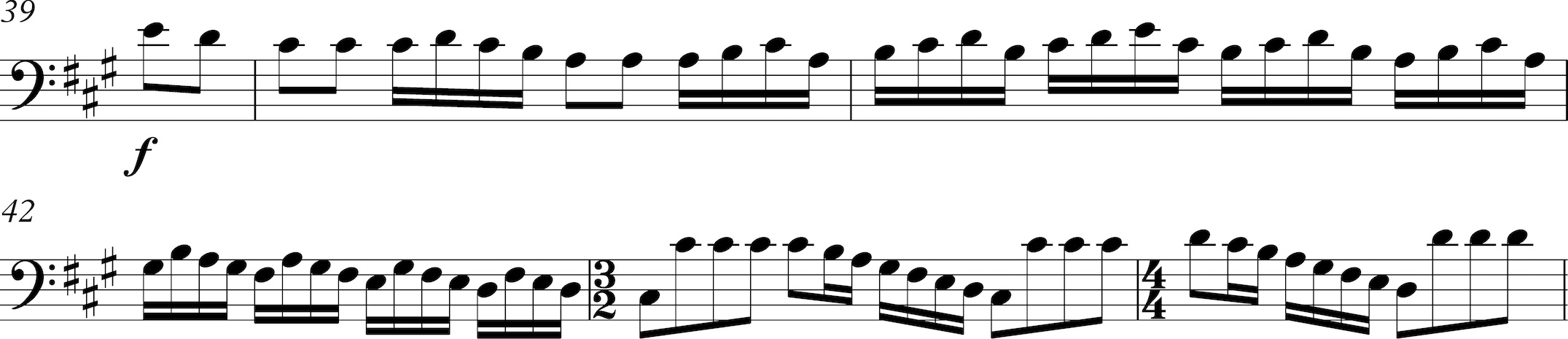

How Firm 3/4 Variation -- mm. 39-61 -- G major

Yes Jesus Loves Me -- mm. 62-72 -- (Ab major)

How Firm 3/4 Variation -- mm. 73-94 -- G major

---- Yes Jesus superimposed -- mm. 87-93

Simple dance tune -- mm. 95-106 -- (D major)

Syncopated theme -- mm. 107-123

---- Fifths interruption -- mm. 113-114

---- Fifths superimposed -- mm. 118, 120, 122

---- Yes Jesus imposed -- mm. 121-123

Syncop. tune in 3rds -- mm. 124-165

---- Fifths superimposed -- mm. 134-138, 140-148

Introduction recap -- mm. 166-183 -- A major

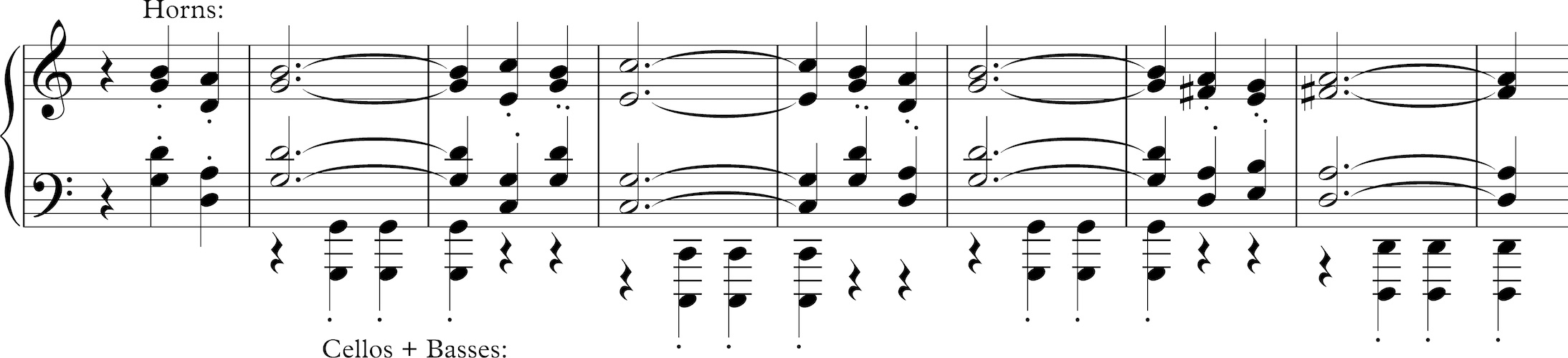

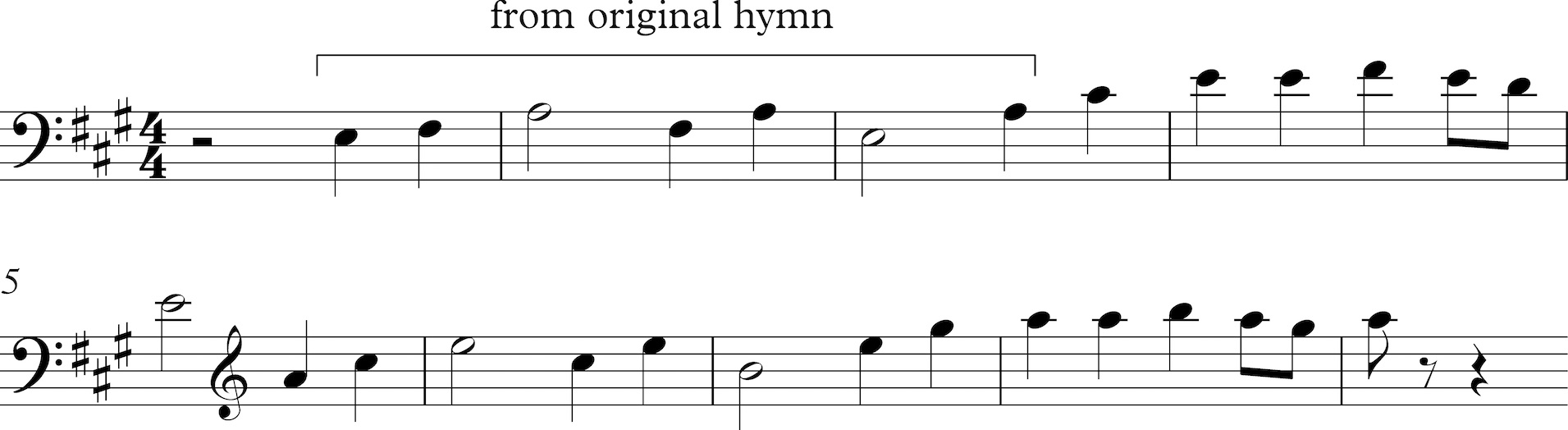

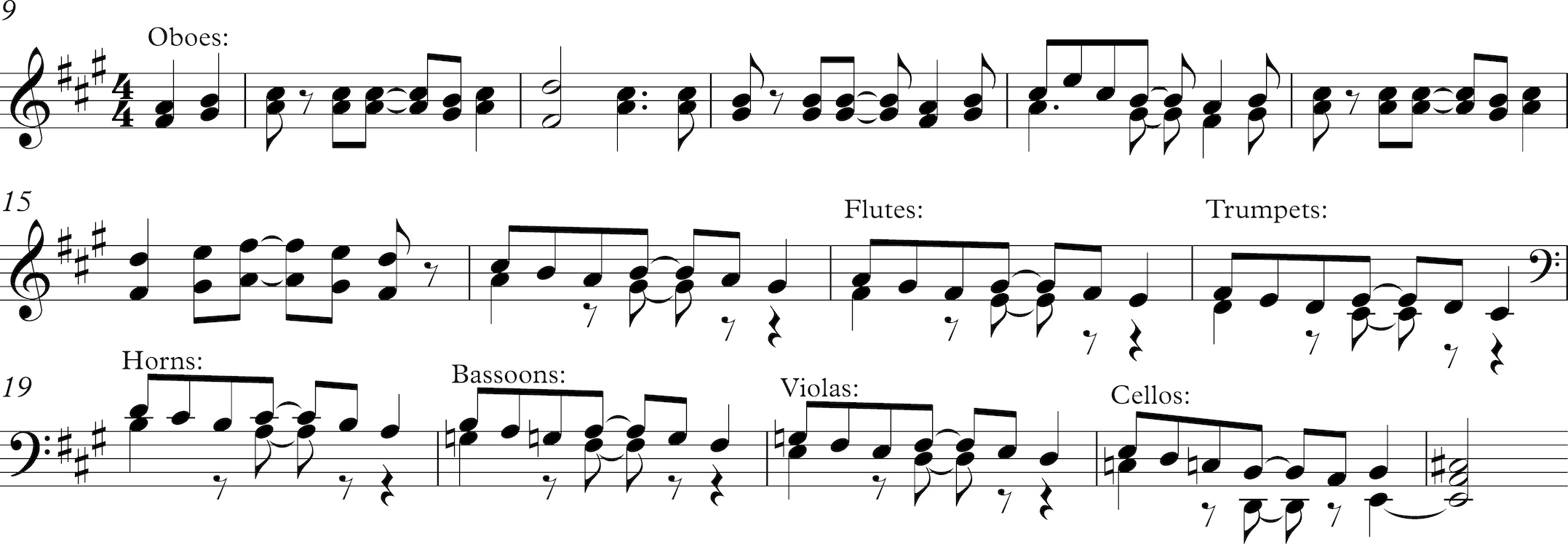

Cadenza Obligata -- mm. 184-233 -- (variable)The first movement opens with a set of spare parallel fifths in the horns, a line that will appear in several movements, perhaps interrupting another melody or hovering menacingly in the background. Three such pairs of mostly parallel lines are heard in sequence, in the horns, flutes, and bassoons, separated by a growling low C in the strings, a dissonant dyad in the trumpets.

Finally (m. 16) a solo trombonist plays a solo beginning with the first three notes of the hymn tune of the title - "How Firm a Foundation" - in the key of A-flat, devolving into a comic trill. And then, the string orchestra devoutly launches into a quiet and, at first, respectful reading of the hymn itself, in the non-sequitur key of A major. Thomson alters the traditional melody only slightly, at the notes marked by asterisks, where his tune dips only an elegant major second instead of the more rustic major third. When the winds take over the third phrase, though, the horns and bassoons playing the tenor and bass lines slide down a sequence of parallel fifths in the wrong key, as though still influenced by the trombone solo. (Also notice at the plus sign the alto voice that refuses to resolve correctly.)

As though in a theme and variations, the hymn is immediately followed by a variation of it, in 3/4 and in the key of G. The waltz accompaniment in the lower strings oddly has an F# on every downbeat as a kind of appoggiatura.

But this is a symphony on not just one hymn but two, because there are many appearances of a old song directed toward children called "Jesus Loves Me." Thomson uses only the song's final refrain, which was a late addition to the original hymn.

The 3/4 version of "Foundation" is interrupted by "Yes Jesus Loves Me" in Ab, though instead of giving the whole tune Thomson merely repeats the first two phrases. The violas and cellos add some bitonal lines in fifths.

Afterward, at m. 72, the 3/4 variation of "Foundation" blandly resumes as though nothing had happened. In mm. 87-93, the violins and flutes overlay "Jesus Loves Me" in Ab over the continuing trumpet variation in G major.

Thomson's next idea is a class of melody that he uses quite often, with myriad minor variations, which for lack of a better term I am going to call his simple tunes. These are melodies that consist of only a few adjacent scale pitches, in rhythms that are either very regular, interestingly syncopated, or both. Aside from the quoted melodies, they make up much of the symphony's continuity, and are particularly abundant in this first movement, from mm. 94 to 165. I list several here in the order in which they occur.

In this long section in G major, these simple tunes are often the foil for bitonal superimpositions of "Jesus Loves Me" in C (mm. 115-116) or in Ab (mm. 121-123) or the opening perfect fifths chant in Eb (mm. 110-114, 118-122, 140-144) or in D (mm. 134-138). Measures 145-148 are a tense, bitonal climax in which the simple tunes have devolved into a simple repetition of I and V chords in E major, while the winds play "Jesus Loves Me" in Ab, and the trumpets and trombones play the fifths chant in Ab and E respectively.

The following passage (mm. 149-165) returns to A major with the last of this movement's simple tunes, interrupted every now and then by an E-F#-A cadence in the brass. This gives way unexpectedly to a kind of recap of the introduction (mm. 166-183), with the same instruments involved but with slightly more elaborate orchestration.

The last fifty measures of this movement comprise one of the most eccentric gestures in any known symphony: a Cadenza Obligata for solo trombone, piccolo, cello, and violin. First the trombone reprises its hymn tune plus trill figure from the introduction, leading into a wandering melody. In its last few measures a flute enters, playing up and down virtuoso scales and leaping to a high C#-D cadence. By this time the cello has entered with a rambling tune in Eb, marked by glissandos. As it is ending the violin comes in with a cadenza that defies general description. At last all four instruments are playing again, and start repeating a clashing figure.

A cadenza would seem to imply the eventual return of the orchestra before movement's end, but instead the percussion merely grumble with a tremolo to maximum crescendo.

Second movement

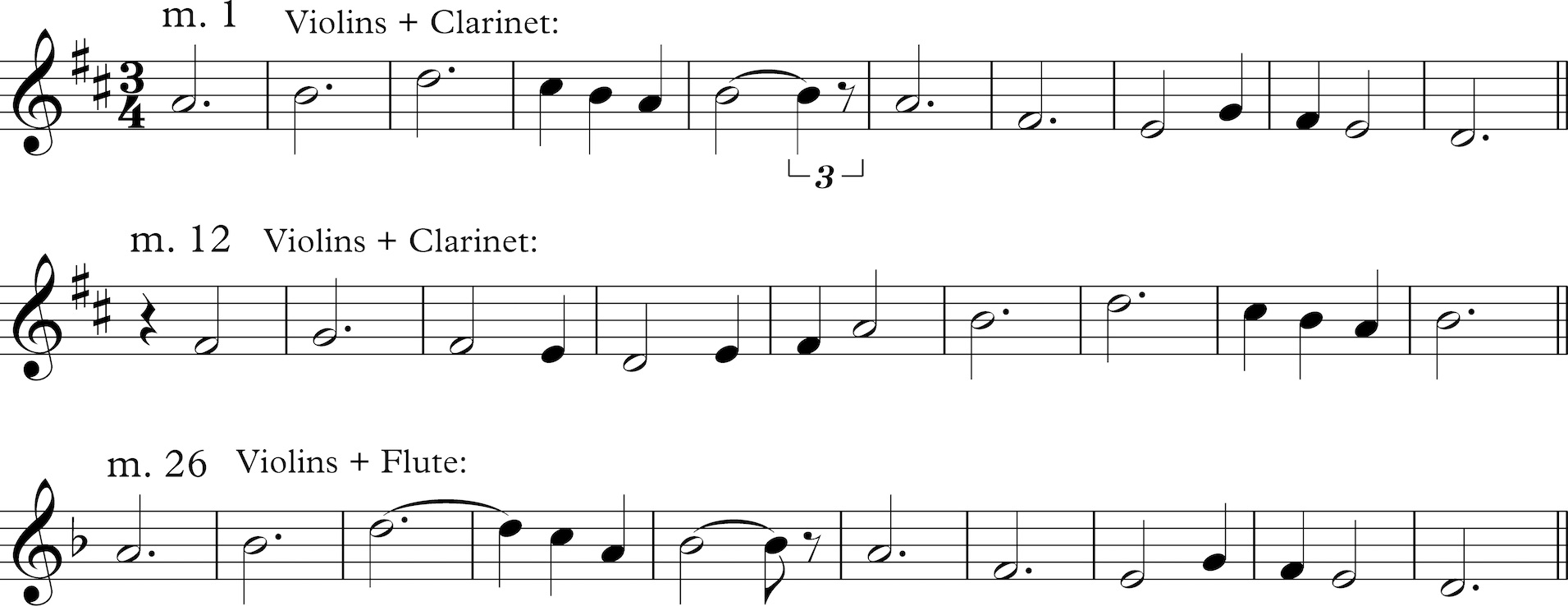

Pastoral melody -- mm. 1-10 -- D major

----Four-note interruption (A) -- m. 11

Pastoral melody -- mm. 12-20

----Four-note interruption (E) -- m. 21

Yes Jesus variation -- mm. 22-25

Pastoral melody -- mm. 26-35 -- D minor

Bitonal maj/min theme -- mm. 36-44 -- D major/minor

Syncopated 3/8 theme -- mm. 45-58 -- F major

Horn/viola duet -- mm. 59-72 -- (C major)

----Four-note interruption (A) -- mm. 73-76

D-maj triads with glissandos -- mm. 77-90 -- D major

----Four-note interruption (A) -- mm. 91-94The second movement, gentle and rather pastoral, contains three themes (in sequence, none repeated after another has entered), one brief variation on "Yes, Jesus Loves Me," a modal and non-thematic duet for horn and viola, and a series of D-major triads approached via glissandoing appaggiaturas - punctuated four times by a series of four repetitions of the same pitch. The first theme I'll call the pastoral theme; it is in an uninflected major scale and accompanied underneath by rolling, mostly scalar lines in the lower strings in triplet eighth-notes, for a 9/8 feel, though with regular eighths and quarters in other parts. Its third instance is basically a repetition in the minor key; the second is like the two halves of the first switched around.

The first phrase is followed by four interruptive A's in the horn, the second by four E's. (It seems odd to just say so, but a notated example would not mitigate the oddness.) Then the oboe and bassoon play a little variation on "Yes, Jesus Loves Me" that might make you notice the pastoral theme's relation to that song.

The final D pivots into the third pastoral melody phrase, now in D minor/F major.

The contrast between D major and minor next seems to surface in an irregular melody played in quasi-octaves, but with the top voice in D minor and the bottom in D major.

That passage leads into one of Thomson's simple scalar tunes in a hemiola-filled 3/8 meter, with enough notes tied over the bar line to render the rhythm ambiguous as it goes along.

This passage segues into a modal duet for viola and horn, with no repetition or perceptible thematic elements.

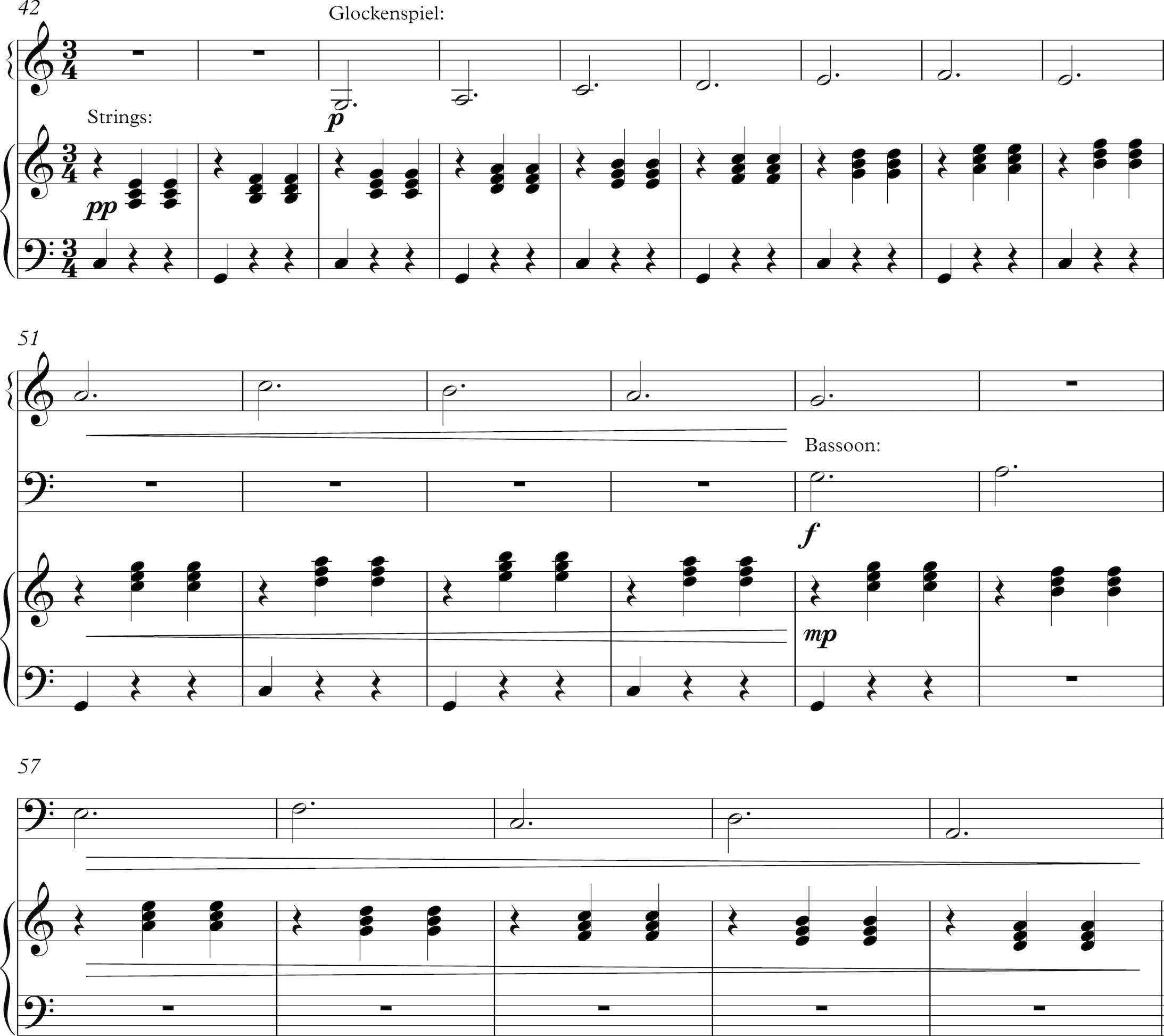

The convergence of these two lines brings us to the third four-note repetition, another loud, decrescendoing A in the horn, this time over a roll on a tam-tam. The remainder of the movement then devolves into an enigmatic stasis. We will now hear fourteen D-major triads in the horns and trombones, most of them approached by glissandos from appoggiaturas below - except notice that the horns slide upward from a C# major triad, while the trombones slide up a whole-step from C and G-natural, so each glissando is also a resolution of a sharp dissonance. Occasionally they pause and a flute plays a high B, the alternation between brass and flute becoming regular at the end.

Has any other symphony ever included a passage of such static, not to say banal, simplicity? Yet it creates its own kind of drama, because we can't quite believe what we're hearing is what we're going to get. And there's also something about the passage that brings the much later music of Morton Feldman to mind, as in the way he repeats sonorities alternating with each other (in Rothko Chapel of 1973, for instance), though with nothing like these homely, smiling triads. And then the winds play our whole-note A's, initiated by string pizzicatos, and the movement is over. We probably ask ourselves: "What just happened?"

Third movement:

Ostinato and simple tune -- mm. 1-31 -- A major

New simple tune -- mm. 32-35

Yes, Jesus Loves Me -- mm. 36-39

Fugue subject -- mm. 40-49

Ostinato with motives -- mm. 50-55

Climax with syncopated theme -- mm. 56-59

Scalar denouement -- mm. 60-64

Chorale with Yes Jesus evocation -- mm. 65-72

Ostinato with Yes Jesus variation -- mm. 73-75

Fifths idea from 1st mvmt. -- mm. 76-78 -- (D major)

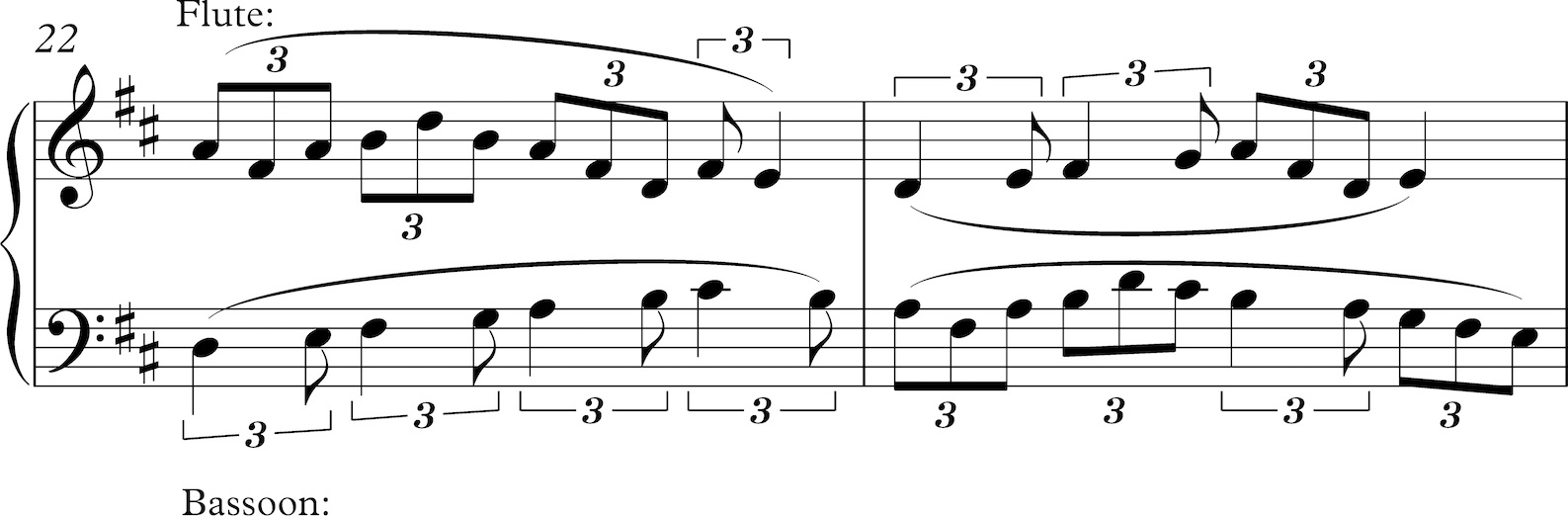

Bb -- mm. 79-81 -- (Bb)Thomson's brief third movement is no scherzo (at least, no more of a joke than the rest of the piece). It starts with a stirring pentatonic ostinato, above which enters one of the simplest of his simple tunes.

The fifteenth iteration of the ostinato is pounded out by the entire orchestra, and the brass break triumphantly into another simple tune.

As though this were the verse of "Jesus Loves Me" (it's not), the entire orchestra responds with a joyous version of "Yes, Jesus loves me!" At its end the cellos and basses break into a long, long fugue subject based on the tune just above. That this is a fugue subject, there can be no doubt; it bears all the hallmarks of the genre - momentum, motivic focus, open-endedness. However, there will be no fugue. No second voice joins in, and at m. 48 the fugue subject, finding no echoing answer, ends by leading back into the ostinato. (If composers could be held accountable for their musical malfeasances, certainly "fugue subject with no intent to fugue" would be an impeachable offense.)

Having been given opportunity to resume, the ostinato returns in crescendo, as the orchestra builds on a A-B-C# motive, finally breaking into a climax at m. 56. This climax is a series of eight punchy chords in a conventional chord progression (I-IV-I-V-vi-iii-IV-I) separated by a quick syncopated figure that jumps among the wind sections. At mm. 60-64 there is a denouement in which various instruments simply climb down an A-major scale from the piccolo to the double basses.

From mm. 65 to 72 the trombones and tuba play a quieter, more thoughtful choral that sounds like a hymn tune but isn't one known to me; above it the piccolo plays a de-rhythmicized, even Ivesian evocation of "Yes, Jesus loves me."

The ostinato returns for two more instances as two trumpets play their own quirkily syncopated version of "Yes, Jesus loves me," and then the horns interrupt with the fifths motive from the beginning of the symphony, now in D. As presumptive cadence, the piccolo, flute, and trombone play an extended Bb over a mysterious snare drum roll.

Fourth movement

First theme -- mm. 1-9 -- A major

Jolly Good Fellow -- mm. 10-23

First theme fragment -- mm. 24-27

Simple tune from mvmt. 2 -- mm. 28-41

Waltz -- mm. 42-69 -- C major

Bitonal theme mvmt. 2 -- mm. 70-74 -- D major/minor

Falling theme -- mm. 75-80 -- (B major)

New theme w Yes Jesus -- mm. 81-88 -- (Eb major)

New theme -- mm. 89-103 -- (F major)

First theme variation -- mm. 104-110 -- A major

Bitonal motive -- mm. 111-115

Syncopated motives JGF -- mm. 116-139

First theme + Foundation -- mm. 140-181

5ths theme from mvmt. 1 -- mm. 182-183

Coda -- mm. 184-198 -- (D major)

--------- Building tension -- mm. 184-191 -- (variable)

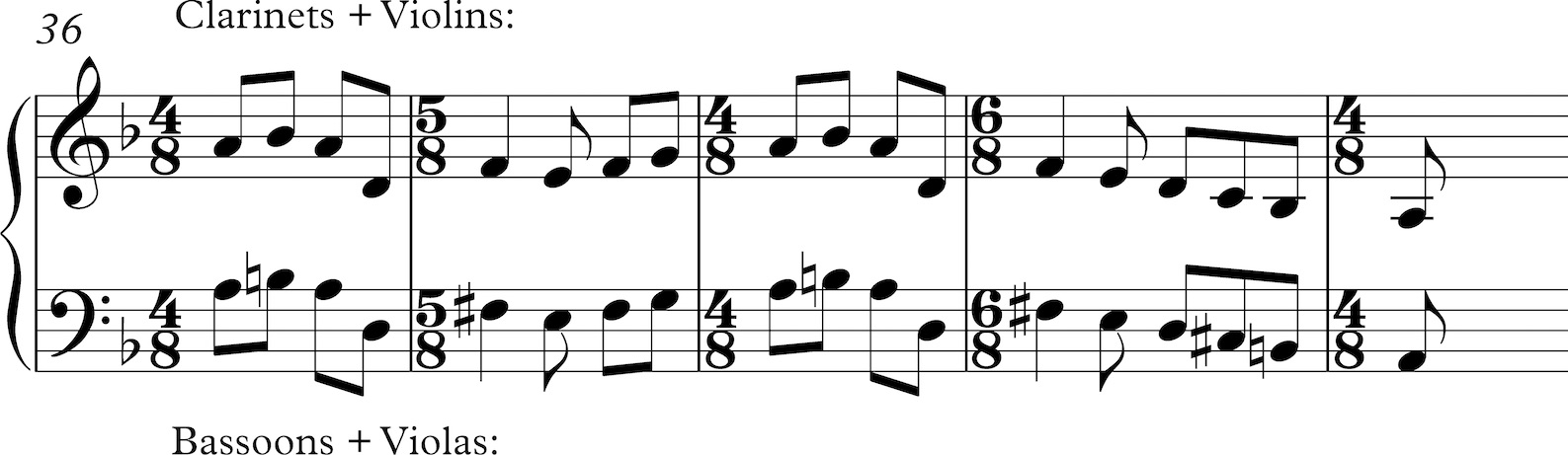

--------- Dissonant chords -- mm. 192-198 -- A majorThe fourth movement, the one Thomson struggled so long to find a form for, brings back enough ideas from previous movements, sometimes simultaneously, as to provide a satisfying culmination to the whole. It is also the most non-repetitive in its thematic material, bringing up a series of new themes used only once and nowhere else. It opens grandly with a theme in unison strings and brass based on "Foundation."

This segues into a kind of jazz version of "For He's a Jolly Good Fellow" whose final phrase, departing from the tune, spirals downward through the orchestra by thirds until its sequence reaches a tonic chord again.

An abbreviated form of the first theme leads back to the syncopated 3/8 meter from the second movement, now notated in 3/4. Next follows a curiously discursive waltz passage, with an aimless tune transferred from the glockenspiel to the bassoon, and then a kind of cadential figure in the brass.

The second movement's bitonal theme in major and minor at once returns at mm. 70-74, leading to an A-natural in the horn echoed by Ab-major chords in the trombones, and then a brief falling theme comes down the scale in thirds. "Yes, Jesus Loves Me" returns at m. 81, accompanying a new and comforting theme in the strings.

This is followed immediately by a grand and similarly homespun new tune.

The subsequent passage, from mm. 104-139, is a passage of free and varied thematic material, starting with an altered version of the first theme leading to a reminiscence of the second movement's major-minor bitonal theme. From here the winds and strings go through a series of scale and syncopated motives that refers to the spiraling ending of "For He's a Jolly Good Fellow," but otherwise defying analysis. At mm. 137-138 the scales lead upward to a climax on A-major and E dominant at once, as preparation for the movement's culminating sequence. An introduction based on the first theme sets the stage for the full-bodied statement of "How Firm a Foundation" that finally arrives at m. 148, accompanied by both the third-movement ostinato and the simple theme that entered above that ostinato at the opening of the third movement.

The hymn's third phrase features the same bitonal dissonance in the bass as was heard at its first statement in the first movement, and the last phrase is joyously concluded with "Yes Jesus Loves Me."

After this thrilling summation, the rest is coda. Brass and strings together bring back the fifths melody from the beginning of the symphony, and then a scale rips upward through the orchestra, changing keys as it goes and sustaining a chord in fourths. The first three chords of the hymn are heard slowly as dissonant notes Bb, D, and F are added to the A-major chord. The piece's most dissonant chord, F major in the treble and A-E-B in the bass, is dramatically struck by tutti orchestra nine times before resolving into A-major.

Nine times feels like one too many, a kind of final wry joke on Thomson's part. Interestingly, Aaron Copland's Billy the Kid (written ten years later in 1938) also ends with a figure repeated nine times before the final chord; I have always speculated that he must have written that with Thomson's Symphony in mind, whether as homage, theft, or in solidarity.

As one can see, the Symphony on a Hymn Tune's unity is not linear nor drawn from any overall harmonic plan, but a result of pieces of the collage being brought back time and again (often in the original key), along with the hymn's opening E-F#-A or a 5-4-3 or 1-2-3 motive providing links among themes. Interestingly, the 1st, 3rd, and 4th movements are in A major, the 2nd movement in D major (slow movement in the subdominant being traditional), and the other keys prominent are G major, C major, D minor, and F major, with a couple of moments in B major and Eb major in the middle of the last movement. Non-sequiturs are common, but repetitions inure the listener to changes in the material. It is a joyously chaotic work on the surface, but brought to a satisfying close by the finale's superimposition of themes.

Copyright 2019 Kyle Gann

Return to American Symphonies

Return to the home page